Despite suffering major losses, vegetable farmers in Jharkhand continue to be hopeful

Whenever I came across news of farmers committing suicides, I could never understand the gravity of the problem. But, since the lockdown, I have finally understood the reason

Whenever I came across news of farmers from Maharashtra or Punjab committing suicides, I would feel nothing. I could not understand the gravity of the problem or the situation under which farmers committed suicide. It felt strange. But, since the corona lockdown, I have finally understood why farmers are compelled to commit suicide.

“The price of cabbage, which normally sold at Rs 20 per kg, has come down to Re 1 during the lockdown. It’s labour cost is more than that.”

“We didn’t expect and we didn’t get any help from the government. However, we do not want anything else from the government, but for the supply chain to be restored.”

“Lockdown did what it had to. The weather had already been disastrous – there were five-six hailstorms during the lockdown. The entire crop was damaged. Hopefully, now everything will be fine.”

There are some of the most common problems that one will come across while interacting with vegetable farmers from Ranchi in Jharkhand, which is considered to be the vegetable bowl of the country. Ranchi and its surrounding areas supply vegetables to other parts of Jharkhand and Bengal and Odisha. Most of them are small farmers and there is no effective cooperative association of these farmers. There is a big vacuum in the name of infrastructure. In most of the places, basic facilities, like cold storages, are also not available to vegetable farmers. Bigger farmers with sound networking may have suffered less during the lockdown, but the produce of small farmers has been sold for almost nothing.

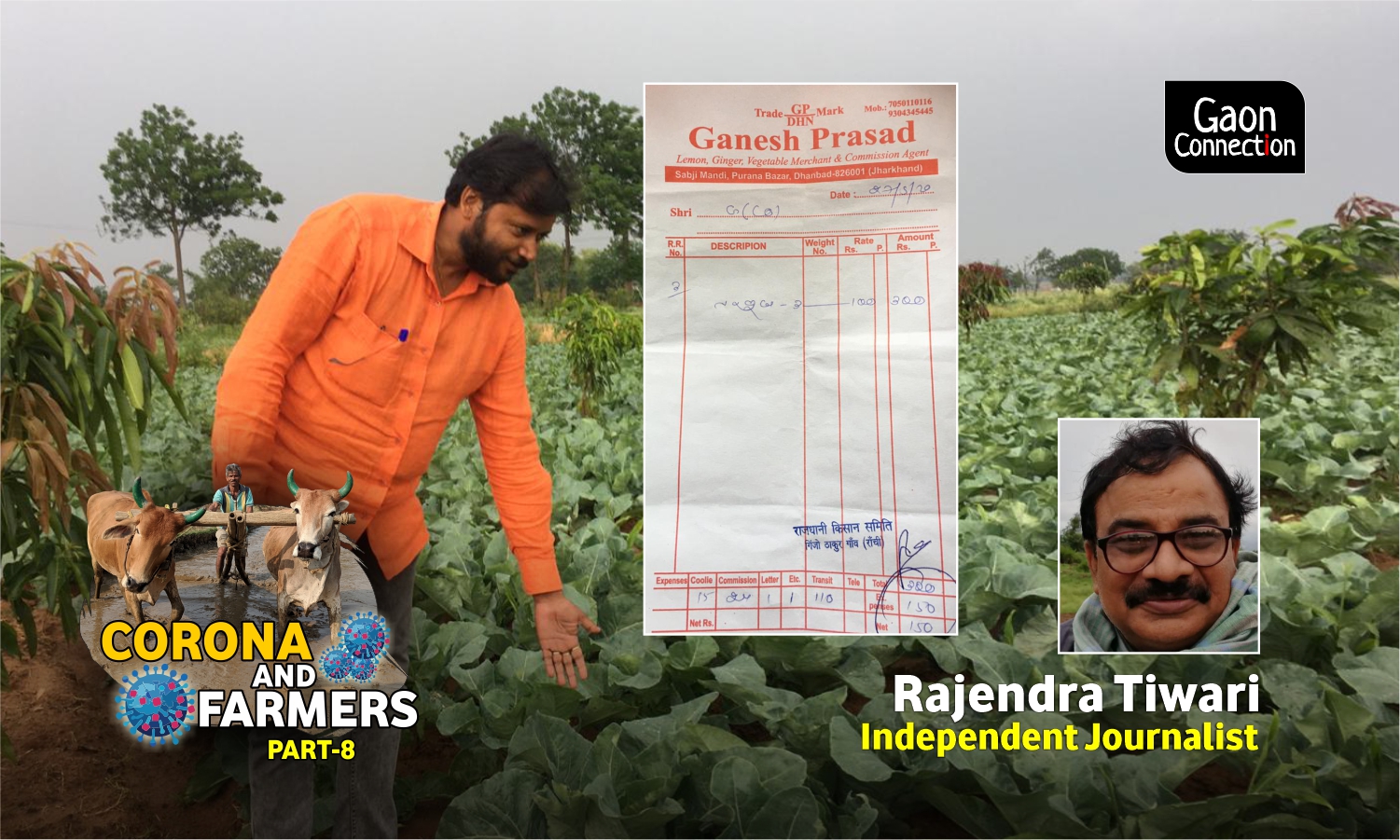

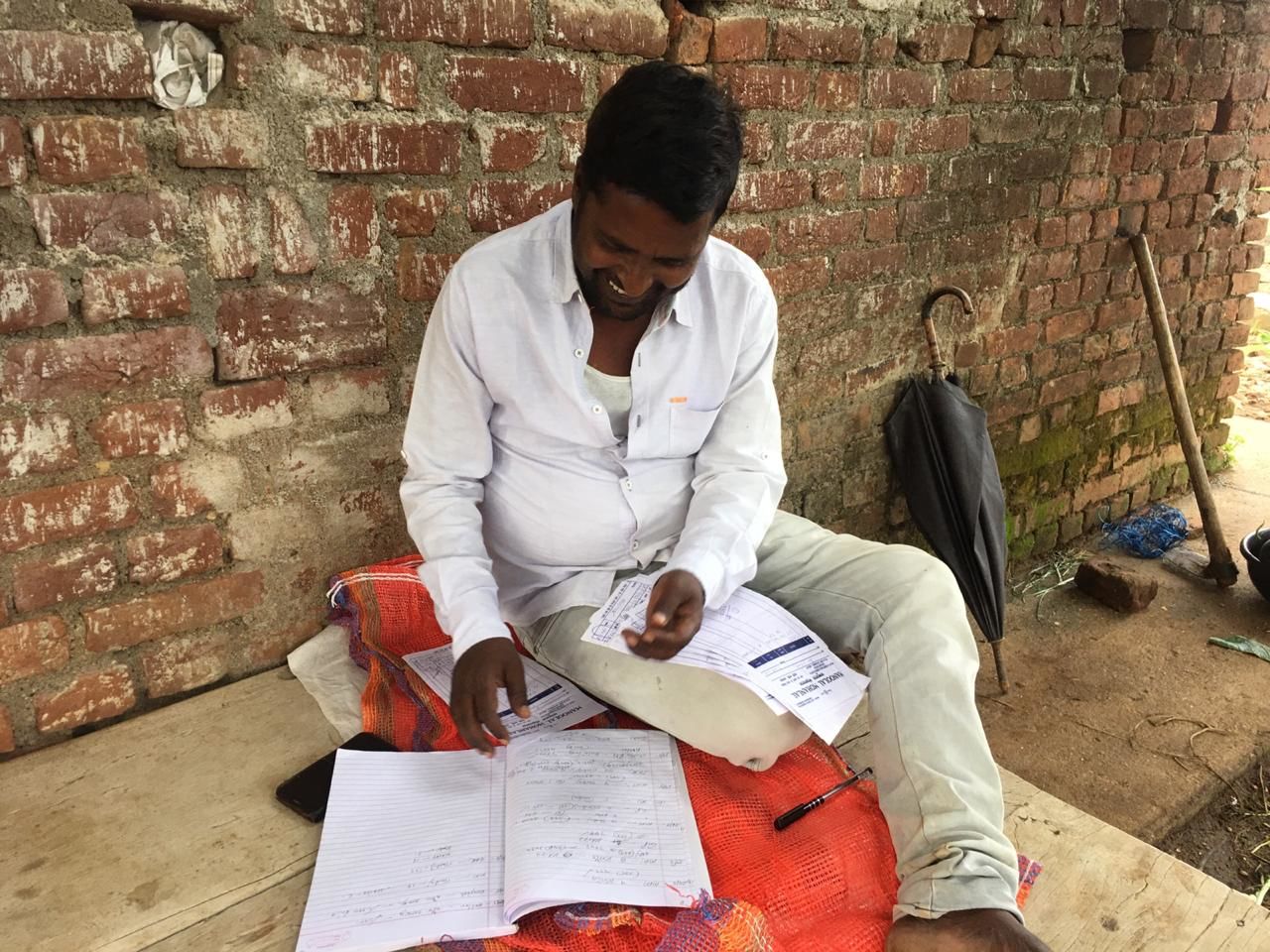

Abdul Kudus, a vegetable farmer from Choraiya village of Mander block in Ranchi, puts forward receipts as an evidence and says: “Just see, watermelons were sold for Re 1 a kg. I sold 300 kgs watermelon went for Rs 300. The cost of watermelons at the mandis was Rs 150, and I got Rs 150. I had cultivated watermelons in my two acres farm in hope of a good margin, but Allah’s wish was something else.” Yet, he is hopeful. “Now that the lockdown is going to end, things would improve. By tonight, one of my trucks of watermelons is reaching Sealdah. Perhaps, this time I shall get a good rate,” he said.

Ashutosh, who cultivated flowers with vegetables, looked very worried. The entire season of weddings went away in the lockdown. He will not get anything for the flowers that he has cultivated, but he will still have to pay labourers so that these flowers can be picked. However, his face brightens up when he shows his cabbage field. He is hoping things would fall in place once the lockdown ends. He does not rule out the possibility of further losses due to poor crop of cabbage, but then he says: “Such is the life of the farmers. Every crop symbolises new hope for us.”

A farmer-friend who has recently landed in vegetable cultivation, says: “Besides the lockdown, I was also hit by the erratic weather conditions. Storms, rain as well as hailstorms did a lot of damage. My entire field was destroyed in a hailstorm last week. What had I thought and what is actually happening? I had thought that perhaps after a week, the lockdown would be over, the demand would increase and some of our losses would be compensated for. But our expectations were short-lived.”

Abdul Kudus shows the vine of karela (Bitter Gourd) that had fallen due to rains and hail. The labourers were putting them in order. He says: “I am selling Karela for Rs 5 a kg while it used to fetch at least Rs 30-35. One seed of karela costs us Rs 4. On top of all this, it is costing me extra money to straighten the karela vine due to the weather. We have no other alternative.”

The biggest problem of vegetable farmers is that they cannot even stop the cultivation. If one vegetable crop gets spoiled, they have to spend more to hire labourers in order to throw it away. It means that the farmer would get nothing and would lose more money instead. Ropna Oraon from Bagicha Toli says: “Now, take for example cabbage. We are selling it for Re 1. You calculate whether we’d be able to earn anything at all? The lockdown is also causing a lot of loss in the local market. There is a usual loss of 5 kgs upon fifty-sixty kgs. If you speak up, you call for your own harm.” All the hopes of Ropana Oraon are now pinned on the potato and ginger crop.

Abdul Kudus and Ashutosh also talk about these losses. All Ashutosh wants is the government should restore the supply chain to other cities and states. It will solve a lot of problems.

Mukhtar Ansari from Kadam Toli village sums up the reality. “Cauliflower were sold for Re 1 … let it be. All will be well ahead. We are farmers. We live on hope. This crop got ruined, no worries. All will be fine in the next crop. This is exactly how we live. Whom do we complain?” he asked.