Aadhaar-induced exclusion from the PDS is making poor go hungry in Odisha; universalise PDS, demand activists

It is estimated the mandatory linking of Aadhaar with ration cards has excluded about 1.9 million people in the eastern state. Although the state government has promised ration for all in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, several poor households are going without food.

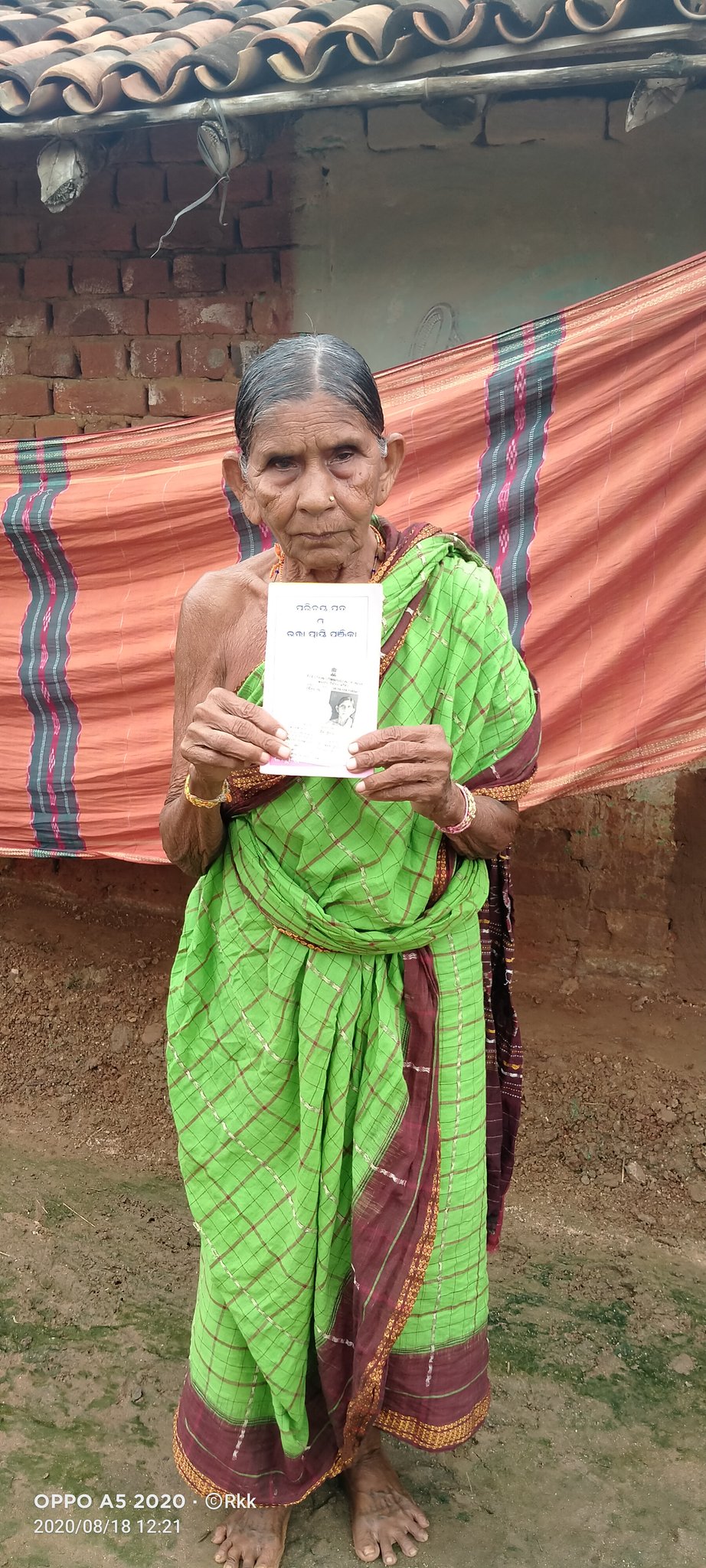

Mati Talia, widow, who lives in Badaguda village, Kaoraput, Odisha, has applied for Aadhaar many times. She didn't get ration card or pension. Photo: Right to Food Campaign, Odisha

Padmanabha Patra, a 36-year-old migrant worker from Kasada village in Sundergarh district of Odisha, used to do odd jobs as a daily wager in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, over 1,400-kilometre from his home, to make both the ends meet. During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, when the nationwide lockdown was enforced, he had no work to do in Chennai and soon ran out of money.

He was desperate to return home. After great difficulty, he, along with nine other migrant workers, found a private local transport from Chennai to Odisha, for which each of the workers paid Rs 6,000 and returned home.

However, his woes did not end. He has been unable to access his share of ration from the local fair price shop under the Indian government’s public distribution system (PDS). Every time he visits the ration shop, he is turned away saying his Aadhaar is not linked with his ration card. He has failed to get his entitlement under the PDS for the last few months now.

“I do not understand why everyone keeps saying I won’t get my ration entitlements because of Aadhaar related issue. In this pandemic, how do I get it fixed so that I can get food to eat?” he asked Gaon Connection.

Without Padmanabha’s share of ration entitlements, his family is falling short of food. “Ration entitlements for three people can’t feed the four of us. More so when we do not have a stable source of income due to the coronavirus,” said Lakhmana Patra, his brother.

Padmanabha is not an isolated case of villagers in Odisha unable to access their PDS entitlements. His neighbour, Subham Kumar Patta, is also trying to fix the Aadhaar and ration card linking issue.

Last year on September 15, the Odisha government’s Food Supply and Consumer Welfare Department made linking of Aadhaar numbers with ration cards mandatory because of which, it was expected, about 1.9 million people would be excluded from the PDS. These people either do not have an Aadhaar card, or have not linked it with their ration cards. A large chunk of such population is suffering food scarcity.

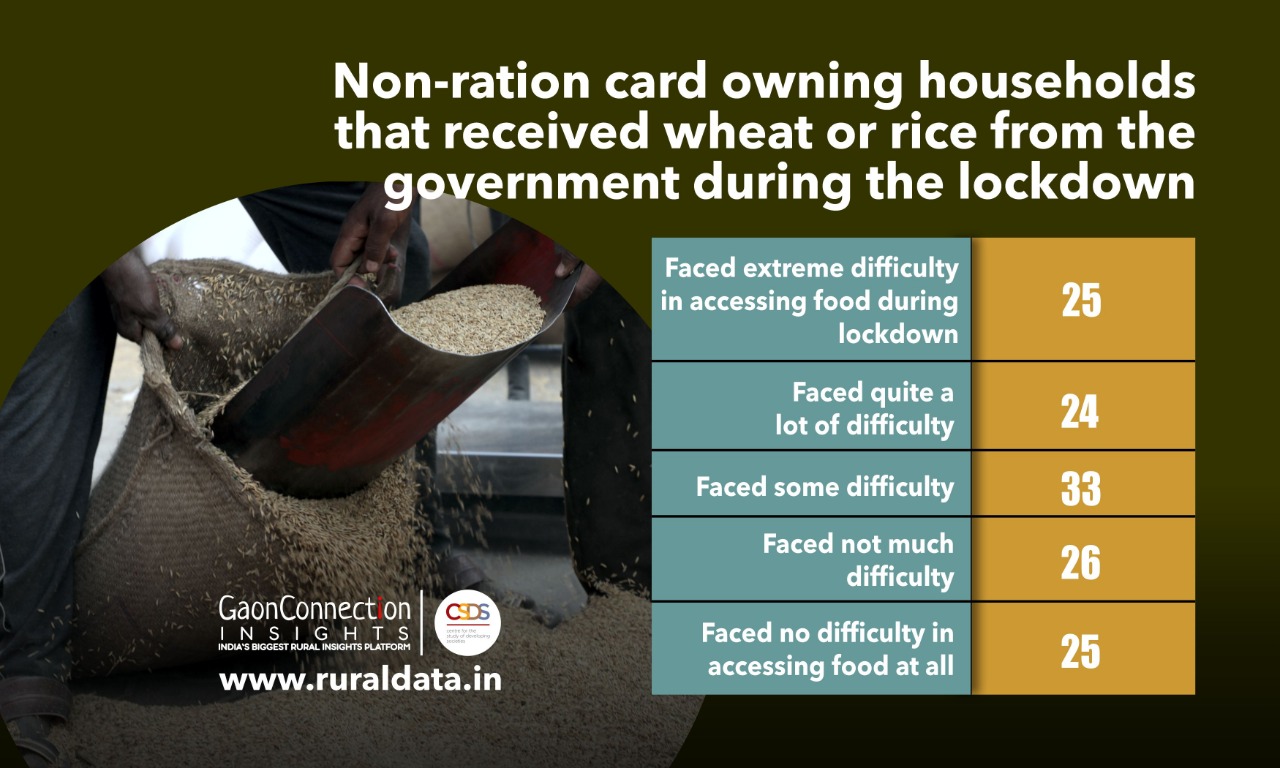

Padmanabha’s case echoes the findings of the recent Gaon Connection national rural survey on the impact of COVID19 on rural India. It found a majority of the economically poor rural households with no ration card faced ‘very high’ or ‘high’ difficulty in accessing food during the lockdown, as they failed to receive the government ration.

Further, the survey found, three-fourth poor households without ration card didn’t receive government ration in lockdown. And, seven in 10 economically weak households with no ration cards reportedly faced ‘very high’ or ‘high’ difficulty in accessing food during the lockdown. This national survey covered 25,300 respondents in 179 districts across 20 states and three union territories, and was conducted by Gaon Connection Insights, the data and insight arm of India’s largest rural media platform.

The beneficiaries of PDS claim they have been unable to fix the Aadhaar issue in spite of several attempts. For instance, earlier this year, in February, Padmanabha’s brother, Lakhmana and his neighbour Patta, travelled 25 kilometres to visit the Seva Kendra at the Bonai block office to fix the Aadhaar-ration card linking problem. After waiting a couple of hours, by the time their turn came, the official at the counter informed them it was lunch time and they should come back later. Later when they visited the Seva Kendra again, other excuses cropped up.

On the one hand rural poor are unable to access ration, on the other hand, hunger deaths are being reported in the state. The eastern India state reported its first case of starvation death during the lockdown on June 24 when Dukhi Jani, a 46-year-old destitute tribal woman in Kaliamba village of Nayagarh district succumbed to death after going without food for three days.

Early next month, on July 3 when the members of Odisha Right to Food campaign reached her village for fact-finding, they found Jani had received no support from pension, MGNREGA [Mahatma Gandhi national Rural Employment Guarantee Act], or the Jan Dhan Yojana. Despite meeting all the eligibility criteria, she did not have an Antodaya Anna Yojana card.

However, she did have an Annapurna card, a ration card sanctioned in March 2016 that entitled her to get 10 kilos of rice per month from the PDS. But, had not received any ration for more than a year (15 months). Padmalochan Biswal, the Jakeda panchayat executive officer, told the fact-finding team it was likely Jani’s Annapurna card was cancelled due to non-seeding of Aadhaar number with her ration card.

The Odisha Right To Food campaign has been repeatedly highlighting the perils of linking Aadhaar to PDS because of which poor families are being deprived of their rightful share of ration. Between July 1 and July 15 this year, its members conducted a survey in 10 migration-prone blocks in Bargarh, Balangir, Kalahandi and Nuapada districts of the state.

They found almost 57 per cent of the households were worried about not having enough food and cash to survive. Also, 54 per cent of the surveyed households had already been eating fewer meals. Over 10 per cent of these households reported one or more members of their families had been excluded from the PDS due to Aadhaar or seeding issue. Hence, they had been losing out on their five kilos rice entitlement per person per month.

But, the authorities seem unfazed. Earlier this month, in an interview, Ranendra Pratap Swain, the state minister for Food Supplies & Consumer Welfare, called starvation deaths “a thing of the past.” He claimed no Aadhaar related PDS exclusions have happened in Odisha, and that the authorities had taken a “liberal” view during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, he went on to advocate linking of Aadhaar and PDS services to weed out corruption and duplication.

The Odisha Right To Food campaign wrote to the state food commission flagging serious concerns about the proposal and even met Swain. “He clearly said depriving any beneficiary of their ration entitlements because of Aadhaar issue was absolutely criminal and promised to set up a meeting with the food secretary to discuss the next course of action. But, we have not heard back from him,” Sameet Panda, member of the Odisha Right To Food campaign told Gaon Connection. The bureaucrats keep speaking about Aadhaar tackling the issue of bogus ration cards, but they have no details whatsoever on the number and kind of such bogus cards in the state, he added.

Last month, on July 18, Swain tweeted that Aadhaar based biometric authentication using ePOS machines (Electronic Point of Sale digital system) at fair price shops for PDS will be discontinued indefinitely in view of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was a much needed and widely appreciated move by the state government. Panda has filed an RTI to find out if 1.9 million excluded from the PDS due to Aadhaar issues have been receiving ration in the pandemic or not. He is awaiting its reply.

Amid the pandemic, the state food ministry seems extremely responsive to grievances raised on social media. For instance, when the case of Fuleshwari’s family not being able to receive any rations for the lack of ration cards was reported, Swain promptly asked for her details and initiated corrective action. In a few days, she was given a ration card, her ration entitlements, as well as her cash relief.

But, is that enough?

“The government excluded millions of people from their ration entitlements with a single broad stroke decision, and now it is taking credit for taking action on, say, five exclusions highlighted on social media per day. This is definitely not acceptable,” Rajkishor Mishra, director of Rupayaan, a non-profit working in Odisha with the poor and excluded communities, told Gaon Connection. He is also the former state advisor to the Supreme Court Commissioners on the Right to Food.

As if the Aadhaar woes for ration and PDS were not enough, the state government had recently decided to restrict pension payments to ‘Aadhaar verified’ accounts only. This move was expected to exclude more than 1.1 million beneficiaries. The Odisha Right To Food campaign called for a roll-back of the order.

Two days back, on August 27, the state government made a quick U-turn on this decision. Bhaskar Sarma, secretary, Social Security & Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities Department of the state government shot off a letter to the collectors stating pension beneficiaries will not be excluded for Aadhaar. He has directed the local administration to help people get their Aadhaar cards made for the next round of pension disbursement.

According to Mishra, the solution to the ‘exclusion’ lies not in these piecemeal measures by the government, but a proper universalisation of the PDS, which means ration for all the needy people. “We did have universal PDS in the Kalahandi–Balnagir–Koraput region of the state from 2008 to 2015. But, not anymore.” he said.

Meanwhile, both Padmanabha and his brother Lakhmana are working in the fields in their village to feed their families. “It is hard to survive like this. When can I get my share of ration from the shop?” wondered Padmanabha.