92% rural poor households faced difficulty in accessing food during the lockdown: Gaon Connection Survey

Millions of migrant workers returned to their villages after they lost their jobs during the lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Many were afraid of the contagion but most returned as they feared dying of starvation as they had run out of money to buy food.

Upendra Manjhi, a migrant worker from Raath in Hamirpur district of Uttar Pradesh worked in a denim labling company in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, till his company shut down as soon as the coronavirus enforced lockdown began, leaving him with no money to buy food.

“The work stopped as soon as the lockdown began in March and so did my salary. When we had no more money to buy food, I managed to return to my village with my wife and two kids,” Manjhi told Gaon Connection.

“I don’t know about coronavirus but had I not returned to the village, my entire family would have definitely died of hunger in the city. Thus, coming to the village saved us all from death,” Manjhi said.

The country’s largest rural media institution, Gaon Connection, conducted a survey among more than 25,000 villagers in 179 districts of 20 states and three union territories across the country to take stock of the situation arising out of the COVID-19 lockdown. The survey was done between May 30 and July 16, 2020 under which 25,371 people had participated. In this survey, the villagers shared the difficulties arising out of the lockdown with Gaon Connection.

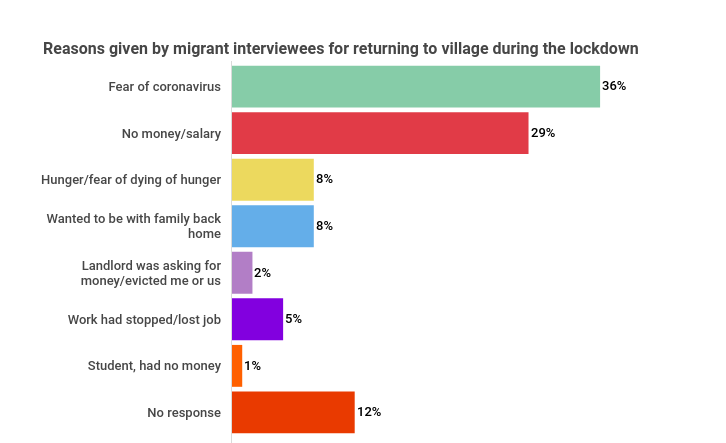

Of the 963 migrant workers involved in the survey, 36 per cent respondents said they feared the contagion the most while they were in the city during the lockdown, while 29 per cent said they returned to their villages due to economic reasons. Of these, eight per cent said they had feared starvation whereas eight per cent of the people said they wanted to be with their families in such difficult times. While five per cent had returned due to loss of livelihood, two per cent returned as they could not pay rent for their accommodation.

Virendra Singh of Neusa village under Maman panchayat in Umaria district of Madhya Pradesh worked in a saria (steel rods) company at Jalan in Aurangabad. “My company closed down and I managed to stay for a month after which I ran out of money. I lived on food offered by others but that too stopped. With no food or money, I, along with many others, returned home. We at least get some foodgrains here and I have found some work to do too,” he told Gaon Connection. “Although we were afraid of coronavirus, we were more worried of getting food with no money. At least here in the village, we will not go hungry,” he added.

COVID19 lockdown caused the second largest reverse migration after independence in the country wherein more than one crore people returned to their villages from metros like Delhi, Mumbai, Surat and Chennai.

During the lockdown, the country’s chief labour commissioner said about 26 lakh migrant labourers had returned home. The solicitor general of the Government of India said 97 lakh migrants had returned while researchers studying reverse migration put the number at 2-2.2 crore migrants.

Rajesh Pandey from Satna district of Madhya Pradesh worked in a textile company in Mumbai, before it closed down during the lockdown. “The threat of coronavirus was very high where we lived. There were several cases in our building and the medical facilities were poor. With no job or money I returned home when I couldn’t buy food anymore,” Pandey said.

The Gaon Connection survey found that inability to buy food was a major reason for the migrants returning to their villages.

Of the 963 returnees surveyed, 17 per cent said they often could not buy either roti (chapati) or vegetables during the lockdown, 22 per cent said they sometimes had to cutback on regular food items, 20 per cent of the respondents said their diet was not majorly affected whereas 28 per cent said the lockdown did not affect their diet, and 13 per cent of the people did not respond.

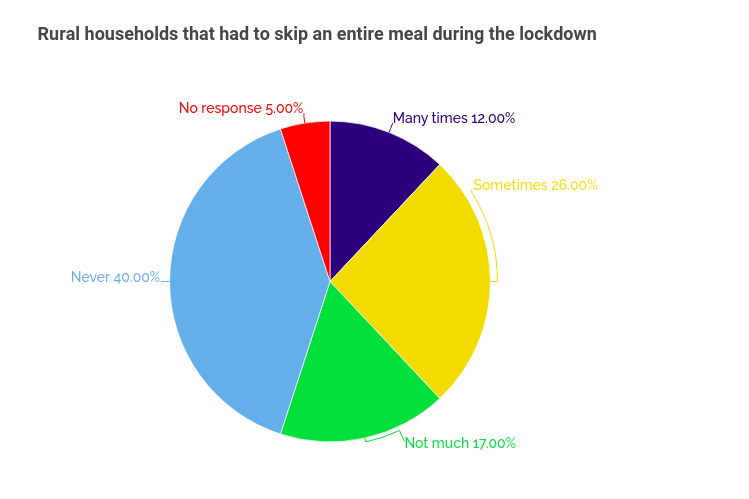

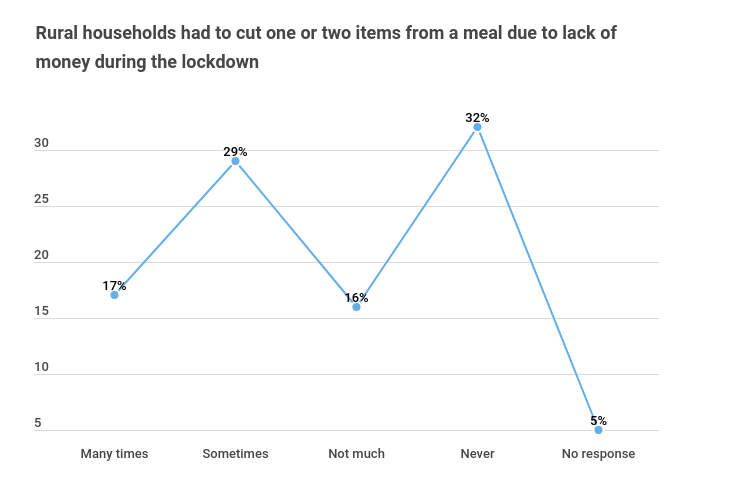

Many of those surveyed said often they had to go to bed hungry during the lockdown. Sixteen per cent said they ate only once a day while 25 per cent of the people had to occasionally go hungry, 15 per cent suffered no major shortage of food whereas 31 per cent said they never had to skip a full meal during the lockdown.

The survey had many other startling findings. Thirteen per cent of the people said they had frequently gone hungry the whole day while they remained in the city during the lockdown. Twenty-three per cent of the respondents said they sometimes went hungry for the entire day while 15 per cent said this had rarely happened, 35 per cent had not starved for a single day whereas 13 per cent did not respond.

Noor Alam, a resident of Araria district of Bihar, stitched ladies garments in Jaipur and was forced to return home in May. “My company did not pay me for about 25 days of work. I earned about Rs 7,000- 8,000 a month, of which I had to send some money home. So when the company stopped its payment, I was not left with enough money to buy food,” he said.

“For many days, some people would distribute food but that too stopped. At times I survived on biscuits all day. I had no money to buy food and I realised that if I did not return to my village I would die of starvation,” Alam told Gaon connection over phone.

Another issue faced by the migrant workers in the city was accessing medical treatment and essential medicines during the lockdown. Many could not step out to buy medicines because of police presence, they said.

Fifteen per cent of the people said they could not get the necessary medicines or treatment, the survey said while 22 per cent faced this problem for a limited duration. Fourteen per cent hadn’t faced major problems. Thirty-six per cent of the people said they did not face any problem in finding medicines while 13 per cent did not respond.

Pervez of Jharkhand’s capital Ranchi was stranded in Ahmedabad in Gujarat during the lockdown and had posted a video appealing for help. Both his kidneys were damaged and he later died for want of proper treatment.

Pervez’s elder brother Tauheed Ansari told Gaon Connection over phone that his brother had called him in March and told him about his illness and that he had nothing to eat and had no money. “I sent Rs 1,200 to his account but he could not withdraw it. Thereafter, the lockdown was imposed and he could not be treated nor could be eat well. We were so far away from him, how could we have reached him?” Ansari asked.

Neeraj Kumar of Bhadohi district in Uttar Pradesh faced health issues while working in Mumbai where he repaired electronic items. “I had a problem with my throat and liver. I had consulted a doctor just before the lockdown. The clinic remained shut during the lockdown and I could not buy more medicines as the government hospitals had become centres for corona testing. I returned to my village and resumed treatment with the help of a local doctor,” Kumar told Gaon Connection.

Among migrant workers living in the cities, the survey found that getting food was a big issue for those whose monthly income was low. The survey said 34 per cent of those with monthly income of up to Rs 5,000 had to go without some food items several times. Thirty-three per cent of the people quite often managed to get only one meal a day and 25 per cent had to frequently go without food the whole day, 32 per cent of the people who needed medicine and treatment could not get it.

The situation of people earning Rs 5,000-10,000 a month was slightly better. Among those earning within this range, 20 per cent had to many times reduce some food items in their diet while 19 per cent of the people ate one meal a day on most days, 17 per cent of the people went without food all day, while 16 per cent could not get medical treatment or medicine due to lockdown.

Those earning more than Rs 10,000 a month fared better with 10 per cent of the people skipping some food items from their diet while eight per cent had to sometimes have one meal a single a day. Four per cent said they had to go without food many times, while one per cent said they could not get medicine and treatment, the survey said.