A library for rice with grains from the past

An Assamese farmer, Mahan Chandra Borah, has set up northeast India’s first seed library in Jorhat, called Annapoorna, to revive indigenous, sustainable and nutritious rice varieties.

Mahan Borah, a rice farmer, set up northeast India’s first seed library with over 300 varieties of indigenous rice. Photo: Mahan Borah

Thirty-eight-year-old Mahan Chandra Borah, a resident of Meleng in the Jorhat district of upper Assam, about 315 kilometers from the state capital of Guwahati, belongs to the rice farming community of Assam. But, he is more than a rice farmer. He is also a ‘librarian’ who has set up northeast India’s first seed library with over 300 varieties of indigenous rice. On half an acre of his approximately three and a half acre of farmland, he is experimenting with growing indigenous rice too.

It was fourteen years ago that Borah dreamt of doing something beyond cultivating paddy. The history graduate wanted to set up a library to benefit his rice farming community. And, not a regular library, but a library of varieties of indigenous seeds, which he feared would be lost forever. “I started visiting farmers in the vicinity, collected seeds they used for sowing, learnt of other farmers who sowed other kinds of rice, and in this way managed to collect a good variety of rice seeds,” he told Gaon Connection.

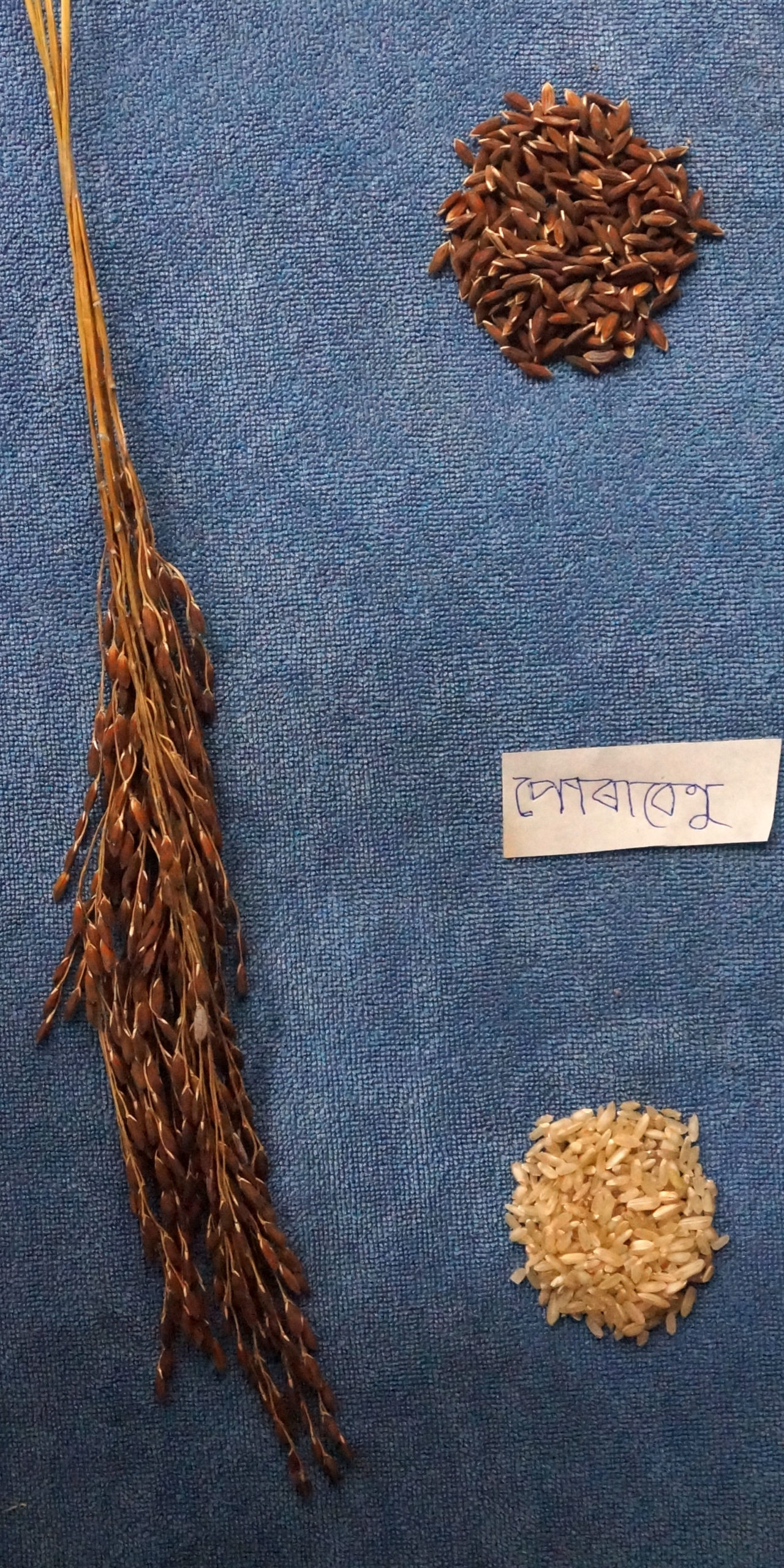

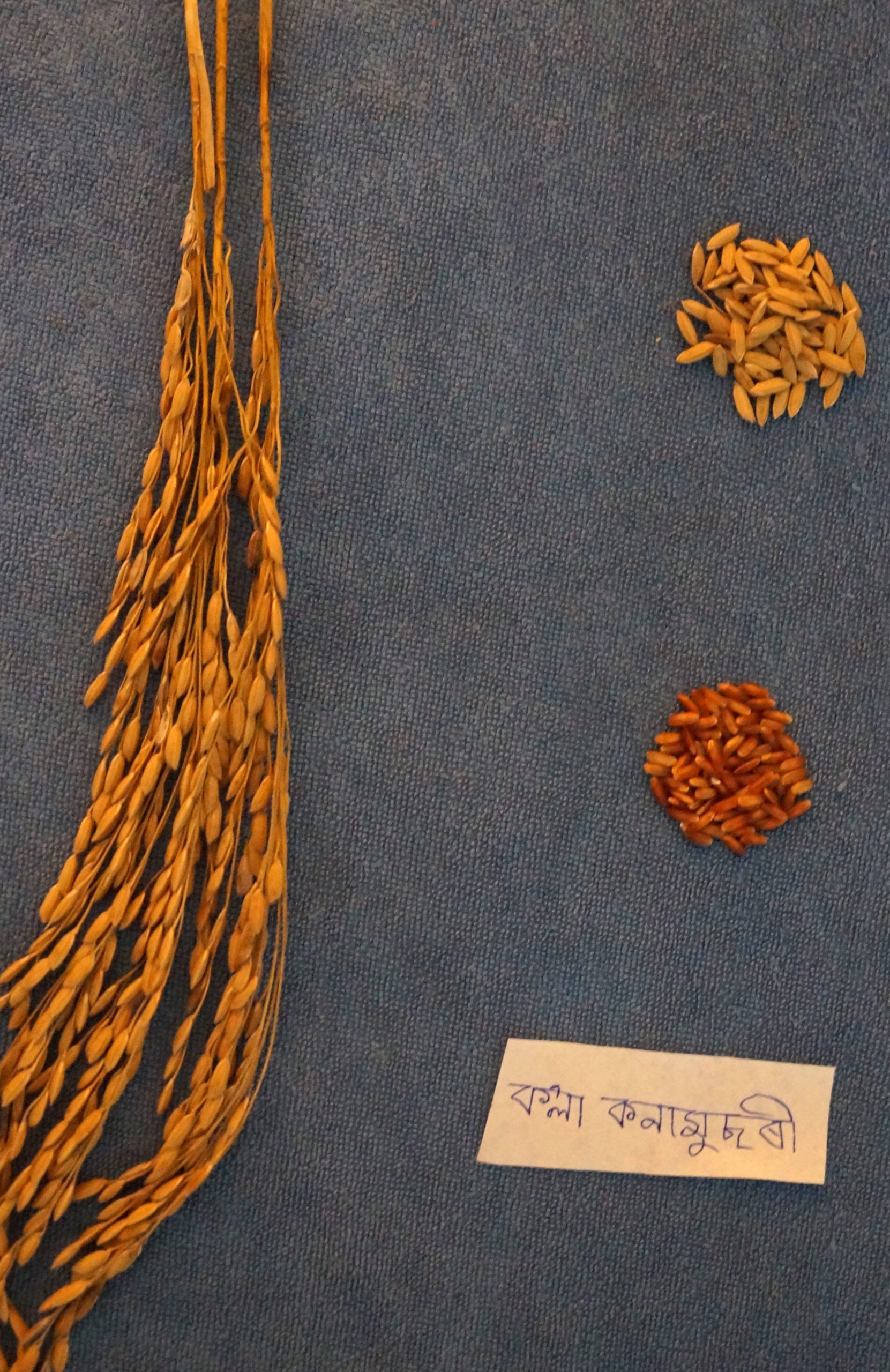

Today, Borah has northeast India’s first seed library with 300 indigenous varieties of rice. Named Annapurna, the library, set up in his house, is a gene bank of indigenous seeds that are fast disappearing, not only from Assam, but from other parts of northeast India and the rest of the country as well. From just three varieties collected from neighbouring farmers, Borah fanned out to a wider radius of farmlands and farmers, and gathered other seed varieties that include aromatic, sticky, black, flood-tolerant and hill rice, some of them with medicinal properties.

Fever rice, floods rice

Talking about the variety of rice in Assam and other parts of the country, Borah said: “The Dol kosu variety of Assam is known to have a cooling effect on the body and was once consumed when people suffered from fever.” Similarly, Navara, a rice variety from Kerala, was used in Ayurvedic medicines, he said. Seeds of both these varieties are saved in his library.

Another variety close to Borah’s heart is the Bao dhan that adapts well to the climatic conditions of the flood-prone state of Assam and can withstand long periods of being submerged in inundated fields. Despite its flood-resilient properties, this rice slowly started losing its popularity to the higher-yielding hybrid varieties.

“Bao Dhan is naturally adapted to flood-prone Assam’s climate, and is highly nutritious. This rice is marketed as red rice because of its colour,” Pallav Kumar Sarma, chief scientist at the Biswanath College of Agriculture, Sonitpur Assam, told Gaon Connection. Like most indigenous rice varieties, Bao Dhan is a low yield variety with an output of about 1.5 to 2 tonnes per hectare. In contrast, high-yielding varieties of rice which have become popular with farmers, give about 4-5 tonnes per hectare.

“However, flood-prone areas like the Majuli river island and the Lakhimpur district continue to grow Bao dhan,” said Borah. A number of other farmers are now joining this list, he added.

According to the Rice Knowledge Bank, rice occupies 2.54 million hectares (over 61 per cent) of the gross cropped area of 4.16 million hectares in Assam and contributes 96 per cent of the total food grain production in the state.

In his seed library, Borah has managed to save 25 varieties of Bao dhan, each one different in colour, size, and characteristics. Ranga Bao, for example, is highly tolerant to flood water, compared to Maguri. Other flood-resilient varieties include Betu, Deori Bao and Amona Bao, all of which are there in the library.

Some varieties of rice that Borah had collected from farmers, like the Xuadhmoni dhani, three or four years ago, cannot be found in that area anymore. He had anticipated this when he began his seed collection initiative 14 years ago. It was a time when hybrid varieties had made an appearance and farmers were opting for them because of their higher yield instead of the local varieties.

“Increasing population and the corollary increase in hunger has meant a rise in high-yielding varieties instead of traditional ones,” T Ahmed, chief scientist at the Regional Agricultural Research Station in Titabar, Assam, told Gaon Connection. At the two research stations of the Assam Agriculture University, they have the germplasm of more than 4,500 indigenous rice varieties that are carefully cultivated every year.

“It is important to save these varieties because they have intrinsic properties like the ability to survive floods or diseases that have been evolving over hundreds of years,” reiterated Ahmed. “Despite low yields, there are some advantages of traditional varieties, he added. “Like their resistance to pests in comparison to high-yielding varieties that are also very time sensitive. Traditional varieties are more adaptable and therefore a valuable asset,” he said.

Planting seeds of change

Borah’s 14-year journey from a rice farmer to a rice seed librarian has not been easy. Initially, he approached different non-profit organisations to work on the idea of creating such a library. But no one showed interest saying there were no funds. So he decided to do everything on his own.

An important aspect of Borah’s seed library is that it also functions as a practical laboratory where the rice seeds are planted and harvested every year. “Only when you plant these seeds every year, will they adapt to the changing climatic conditions. The gene makeup will remain the same,” he explained to Gaon Connection.

So, each year, depending on the rice, and whether it is a winter, autumn, summer or Bao variety, he sows the seeds on neatly demarcated portions of four by four feet. The seeds of these plants are then collected and deposited in the library.

“Earlier, it wasn’t uncommon to have 10-12 varieties of rice seeds in one place. Now, the varieties have come down to just four or five. Seed diversity has therefore decreased,” lamented Borah who often gives seeds to other farmers who come to him asking for indigenous rice varieties. He gives away his rice seeds for free.

The Annapurna Seed Library is also the sister library of California-based Richmond Grows Seed Library.

Diversity, sustainability and food security

For Borah, preserving indigenous seeds is also about preserving the culture of Assam. “Agriculture is our culture and food is an important part of that for us. Our ancestors grew a wide variety of rice with each kind having its own specific qualities. If that diversity is lost, what will our grandchildren remember of the rich past?” he asked.

Food diversity is food security, believe the rice activists and scientists, and that is why it is of paramount importance to preserve the indigenous varieties of rice for posterity.