Baoris, Bijli Swaraj and Biomass Plants: How the states are responding to climate change

From reviving water bodies to carbon neutral villages and gram panchayats, several states in India are responding to climate change. But is that enough?

Although COVID-19 remains an immediate danger, action on climate change cannot be delayed. Photo: Nidhi Jamwal

During the recent US election presidential debate, Donald Trump called India’s air “filthy”, referring to the high levels of air pollution, thus stirring up a hornet’s nest. There are people who believe Trump spoke but the truth, as the latest State of Global Air 2020, released by the US-based Health Effects Institute, has estimated that long-term exposure to outdoor and household air pollution contributed to over 1.67 million annual deaths from stroke, heart attack, diabetes, lung cancer, chronic lung diseases and neonatal diseases in India in 2019.

However, it is also being pointed out how Trump should be the last person to speak on pollution, as the US has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement, a global agreement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change with a goal to keep the world from becoming 2 degree Celsius hotter than before industrialization.

While the US has walked out of the Paris Agreement, India remains committed to this key agreement to limit global warming and the impacts of climate change. And various Indian states are taking several measures to address this burning issue.

As part of a recent event hosted by Climate Groups, a non-profit that works with business and government leaders to address climate change, in partnership with Climate Trends, a strategic communications initiative that focuses on climate change, representatives of state governments of Punjab, Delhi, Manipur, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh shared their climate initiatives and policy actions taken to address climate change.

It is clear that although COVID-19 remains an immediate danger, action on climate change cannot be delayed. But how good are the measures taken by the state governments to limit pollution and impacts of climate change?

Punjab’s ‘burning’ issue and air pollution

It is that time of the year when air quality in north India starts to dip with the onset of winter. In the national capital region of Delhi, the air quality has already hit the ‘very poor’ category. And the annual focus has shifted to the farmers of Punjab and Haryana who undertake stubble burning to prepare their fields for the next crop season of wheat, thus adding to the pollution.

Recognised as one of the significant activities degrading air quality, stubble burning in post harvest season results in the emission of a large number of pollutants. This burning is one of the major sources of aerosol and gaseous pollution.

In India, more than 500 million tonnes of crop residue is produced annually. Of this, 34 per cent comes from rice and 22 per cent from wheat crops, most of which is burnt in the fields. Twenty million tonnes of rice stubble is produced every year in Punjab, 80 per cent of which is burnt in fields.

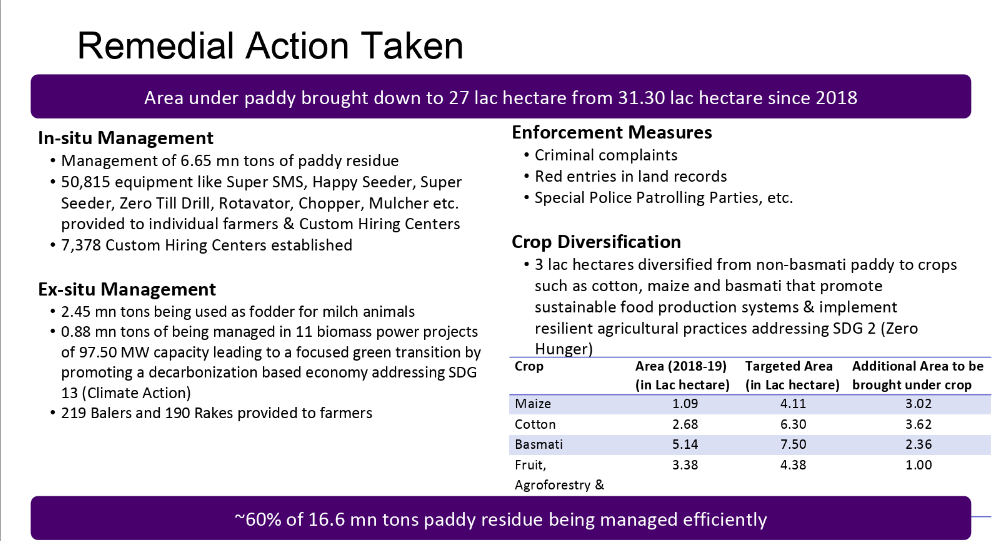

According to Alok Shekhar, principal secretary, department of Science and Technology, Punjab government, as a remedial action, the area under paddy in the state has been reduced from 31.3 lakh hectare since 2018 to 27 lakh hectare now.

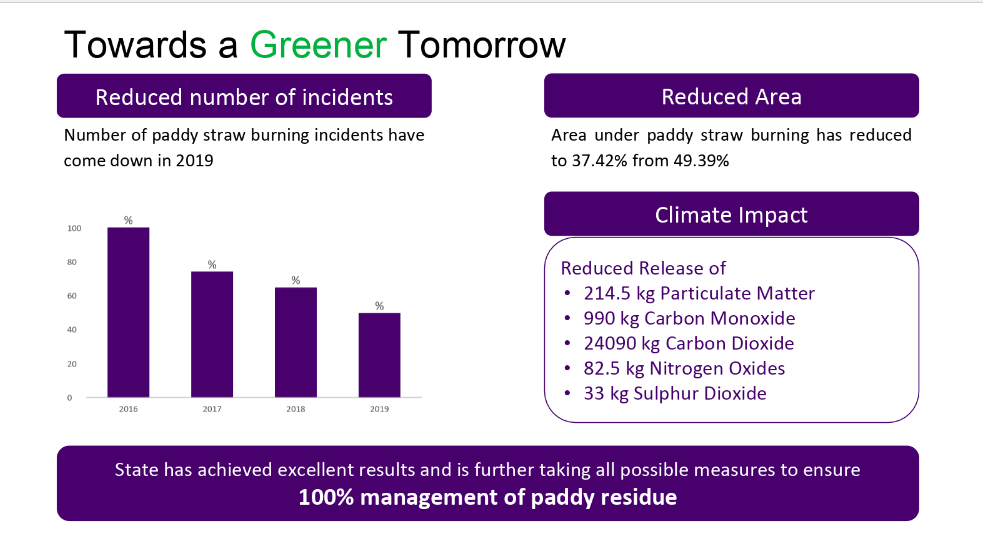

Similarly, area under paddy straw burning has reduced from 49.39 per cent to 37.42 per cent. Also, as per the state government, 60 per cent of the 16.6 million tonnes paddy residue is being managed efficiently in the state, he added.

For instance, 2.45 million tonnes is being used as fodder for milch animals; 0.88 million tonnes is being managed in 11 biomass power projects of 97.50 MW (mega watt) capacity leading to a focused green transition by promoting a decarbonization based economy, he explained. The state government claims that these measures have led to a reduced release of 214.5 kg particulate matter, 990 kg carbon monoxide, 24,090 kg carbon dioxide, 82.5 kg nitrogen oxides, and 33 kg sulphur dioxide.

During last month’s climate summit, Shekhar also shared that the Punjab government has also diversified around 300,000 hectare crops from paddy to cotton, maize and basmati to promote a sustainable food production system.

However, the challenges still remain.

In Punjab, stubble burning still continues and seems to be rising. Three days back, on October 21, there were 1,379 cases of field fires in Punjab, the highest for this season on a single day.

According to the Punjab Pollution Control Board, there were as many as 9,454 field fires in the last one month between September 21 and October 21 (There were 3,000 fires last year in the same time period). And the situation is likely to worsen. The burning cases were earlier increasing at the rate of 100-120 cases per day. Now it has crossed 1,000 mark daily.

Bijli Swaraj in Delhi

Clearly, the air pollution problem in Delhi cannot be blamed on the farmers of Punjab and Haryana alone. There is enough data to show how a large chunk of pollutants are from local sources of pollution, be it from vehicles, local power plants or construction activities.

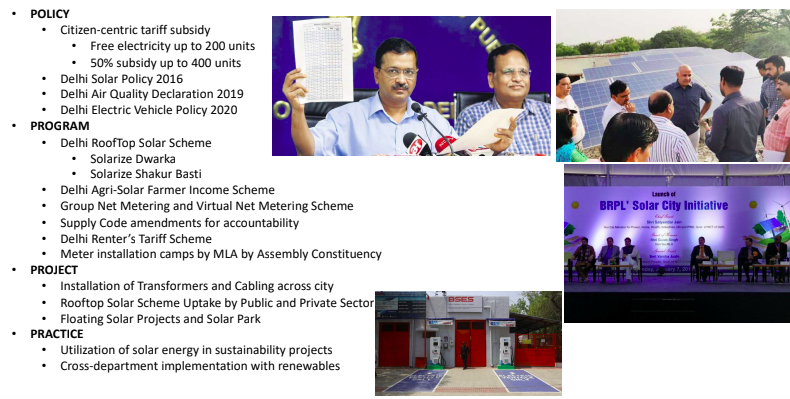

In order to reduce pollution from power plants and address climate change, Delhi government’s Bijli Swaraj, an electricity self-governance initiative, proposes shifting to renewable energy, creating green jobs and reducing dependency on fossil fuel, which could help reduce emissions.

“Earlier, Delhi received 80-85 per cent power from expensive power purchase agreements (PPAs). As of now, old PPAs and Discom performance is being negotiated. Besides, new PPAs of 1,940 MW of solar power and 750 MW of wind power have been signed,” said Roshan Shankar, advisor to the government of NCT of Delhi, during the event last month.

The state government has also shut down coal-based thermal power plants. Now, with rooftop solar scheme uptake by public and private sector, floating solar projects and solar park, the state government is utilising solar energy in sustainability projects. Reforms by the state government could reduce close to 1.6 million ton of CO2 emissions annually, he informed.

Towards carbon neutral gram panchayats…

About 2,500 kilometres south of the national capital, Meenangadi, a gram panchayat in Wayanad district of Kerala, is on the path to achieve carbon neutrality. It is recognised as the country’s first panchayat to work towards becoming carbon neutral.

“We all have been affected by climate change. Weather patterns in Wayanad are not as they used to be. As we confront global warming and climate issues, we have started a carbon neutral programme,” said Beena Vijayan, head of the local government, Meenagadi.

Watch the video

The panchayat has a population close to 35,000 and 66 per cent of its people are employed in the agricultural industry. The total CO2 emissions are estimated to be about 30,334 tonnes per year.

For the town to attain net carbon neutral status, volunteers and workers began to reforest the area to buffer temperature rise of 2 and 4.5 degrees celsius, which is predicted for the region by 2050. Rice fields are being converted to banana fields, and then to areca nut, coffee, and cardamom — crops that are thermo-sensitive and vulnerable to climate change.

Children in the local schools have planted bamboo trees, which act as a valuable sink to carbon storage. In this region bamboo has the potential to offset upto 4,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per hectare.

Apart from plantations, waste management is also being ensured. Workers from Harita Karma Sena of Green Army ensure that waste is segregated at source. They go door-to-door to collect plastic waste and other recyclable waste. They bring it to a resource recovery centre set up under the carbon neutral programme.

“People now carry their own bags when they go out for grocery shopping. They have stopped using plastic at stores. Plastic consumption in households has dramatically decreased,” said Suni who manages the facility with 32 staff workers.

With the existing plans, about 15,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions can be reduced each year. “If all these programmes are implemented properly then we might be able to achieve this ambitious project. We hope that the number of new trees we have planted will help to sequester the excess carbon,” informed Vijayan.

… and carbon neutral villages

Over 3,800 kilometres away from Meenangadi gram panchayat, Phayeng, a small village in Imphal West district of Manipur in northeast India, has been given the tag of being a carbon positive village. A village is given the carbon positive tag if it sequesters more carbon than it emits.

Phayeng is surrounded by three densely forested hillocks with fruit trees in the centre and a stream flowing through it. The village, which is vulnerable to climate change, faces forest degradation and water scarcity. Women in the households are exposed to black carbon as they use traditional cooking methods. The river that flows along the village is the only source of water for villagers. The river is becoming seasonal due to drying of the upstream. This also restricts farmers to cultivate just a single crop a year due to non-availability of water. Heavy rains often cause flash floods and there is a decrease of run-offs and soil moisture recharge. A large number of villages who are dependent on agriculture activities were switching to other jobs.

However, the village has been resurrected from its vulnerability through community participation and funding under the National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change (NAFCC), a central scheme to support adaptation to climate change impact in various states.

“Over one lakh fruit bearing and medicinal plants were planted at the 218 hectares degraded forest land through community participation,” informed M H Khan, additional chief secretary, Department of Forest and Environment, Manipur.

“One of the targets of the state government is development of water harvesting ponds for 218,640 cubic metres capacity. Construction of pick up dams within the rivers, and enhancing the canals for 20 km is under progress through community participation,” he explained.

Phayeng, with less than 3,000 inhabitants, is the first in the state that has completely transformed itself from being a barren, deforested land to a thriving ecosystem.

There are more plans to further reduce its carbon emissions. The village is set to receive a grant of Rs 10 crore under the National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change to facilitate afforestation in the catchment of the river Maklang that flows along the village. The fund will be utilised for creation of water bodies, introduction of climate change-resilient varieties of crops, installing of solar lights, setting up a community piggery and poultry farm and an eco-resort, besides replacing firewood in the kitchen with cooking stoves.

Reviving water bodies to tackle climate change

Indore in Madhya Pradesh, vulnerable with regard to availability of water, is focusing on rejuvenation of 330 traditional water bodies in the city to develop resilience with respect to climate change, which poses unique threats to its water supply system.

The state is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to its topography and social structure with around 70 per cent of its population living in rural areas.

Indore’s major supply of freshwater comes from the Narmada river, 70km away. This results in an unreasonable cost of pumping water. Since traditional water bodies are in a derelict state, it increases pressure on groundwater extraction.

Bhopal-based Environmental Planning and Coordination Organisation (EPCO) has developed a plan to identify and rejuvenate water bodies. The project started in March 2017 and is funded by the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change under the Climate Change Action Programme .

“This project aims at enhancing adaptive capacity to climate change through conservation of traditional water supply sources – wells and baoris of the city in collaboration with the city’s municipal corporation,” explained Tanvi Sundriyal, executive director, EPCO, Department of Environment, Madhya Pradesh. The project will further reduce the burden of the existing water distribution system using de-silting and dewatering technology.

The project will also investigate the traditional water sources in the city, prepare ward-wise GPS location of water bodies and a GIS mapping of locations; it will study the current status of water bodies and supply systems. It will also estimate the cost of renovation and revival of water bodies; suggest and recommend the restoration and revival of traditional water bodies.

India’s commitment under the Paris Agreement

On October 2, 2016, India ratified the Paris Agreement. Its climate pledge included three targets. First, to reduce the emission intensity — a ratio of total emissions to gross domestic product — by 30-35 per cent from the 2005 level by 2030.

Second, to ensure that 40 per cent of its electricity-generation capacity comes from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. Third, to create a cumulative carbon sink of 2.5-3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030 through additional forest and tree cover by 2030.

Some countries— China, The EU28, India, Mexico, Russia, and Turkey — are projected to meet their unconditional Nationally Determined Commitment (NDC) target emission levels under the Paris Agreement. India is one among three countries estimated to meet or exceed its NDCs emissions target. But there are others who warn that the government needs to correct course where its policy is faltering.