Cold wave, rainfall anomaly, floods, drought, heatwave and cyclones — 2019 sets new records in extreme weather events

The year 2019 will be remembered for breaking several previous records of extreme weather events be it the cold wave, large-scale rainfall anomalies, or the number of cyclones

North India is in the grip of a severe cold wave. As mercury plummets, several cities have reported temperatures way below their normal winter temperature.

On December 30, the national capital of Delhi broke its 119 years old record of most coldest day in the month of December. The city recorded the lowest ever day maximum temperature of 9.4 degree Celsius (C) at Safdarjung. The minimum temperature recorded at the same station was 2.6 degree C. According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), “it is the lowest ever day maximum temperature for the month of December based on the data of 1901 onwards.”

In the neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh, an intense cold wave has allegedly killed 28 people. Scientists are blaming “robust spell” of Western Disturbances — an extra-tropical storm that originates in the Mediterranean region and brings winter precipitation to North India — for the prevailing cold wave conditions in North India. The IMD has forecasted severe cold wave to abate after January 1, 2020.

“The cold wave is directly related to the Western Disturbance, which causes cold air from aloft to come to lower altitudes, thereby causing cold weather… Over the past two-three years, the Western Disturbances have increased in frequency and duration, as they last from December to March as opposed to January and February few years back,” said Sridhar Balasubramanian, associate professor of mechanical engineering and an adjunct faculty member at IDP Climate Studies, IIT Bombay.

According to him, the intense cold wave could be broadly related to the Arctic polar dynamics, where most of the winter storms originate and make way to lower latitudes. “The polar vortex, which is a low pressure that keeps cold air near Arctic, has been weaker this year, thus allowing cold air to move Southward. This could be the reason for the cold wave in North India,” he added.

But, very low winter temperature is not the only way in which the year 2019 has broken previous records of weather events in the country. The entire 12 months of the year have witnessed one extreme weather event after another then be it heavy rainfall during the monsoon season or the number of cyclones in the Arabian Sea.

“Definitely, 2019 was an exceptionally different year in terms of large-scale anomalies in heavy rainfall events, heat wave and flash floods in several cities like Mumbai and Pune,” M Rajeevan, secretary, Union ministry of earth sciences told Gaon Connection.

“Frequency of extreme weather events is increasing ever year and this year [2019] we have experienced more such events. It is part of the global warming scenario and such events are likely to increase,” he added (see interview: “2019 an exceptional year of large-scale weather anomalies”).

A dry start

The year 2019 started with almost half the geographical area in the country facing acute water stress and drought conditions. This was primarily due to several regions in the country receiving ‘below normal’ rainfall in 2018’s both southwest monsoon (June to September) and northeast monsoon (October to December).

For instance, during 2018’s southwest monsoon season, Maharashtra received deficient rainfall of minus 22 per cent triggering kharif crop failure and drought in several pockets of the state.

Not only Maharashtra, even states like Gujarat, Bihar, Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh, etc declared drought. And, by March-April 2019, water crisis in the country had turned acute, as there was loss of both kharif and rabi crops and acute fodder shortage. Further, pre-monsoon season of 2019, March to May, registered a cumulative rainfall departure of minus 24 per cent, thereby worsening the water crisis.

The situation in Chennai city turned critical and it had to be supplied water a through ‘water train’. Between July and October 2019, the ‘water-train’ made 159 trips and transported about 420 million litres of water to the southern city for which the Chennai Metro Water paid Rs 8.60 lakh per trip to the Southern Railways.

Heatwave followed

While half the country was dealing with drought, heat waves hit several parts of the country as early as March 2019. Within a month, by the first week of June, the country underwent 73 spells of heatwave, 11 of them severe, reported Down To Earth.

Bihar, already facing acute drought, was one of the worst affected states, as 184 people died in a heatwave in the state. Situation was so critical that Section 144 had to be imposed in Gaya district.

An analysis by India Spend showed more than 65 per cent of the country’s population was exposed to heatwaves in May and June 2019. Also, July 2019 was the hottest July ever in recorded history of the IMD. The only relief in sight was the southwest monsoon, which too was ‘unusual’.

Delayed onset, but ‘above normal’ monsoon

Against the normal onset date of June 1, the southwest monsoon arrived over Kerala on June 8, 2019. Thereafter, the progress of monsoon was slow. It hit Mumbai only on June 25, the most delayed it has been in the last 45 years.

By June 26, 2019, of the total 36 meteorological subdivisions in the country, 31 were in ‘deficient’ and ‘large deficient’ rainfall category. And, there was a deficit of minus 36 per cent rainfall in the southwest monsoon season. There were serious fears of drought aggravating in the country and 2019 ending as a drought year.

However, the tables turned soon. Bursts of heavy monsoon rainfall, brought the rainfall deficit down from minus 33 per cent in June end to minus 9 per cent within a month. However, till July 2019 end, almost 45 per cent area of the country was still facing drought conditions. This was primarily due to erratic rainfall, as some parts of the country received extremely heavy downpour, whereas others remained dry.

For instance, till July 31, 2019, with half the monsoon season over, Beed, Parbhani, Latur, and Nanded districts in Maharashtra had a rainfall departure of minus 37 per cent, minus 35 per cent, minus 35 per cent, and minus 23 per cent, respectively. But, overall Maharashtra state was in ‘normal’ monsoon category.

Further, very heavy rainfall lead to floods in several parts of Maharashtra. Not only Mumbai and Pune cities, even districts like Kolhapur and Sangli faced one of the worst floods in their recent history.

Rainfall records in 2019

The city of Mumbai broke its previous record of annual monsoon rainfall, as between June and September 2019 it received about 3,700 millimetre (mm) rainfall at the Santacruz observatory, the highest ever rainfall. Its annual average monsoon rainfall is about 2,300 mm.

The IMD had forecasted a ‘normal’ southwest monsoon of 2019. However, the country received ‘above normal’ (110 per cent of long-period average or LPA) monsoon rainfall.

“When we issued our seasonal monsoon forecast in May 2019, El Niño was blooming at that time. But, Indian Ocean Dipole was developing, so we forecasted a normal monsoon,” said Rajeevan. “But, the Indian Ocean Dipole became a very big event, which rarely happens. Because of this large-scale Indian Ocean Dipole, we had excessive rainfall, especially in the month of September 2019,” he added.

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon in the Indian Ocean. It is normally characterized by anomalous cooling of sea surface temperature in the southeastern equatorial Indian Ocean and anomalous warming of sea surface temperature in the western equatorial Indian Ocean (Arabian Sea).

In its press release dated September 30, 2019, the IMD noted “in spite of late monsoon onset and large deficient rainfall during the month of June, the seasonal rainfall ended in above-normal category with 110 % of LPA. Monsoon rainfall during July, August and September were 105%, 115% and 152% of its long period average, respectively.”

Interestingly, the last time the country as a whole received 110 per cent of LPA rainfall in southwest monsoon season was in 1994. Also, after 1931, this was the first time the seasonal rainfall in 2019 was more than LPA even after the June rainfall deficiency was more than 30 per cent of LPA. The September 2019 month rainfall was the second-highest since 1917, when it had rained 165 per cent of LPA in September 1917.

Massive floods

Predictably, heavy rainfall brought massive floods to several parts of the country, which were earlier struggling with drought. For instance, in mid-July 2019, heavy rainfall lead to floods in north Bihar, as river embankments breached and about 130 people died. Floods in the state affected over 2.5 million people in 12 districts.

Around the same, an excess weekly rainfall of up to 250 per cent above normal brought massive floods in northeast India. Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Tripura and Manipur were inundated. Over 4.5 million people in Assam were affected by the rising waters and the state recorded 28 deaths due to floods.

Maharastra, which was facing successive drought, too, had floods due to bouts of heavy rainfall. Between July 25 and July 31, Kolhapur received 105 per cent more rainfall than its weekly normal. Nashik district received 358 per cent above normal rainfall during the same time period. Satara and Sangli districts had 161 per cent and 159 per cent above normal rainfall in the last week of July, respectively. This brought unprecedented floods in the region causing large-scale damage to the Kharif crops.

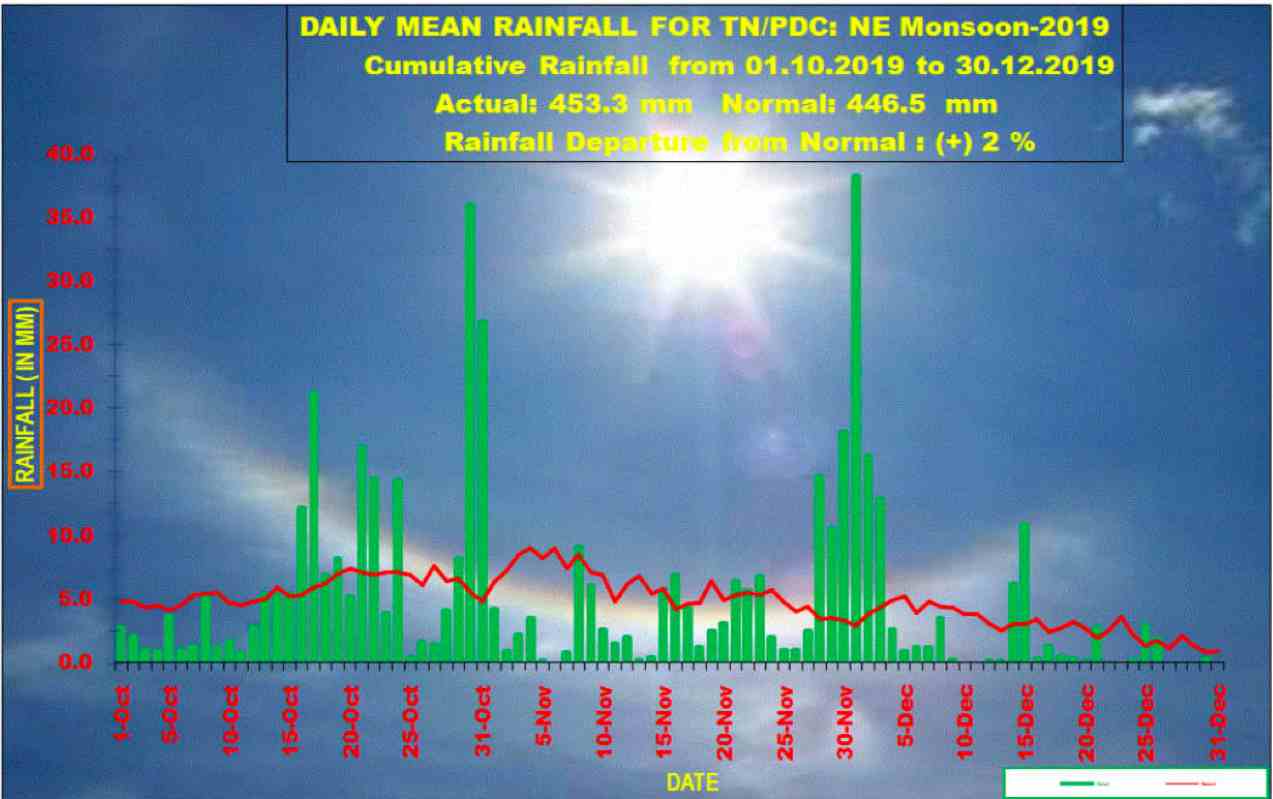

Meanwhile, the northeast monsoon 2019 also brought floods in southern India. In early December 2019, heavy rainfall-induced due to a strong ‘tropical wave’ pulled Tamil Nadu out of ‘deficient’ rainfall category, but not without bringing floods. At least 25 people died in Tamil Nadu due to heavy rainfall related incidents. Data collected by IMD’s Regional Meteorological Centre at Chennai shows the ‘peaks’ of rainfall during the northeast monsoon of 2019 (see graph: Daily mean rainfall for Tamil Nadu and Puducherry in NE Monsoon 2019).

Graph: Daily mean rainfall for Tamil Nadu and Puducherry in NE Monsoon 2019

Record cyclones in the Arabian Sea

The year 2019 will go down in the history of weather events as the year with the highest number of cyclones — seven cyclonic storms — in the Arabian Sea (based on data between 1891 and 2018). The last time such a high number of cyclones were formed in the Arabian Sea was in 1998 with six such storms.

As per the IMD, 11 cyclonic disturbances developed over the north Indian Ocean including four over the Bay of Bengal and seven over Arabian Sea in 2019. “Thus, the Arabian Sea has been more active during 2019 with the formation of 7 CDs against the normal of 1.7 CDs per year. Similarly, 4 cyclones have developed over Arabian Sea against the normal of 1 per year,” the weather agency noted.

This is not all. The year 2019 also witnessed the development of more intense cyclones over the Arabian Sea. Cyclone Vayu (June 2019) and Hikka (September 2019) were very severe cyclonic storms; Cyclone Maha (November 2019) was extremely severe cyclone storm; and super cyclonic storm Kyarr (October 2019).

According to Rajeevan, one of the reasons for record number of cyclones in the Arabian Sea could be warming of the ocean. “The Arabian Sea is warming much faster than the Bay of Bengal,” he said. Normally, the Arabian Sea is sluggish in terms of tropical cyclone formation. “But, last few years we have found that not only the sea surface but even till the depth of 150 metres, the ocean is warming up very sharply. And, it is this ocean heat content, which is contributing to tropical cyclones,” he explained.

Clearly, the writing is on the wall. We need to prepare for more extreme weather events and disasters. And, building climate resilience is the only way to move forward.