Extreme weather events linked to climate change increase vulnerabilities of migrant workers in Indian cities: Study

Lack of jobs back home and a rise in extreme weather events, such as the recent heavy rainfall in Mumbai, is leaving migrant workers vulnerable in metropolises. Researchers of a new study warn that migration is expected to increase in the coming decades thereby increasing climate hazards in megacities.

With heavy rains also occurring across megacities, the tension is ripe about urban areas. Photo: Pushkar V/Flickr

A large-scale migration towards megacities, such as Mumbai and Delhi, already facing increasing climate threats due to extreme weather events, is leaving the migrant workers at risk.

For instance, the most adverse effects of heatwaves in Delhi affects its migrant workers community as it resides in closely packed dwellings, often made of tin-sheds with poor ventilation.

Similarly, increased coastal flooding in Mumbai, which is being experienced these days in the southwest monsoon season as the metropolis has been receiving very heavy rainfall in the past couple of days, affects its migrant labourers who live in low-lying ill-planned ghettos. In the past few days, heavy rainfall related accidents have reportedly killed 31 people in the financial capital of India.

These increased risks of fast changing climate on India’s migrant population have been documented in a recently released study titled ‘Climate hazards are threatening vulnerable migrants in Indian megacities’. It was published yesterday, on July 19, in Nature Climate Change, a reputed international journal.

The study pointed out that climate-related hazards paint an alarming scenario in which the major migrant destinations will emerge as hotspots of climate-induced disruptions, wherein vulnerable migrant workers are expected to be the most affected.

“The lack of basic resources — such as proper shelter, healthcare and clean drinking water — for these segments of population may therefore make them more susceptible to higher health risks,” warned the researchers in the study.

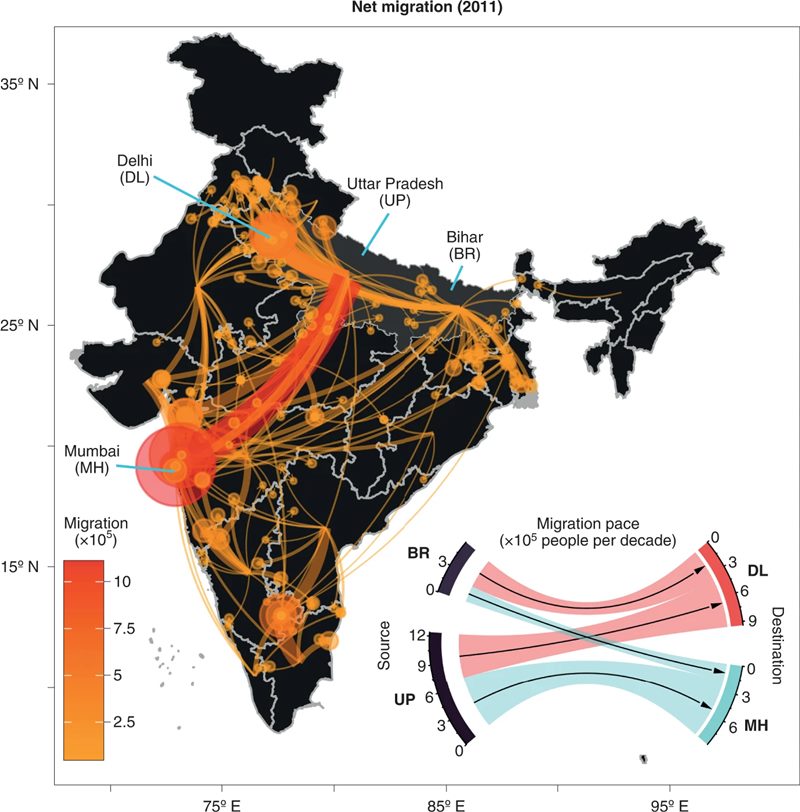

Meanwhile, the study also highlighted a major chunk of the migrant workers are from the low-income agrarian states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Also Read: How ‘uncontrolled, unplanned’ irrigation in northern India affects monsoon rainfall?

Researchers warned that the pace of migration from these regions is largely driven by socioeconomic factors. It has intensified during the recent decade and this trend is likely to continue.

They also warned that increasing climate hazards in megacities is intrinsically linked to population growth. This indicates that a large influx of migrant population is expected to further the effect of heatwaves in the already densely populated megacities such as Delhi.

Map: Pattern of flow of inter-state migration based on the 2011 India census.

Present tense, future imperfect

While this important study was published yesterday, the same day a press conference titled ‘No Country for Migrant Workers?’ was organised by Stranded Workers Action Network (SWAN), an informal network, which highlighted the distress of migrant and informal workers during the second wave of the COVID19 pandemic and lockdowns in India.

Migrant workers strongly demanded better job opportunities in their home states so that they do not have to move to megacities such as Mumbai and Delhi.

Speaking about hardships and availability of jobs for women migrant workers in native states, Jharkhand based Sima, who was trained as a frontline health worker under the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana and has been looking for employment opportunities said: “Government should make sure that women are able to find jobs in their own states, their own blocks and clusters, based on skills and technical training.”

The migrant workers also pointed out that sudden announcements of lockdowns leave them anxious causing mental health trauma. They highlighted anxiety over a possible third wave and the uncertainty in a subsequent lockdown.

A report published by SWAN last month on June 16 also highlighted their struggles of survival in cities. After COVID19 induced lockdowns and restrictions were imposed this year, nearly half (47 per cent) of informal workers did not receive their full wages or were paid only partial wages, found the SWAN survey.

Also Read: ‘Almost 50% informal workers didn’t receive full wages in the second wave lockdowns’

Wages apart, these migrant workers also reported facing food shortage due to the lockdown and loss of work. The SWAN report pointed out that 57 per cent of these workers had less than two days of rations left when they were interviewed.

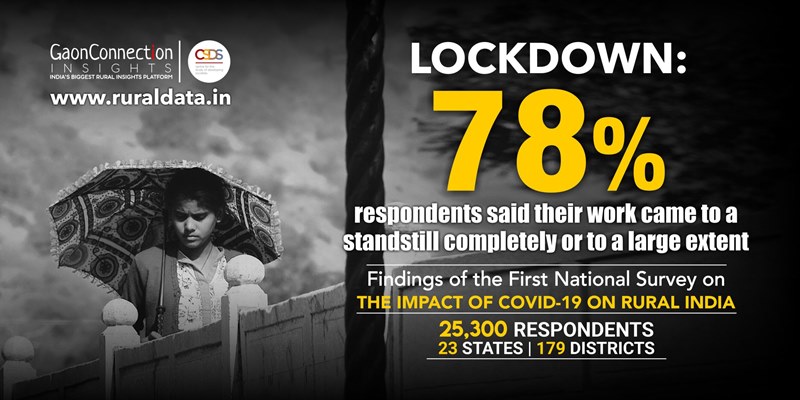

Last summer, Gaon Connection, India’s biggest rural communications and insights platform, conducted a nationwide survey across 20 states and three union territories.

The survey found eight out of 10 people did not have any work during the lockdown last year. The livelihood of 78 per cent of respondents was affected to a great degree. At least 92 per cent of rural poor households faced difficulty in accessing food during the lockdown.

Also Read: 80% rural respondents said their work was affected due to the lockdown

Last year, the country witnessed a mass reverse exodus of migrant labourers from the cities as they clambered onto buses, trains and even walked thousands of kilometres back home, penniless, braving heat, hunger, thirst and disease. In his written reply to the parliament last September, Santosh Kumar Gangwar, Minister of State for Labour and Employment, had said that amid the lockdown, more than 10 million (10,466,152 to be exact) workers returned to their hometowns.

During last year’s lockdown, 1,500,612 migrant labourers returned to Bihar, according to central government data.