Mahoba/ Unnao/ Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

With their mother living over 600 kilometres away in New Delhi, where she works as a construction labourer, teenage sisters Muskan and Nitisha consider their smartphone a constant companion and guide.

Fifteen-year-old Nitisha, a resident of Mirthila village in Mahoba, Uttar Pradesh, dreams of opening a tailoring business after her intermediate (class 12). Her internet-enabled phone helps her keep pace with trending kurta and blouse styles.

Meanwhile, her elder sister, 16-year-old Muskan, follows a daily exercise regimen with the help of YouTube videos she watches on the smartphone, which is shared by both the sisters. In the absence of any formal tailoring centres or gyms in their village, the internet is the sisters’ best bet to arm them with information to try and make it big in their lives.

Not very far away from the house of these sisters in Mirthala village, lives their aunt, Meera Devi. As soon as she gets time off the household chores, the 24-year-old sits down with her smartphone and searches for information on ways to prevent miscarriages.

“I have been trying to get pregnant ever since I got married four years ago but have suffered repeated miscarriages,” Meera told Gaon Connection. “I have heard there are good doctors in bigger cities, so I keep looking up for them on my phone,” she added.

The advent of internet access on smartphones and their deep penetration in the villages of the country have transformed the lives of rural women, unlocking a myriad of opportunities that were once beyond their reach.

With smartphones and internet data plans becoming increasingly affordable and accessible even in remote areas, these women, many of them young teenagers, can now tap into a wealth of knowledge and information at their fingertips.

Kalpana dreams of entering police services. The 22-year-old is hooked on to the online coaching portal of Physics Walla to prepare for a competitive examination to enter police services.

Babli spends a large part of her time scrolling down her Instagram feed to find new recipes.

For instance, Kalpana dreams of entering police services. But there are no established tutoring centres in her hometown Mahoba, so the 22-year-old is hooked on to the online coaching portal of Physics Walla to prepare for a competitive examination to enter police services.

Her younger sister, Babli, has no interest in physics but spends a large part of her time scrolling down her Instagram feed to find new recipes. The day Gaon Connection met the young woman, she was trying out a fried rice recipe she had seen on Instagram, on her firewood chulha.

The internet on smartphones has become a powerful catalyst for rural women’s economic and social empowerment. Nielsen’s India Internet Report 2023 reveals that India has more than 700 million active Internet users aged two years and above as of December 2022 — 425 million (61 per cent) of whom are registered in rural India.

Nearly half of the rural population is online with a usage surge of 40 per cent in 2022 as compared to 2021, the report noted. Interestingly, female users grew by 27 per cent as compared to its male counterpart that grew by 18 per cent between 2021 and 2022.

The internet on smartphones has become a powerful catalyst for rural women’s economic and social empowerment.

Explaining the survey that led to the report, Ashish Agarwal, Marketing and Communications Leader with Nielsen Group said that with a total of 35,000 households which translates to around 1,50,000 individuals were surveyed face-to-face in systematic random surveys across all states.

Video calling was recorded as the top preferred activity for female internet users in rural India. Other activities include video watching (59 per cent), social networking (51 per cent), online music (44 per cent), and chatting (45 per cent).

Also Read: Bharat is surfing more internet than India

Closeness and comfort

Video calling her daughters, aged 10 years and seven years, provides comfort to Mangli Bai who has left behind her young children on account of their school in her village in Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, and migrated along with her husband to Hafizabad village in Unnao, Uttar Pradesh to work in a brick kiln.

“The phone keeps me closer to my village. Everytime I leave my children behind I worry about them. I video call my daughters and feel better,” Mangli Bai told Gaon Connection. She also watches Chhattisgarhi songs and movies on her small mobile phone to remain connected with her roots.

The mobile phone, the conversations with her daughters, and the movies and songs she watches are the link with her home state. “My wife enjoys watching songs and serials on YouTube. I leave to work on the bhatta at six in the morning, and after a small lunch break around noon, continue working till six in the evening. She also accompanies me but takes more breaks to manage household chores,” 35-year-old Leela Ram told Gaon Connection. It was he who three months back bought a smartphone, which is mostly used by his wife.

Mangli Bai has migrated from Chhattisgarh to work on a brick kiln in Uttar Pradesh. The mobile phone, the conversations with her daughters, and the movies and songs watches are the link with her home state.

The couple makes about Rs 11, 000 a month at the brick kiln, some of which is sent back home. Their earning is barely keeping them afloat, but Leela Ram thought it important enough to invest Rs 11,500 on a smartphone, which he bought on instalments and has to pay Rs 500 a month for 11 months.

“Everyone has it, I wanted it too,” said Leela Ram.

In a corner of the brick kiln where Leela Ram and his wife Mangli Bai work, there are seven other families living in the make-shift huts, and each one owns at least one smartphone. Most of the time it is the women in the family who use them the most.

Usha Patel, Mangli Bai’s neighbour, bought her phone just two months ago but is already considered something of an expert in operating it.

“Whenever we go to other states for work, we are bored. Unlike the men, we can’t roam around talking to strangers. This phone has helped us cope with the boredom,” 34-year-old Patel told Gaon Connection.

Kiran Kumari, mother of teenage sisters Nitisha and Muskan from Mirthila village in Mahoba, agreed. “It is Bhojpuri movies on my mobile phone that help me unwind in Delhi after a back-breaking day at work,” she said. She was visiting her village in Uttar Pradesh when Gaon Connection caught up with her and her daughters.

Bridging the gap

Ten years ago, Dayawati was one of the first residents of her village in Hafizabad, Unnao, to own a smartphone. The gadget was gifted by her husband who worked in the Gulf. Today, almost all the households in her village have a smartphone, and a mobile phone shop opened in her village five years ago, which is doing brisk business.

“It is this phone which has kept me going. Both my husband and my son work in the Gulf. They are so far away from home. Seeing them gives us tasalli (relief),” 42-year-old Dayawati told Gaon Connection.

Video calling was recorded as the top preferred activity for female internet users in rural India.

Lads in her village help Dayawati recharge her internet pack once every three months, which costs her Rs 750.

For 21-year-old Reeta Sharma, her smartphone has a strong emotional value. It is a wedding gift by her husband and the phone is now her constant companion in her village in Hafizabad where power cuts are frequent.

“I got it recharged when I went to my mayke for a three month-data pack. I feel shy to ask in my sasural,” newly-married Reeta Sharma, told Gaon Connection. Instagram reels are an answer to her boredom, she added.

For many women like Rajni Tripathi who lives in a joint family in Sitapur, Uttar Pradesh, her husband’s mobile phone is a saviour.

“Usually my father-in-law or my children watch something on the TV, and I cannot ask them to switch channels. So I slip away somewhere quiet and watch my favourite soaps in peace on YouTube or FaceBook,” she smiled.

For many women like Rajni Tripathi who lives in a joint family in Sitapur, Uttar Pradesh, her husband’s mobile phone is a saviour.

The Nielsen Internet report points out that 85 million smartphone users in rural India share their devices, primarily to watch videos. It also observed that cheap data and smartphone availability has democratised video watching.

“The access to the internet is still very unequal, but young adults in rural areas, including women, are very curious about the world beyond their villages. Their aspirations for their lives and selves are changing,” Natasha Susan Koshy, Senior Research Associate, IT for Change, a non-governmental organisation based in Bengaluru, told Gaon Connection.

According to her, the numbers in the recent Nielsen Internet report can’t be considered absolute.

“We are seeing some change because of the rates at which one can access digital infrastructures, but numbers in themselves are not indicative of social change. Family arrangements, patriarchy, access to finance, ownership practices and status within households all shape women’s engagement with the digital world,” said Koshy.

At the same time, Koshy pointed out that aggregated findings may not represent local specificities, and there may be large variations across states, districts, blocks and villages.

“Women do not out migrate — especially outside their home states — as much as men, and may be less familiar with languages not specific to their locations. To make digital content more accessible to them, it is important that it be developed in regional languages. In the absence of such efforts, the gender digital divide will only widen,” she pointed out.

Though the gap between the male and female internet users have reduced over an year, the female population still lags, as only 47 per cent of them are active internet users as compared to 53 per cent males, as noted in the Nielson’s survey report.

ASHAs and self-help groups

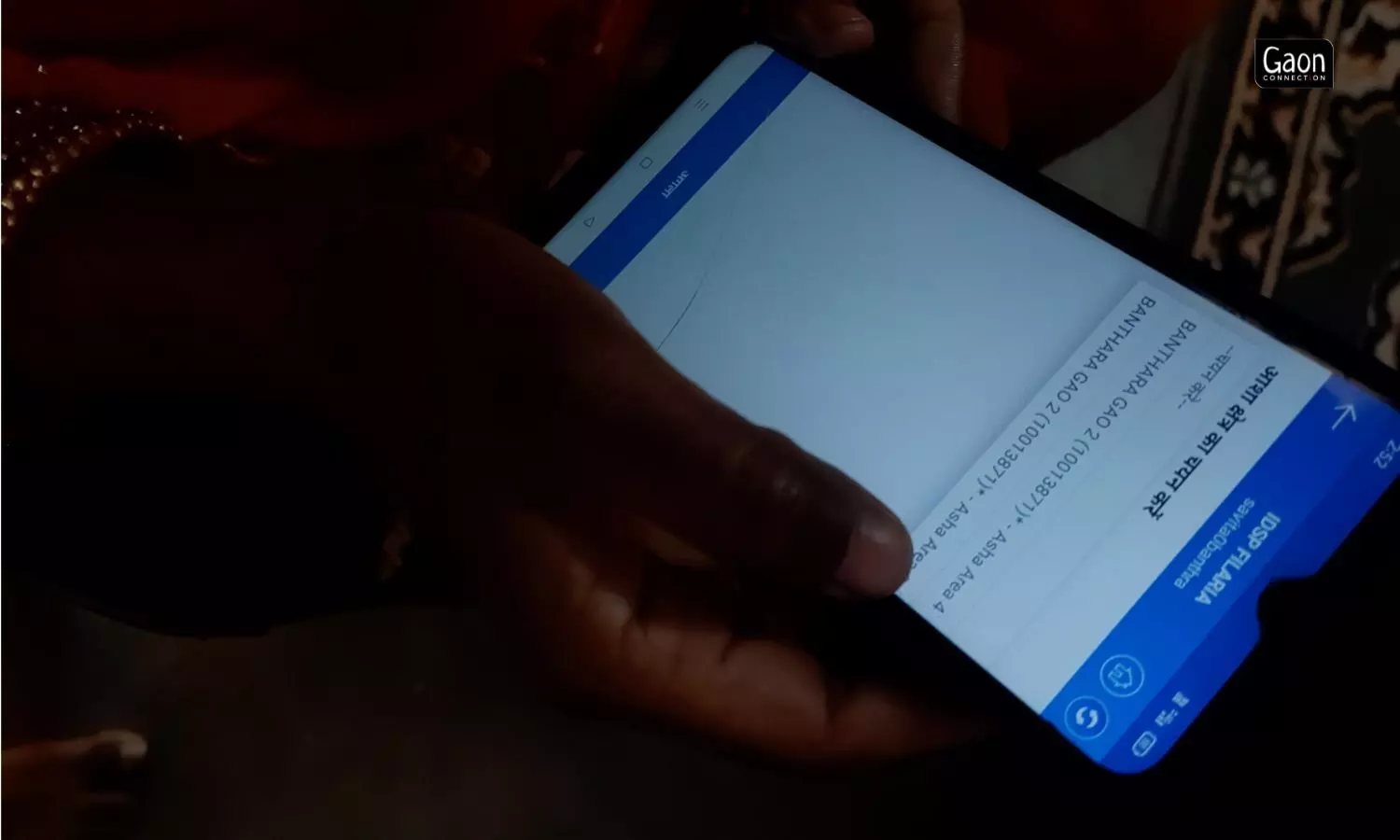

Sandhya has been an ASHA [Accredited Social Health Activist] in Banthra village of Sarojini Nagar block in Lucknow since 2019. As part of her work as a frontline health worker, 34-year-old Sandhya has to maintain records of family surveys, etc., through the digital application e-kavach.

“Now all the work we do has to happen using smartphones and the internet,” Sandhya told Gaon Connection.

Like Sandhya, hundreds of thousand ASHA workers across the country use internet-enabled smartphones to carry out their daily duties. There are 160,132 rural women serving as the ASHAs.

Like Sandhya, hundreds of thousand ASHA workers across the country use internet-enabled smartphones to carry out their daily duties.

This is not all. Even women self-help groups are now connected with the internet through smartphones. Women use smartphones for ecommerce purposes and connect with buyers and traders to sell a variety of products they manufacture. E-commerce businesses have multiplied manifold since the pandemic.

For instance, according to data from Uttar Pradesh State Rural Livelihoods Mission, Department of Rural Development, out of 7.4 crore rural women across the state, 11 per cent or 0.82 crore are part of self-help groups in Uttar Pradesh. These SHG women regularly use digital applications on phones to facilitate the functioning of their groups.

This article is written under the Laadli Media Fellowship, 2023. All the opinions and views expressed are those of the author. Laadli and UNFPA do not necessarily endorse the views.