64% migrant workers were quarantined in villages, 9 in 10 didn’t undergo COVID-19 testing

After travelling hundreds of kilometres, braving heat and hunger, migrant workers reached their villages, majority were quarantined. Many centres lacked power, toilets, and food facilities.

Migrant worker at a quarantine centre in Uttar Pradesh's Sitapur district.

Stranded for over two months in Leh-Ladakh due to the COVID-19 lockdown, 25-year-old John Paulus Hansda, a road construction labourer and a resident of Mohaligadpatthar village in Dumka district of Jharkhand was airlifted, along with other workers, by the Jharkhand government on May 29. That was the first time Hansda and his fellow workers had boarded an aircraft. Excitedly they landed in Ranchi, the state capital, and headed for Dumka.

But that was the start of another struggle for Hansda. As soon as he arrived in his village, he headed to a local government school, which had been converted into a quarantine centre for the returnee migrant workers. The migrant workers had to stay in the facility for two weeks before going home and meeting their families.

“We stayed at a school that had no fans or electricity. We would sleep on the terrace and the bedding was provided by our families. The day we came, we had to even clean dirty toilets used by others before we could use them,” Hansda told Gaon Connection.

“There was nothing in the name of facilities at the quarantine centre. We would not even get two proper meals a day. My family used to bring food for me,” he added.

To understand the impact of COVID19 on rural India, including migrant workers, Gaon Connection conducted a national rural survey — the first of its kind in the country. More than 25,371 rural residents were interviewed across 23 states. The survey also had a supplementary questionnaire for migrant workers like Hansda to understand how they coped with the lockdown and the pandemic.

The results of the national survey show almost one-fourth (23 per cent) migrant workers returned home walking during the lockdown, whereas 18 per cent travelled by bus, and 12 per cent by train. While returning home, 12 per cent were beaten by the police. Another 14 per cent informed they were ill-treated by the people, and 67 per cent received no help from the people on their journey back home. A large number of migrant workers were financially broke, and over 40 per cent faced hunger on their journey back home.

The sufferings of migrant workers did not end upon reaching their villages. To curb the spread of coronavirus, the government had advised 14-day quarantine for the returnee migrants. According to the Union ministry of health & family welfare, basic infrastructure/functional requirements at a quarantine facility included lighting, well-ventilation, electricity, ceiling fan, potable water, food, snacks, recreation areas including television, sanitation services/cleaning and housekeeping.

However, much of these were missing at the quarantine centres set up in the rural pockets.

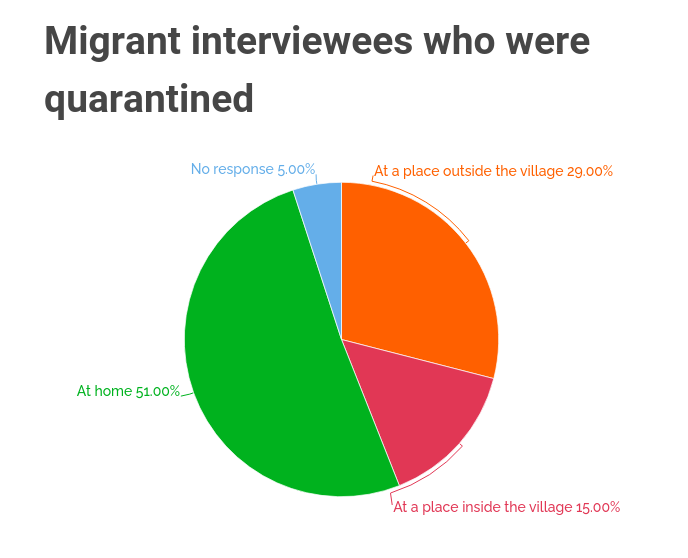

The recent Gaon Connection Survey found 64 per cent migrant workers were quarantined upon returning to their home states/districts. Half of these underwent home quarantine, whereas the other half were kept in schools and other institutes converted into quarantine facilities.

Gaon Connection spoke with migrant workers who narrated how they were forced to sleep in the heat of April-June without ceilings fans, defecate in open or filthy toilets without handwash or soap, or sleep without mosquito nets or bedding. Some could not even receive two proper meals a day at these quarantine centres.

Dilip Mehto hails from Kothi village in Bokaro district of Jharkhand, and used to work as a driver in Mumbai. Upon returning to his state during the lockdown, he had a rough experience staying at the quarantine facility.

“The anganwadi [rural child-care centre] where I was put up for 10 days didn’t even have a toilet. We would defecate in the open and bathe in the nearby river. Not only men, but many women in the school too had to defecate in the open,” Mehto told Gaon Connection. .

But, he still considered himself fortunate, as “my wife used to bring drinking water and hot food for me. If we didn’t have ration at home, we would go hungry at these centres,” he said.

Meanwhile, many migrant workers didn’t even get a proper shelter for quarantine purpose. Over 29 per cent migrant worker respondents said they were kept outside the village, at the mercy of weather.

Take the case of Bablu Chaurasia, a resident of Manglupur village in Gonda district of Uttar Pradesh, who used to work in Punjab. “I returned from Punjab to my village and was asked to live in an open field for 20 days. Nobody came to check on me while I was there,” he narrated to Gaon Connection.

Interestingly, over half the migrant workers, 51 per cent, were quarantined at home, found the Gaon Connection Survey.

“When I came back from Ludhiana in Punjab, the pradhan [village head] suggested I undergo home quarantine,” Mahendra Dewasi, a resident of Jaitaran village in Pali district of Rajasthan told Gaon Connection.

“We were told quarantine centres would be set up in schools, but that did not happen, hence migrant workers were suggested to follow home quarantine,” informed Pradeep Khoja, another resident of Pali district.

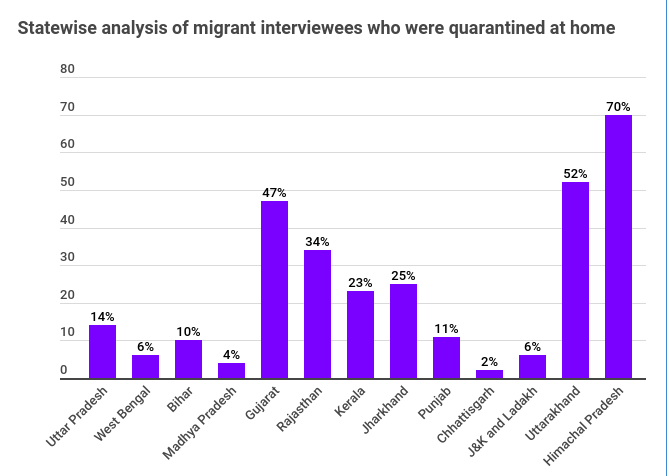

The survey data shows 34 per cent migrant workers were home quarantined in Rajasthan.

Home quarantine had its own challenges. Most villagers do not have more than one or two rooms in their homes. “Upon returning to my village, I tested negative for coronavirus, so after spending three days at an institutional quarantine facility, the village authorities told me to follow home quarantine. But, there is no separate room in my house, so I was forced to live with my family,” said Shyamal Pramanik, a resident of Bardhaman in West Bengal.

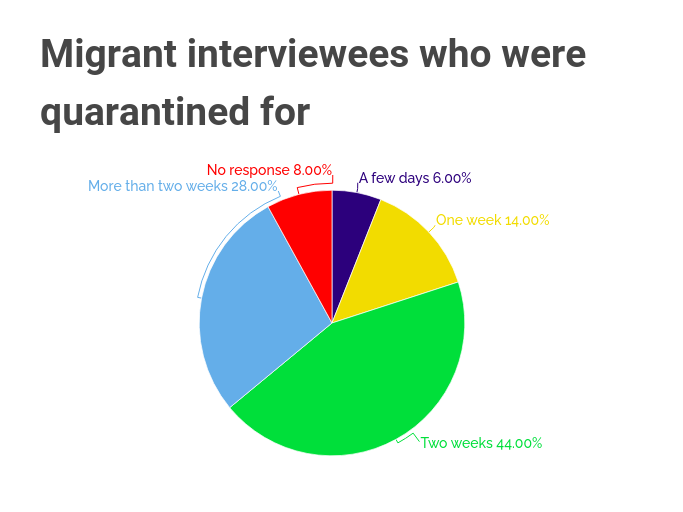

As part of the survey, migrant workers were asked the number of days they spent at home, or institutional facility for quarantine. The results show around six per cent were kept at a quarantine facility for a few days, while 14 per cent for one week, 44 per cent two weeks, and around 28 per cent more than two weeks.

Upon returning home, these migrant workers also faced food shortage. Some complained they were not even checked for coronavirus. “I did not receive any facility from our gram panchayat after returning home. I have neither received ration nor anything else,” Lakhan Lal, a resident of Dhikpur in Chhatarpur district of Madhya Pradesh told Gaon Connection. “I used to work in Himachal Pradesh. No check-up was done when I returned to the village,” he added.

Interestingly, 88 per cent respondents of Gaon Connection Survey claimed they didn’t undergo any tests for COVID-19. Majority said they only underwent thermal screening.

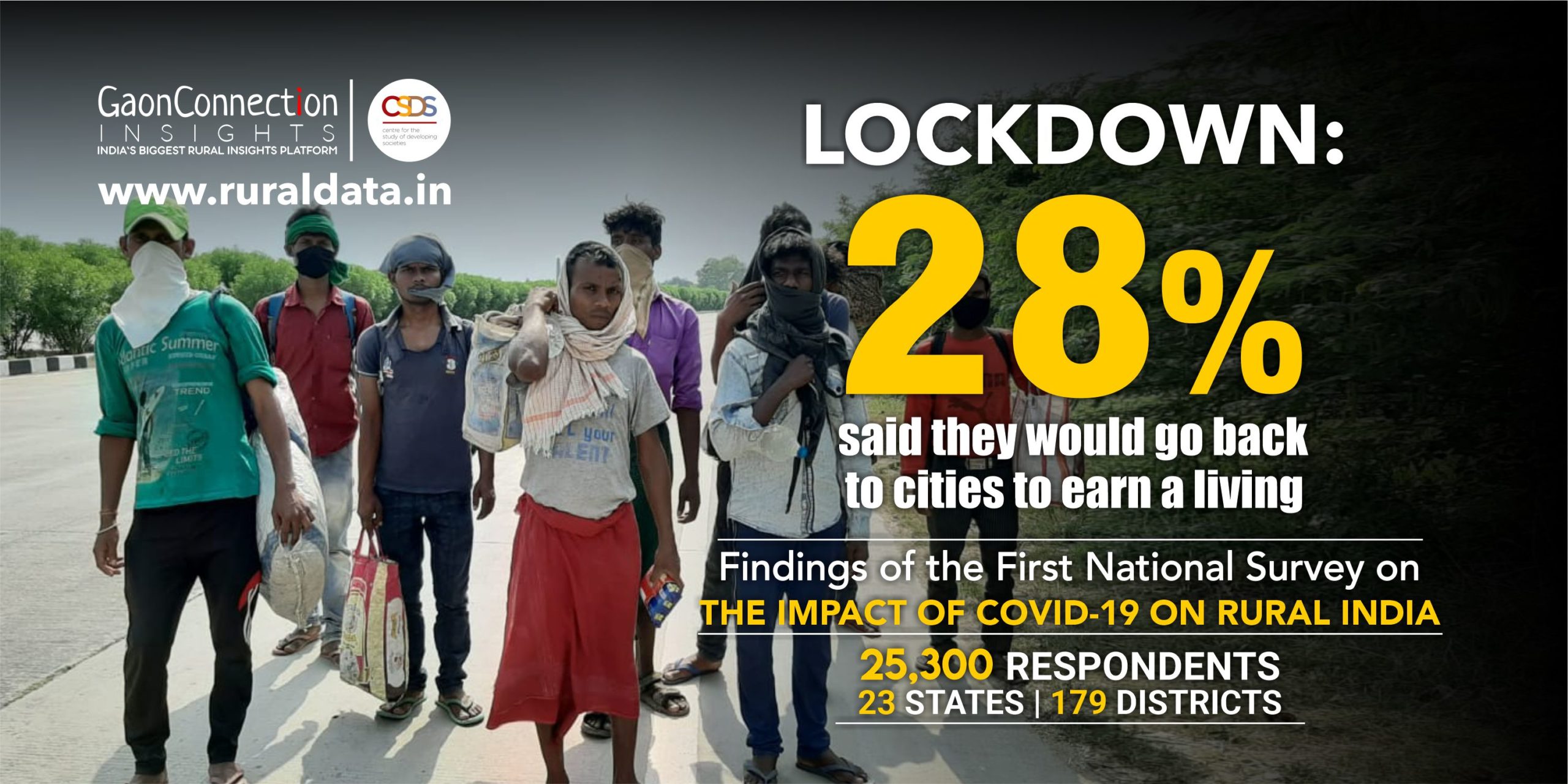

In spite of a painful homecoming, 28% per cent migrant workers said they wanted to go back to the cities to work. Meanwhile, 26 per cent said they would stay back in their village homes. Of those staying back, 37 per cent planned to do farming and 24 per cent labour jobs.

While Mehto, a resident of Bokaro, Jharkhand, has gone back to Mumbai to provide for his family, Hansda has stayed back in Dumka to farm his fields.