Our godowns are full. Where are we going to keep our stock until the new ones are built?

By April 2020, India will have two-and-half-times more wheat and rice stock than required and our godowns are almost full already. Though the government has talked about building more warehouses, it hasn’t set a date yet. This is going to worsen the plight of our farmers

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has announced a 16-point formula for farmers in the Budget 2020-21. This 16-point formula also mentions building warehouses and setting up a cold storage chain. The finance minister said the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) shall build these new warehouses and the Public-Private Partnership model will be adopted to increase their number. It has been proposed to set up a storehouse at every block level.

It is not the first time that the Narendra Modi government is acting towards capacity build-up. In 2017, it had announced to set up 100 lakh tonnes of steel silos through Public-Private Partnership, but by May 31, 2019, the government could build steel silos worth 6.75 lakh tonnes capacity only. The government has made steel silos having a capacity of 4.5 lakh tonnes in Madhya Pradesh and 2.25 lakh tonnes in Punjab.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said that these godowns would be constructed with the help of NABARD, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and the Central Warehousing Corporation, but the existing godowns are in a bad conditions While the procurement of paddy is going on, the wheat crop will start showing up at the mandis (wholesale markets) from the last week of March.

By April 2020, India will have two-and-a-half-times more wheat and rice stocks than required and our godowns are almost filled already. This would worsen the farmers’ plight. Though the government has talked about building godowns, there is no mention of how long it will take and by when the target set would be met.

Why are warehouses and cold storages necessary?

According to a report by the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry (ASSOCHAM), the cold storage capacity in the country is very low due to which only 11 per cent of the perishable yield is preserved.

India is the world’s largest milk producer and the second largest-fruit, vegetable producing country, but it is surprising that from 40 to 50 per cent of its total yield running into crores of rupees gets spoiled.

DS Rawat, former general secretary of the institution, mentioned in the ASSOCHAM report: “India has a very poor number of cold storages. So, the crops that are damaged quickly are not able to be stored. We have the capacity to store 30.11 million tonnes of yield.”

He added: “Lack of adequate infrastructure, lack of trained personnel, use of outdated technology and inadequate power supply are hampering the way of cold storage.” The report says that 60 per cent of cold storages are in Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Gujarat.

SK Chauhan, food industry development officer at the National Centre for Cold Chain Development, Uttar Pradesh told Gaon Connection over the phone: “If we talk about Uttar Pradesh, here we have enough cold storage for potato, but there is no provision for other perishable crops. Although the government has told so in the Budget, it is to be seen how it (the capacity) is increased. There is a need to build a large number of cold storages for other crops.”

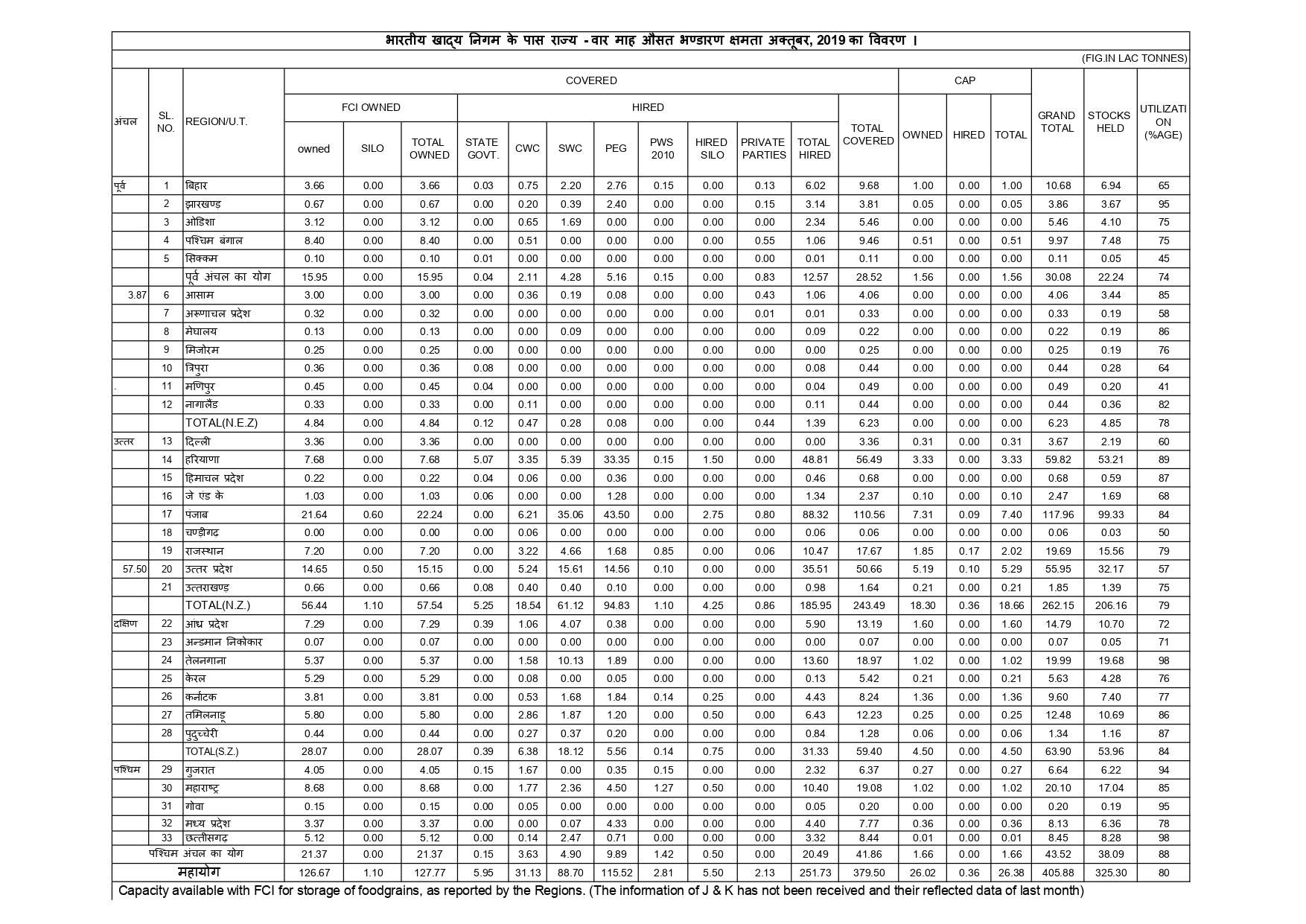

View the chart above. The report is for up to October 2019. According to this, the godowns of Chhattisgarh and Telangana are up to 98 per cent full, while the godowns in Haryana have only 11 per cent space left. The godowns in Punjab have also filled up to 84 per cent.

Due to the lack of adequate cold storage and godowns in the country, both the government and the farmers suffer losses. Last year, when the price of onion had reached Rs 200 per kilo, the government decided to buy onion from other countries. The government imports onions at a premium price, but by then the crops of individual states have already come into the market due to which they refuse to buy onions from the Centre. Thereafter, the government is forced to export the same onion at a lower price because we do not have adequate provision for keeping it. There have also been numerous reports of onion rotting away.

This year, the biggest challenge in front of the government will be to protect wheat and paddy.

As per the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) 2013, 23 per cent of the total cultivation in India was of paddy, while 16 per cent of it was wheat. Together the two crops contribute about 40% of the total agricultural yield India.

Besides, 59 per cent of the agricultural households in the country are supported by paddy cultivation while 39 per cent are with wheat cultivation at different times. If there is no place to store paddy and wheat, it is obvious that the government would reduce its procurement. Perhaps that is why there was a rife between the Center and the Chhattisgarh government about the procurement of paddy while the Haryana government stopped procuring paddy without any notification.

Sukaran Pal, a farmer living in Shahjanpur village in Garanda district of Haryana, is very distressed. He planted paddy in 13 acres this year. He told Gaon Connection over the phone: “The government was procuring paddy at the rate of Rs 1,750 per quintal. I was able to sell half the produce when they refused to take my paddy at the procurement centres. I waited for a few days and then sold paddy to the traders at Rs 1,500 per quintal.”

He added: “We have to face the losses anyhow. It was thought that the rate would be of some benefit, but nothing of the sort has happened. We are also being told to reduce paddy cultivation.”

The Food Corporation of India (FCI) has framed a regulation for the storage of wheat and rice at different times, also known as buffer norms. As per the regulation, the FCI should have a maximum stock of 214 lakh metric tonnes on January 1, 2020. But the total stock of the central pool had reached 565.11 lakh metric tonnes as on January 1, 2020, i.e., about two-and-a-half times more than stipulated. The stock of rice should be 56.10 lakh MT and is 237.15 lakh MT, similarly, the wheat stock should be 108 lakh MT which has gone up to 327.96 lakh MT.

The farmers of Punjab may be most severely hit due to this because Punjab is far ahead in the cultivation of both paddy and wheat. Punjab remains the number one state across the country by producing 40.4 quintal paddy in one hectare of farmland. But the Cost and Prices Commission report says that the spurt in paddy cultivation in Punjab is worrying.

Rice productivity in Punjab grew by 2.8 per cent between 2009 and 2013 as compared to a 37.2 per cent increase in rice production between 2013 and 2018. The state produces 11.4% of the country’s total rice output.

The FCI has procured 108 lakh MTs of paddy from Punjab till January 2020 for kharif season year 2019-20. Haryana stands second with 43 lakh MTs. In kharif season 2018-19, the FCI had procured 113.34 lakh metric tonnes of paddy from Punjab.

As per the FCI report, the highest stock of paddy and wheat is in Punjab godowns. As of January 1, 2020, Punjab has 195.38 lakh MT, Haryana godowns 104.70 lakh MT, Madhya Pradesh 77.63 lakh MT of food grains.

The Food Corporation of India’s June 2019 report shows that the stock is already more than the storage capacity. It means that when wheat inflow begins, there will be no place to keep it in our godowns.

As on June 1, 2019, the FCI and state government agencies have a storage capacity of 878.55 million tonnes with a cap of 133.55 million tonnes. The total storage capacity of the FCI is 407.31 million tonnes.

The total storage of foodgrains in Punjab is 253.89 million tonnes while the state has a storage capacity of 234.51 million tonnes. In such a situation, the question arises as to where the surplus food grains are kept and in which condition. This is an example of a single state.

However, the government maintains that the grains kept in the open are also safe. VK Srikandan and Rajendra Agarwal asked the government a question in this context in the Lok Sabha on July 16, 2019. Then, on behalf of the government, the Minister of State for Food and Public Distribution, Danve Raosaheb Dadarao, had responded.

He has said: “The foodgrains procured for the central pool and available in the FCI are stored scientifically with the treatment of pesticides in covered godowns. In spite of all precautions, certain quantities of foodgrains become non-usable due to various reasons such as natural calamities, loss during transportation. Out of the 1,165 tonnes of damaged (defective) kept in the FCI, only 15 tonnes of foodgrains are a year old while 1,150 tonnes of foodgrains are less than one year old.”

An FCI official said told Gaon Connection on the condition of anonymity: “There was never so much stock before, but this time, the situation has deteriorated. On July 1, 2016, the Central pool had 495.95 million tonnes of grain which had reached at the record level of 533.19 in July 2017. The stock reached 650.53 million tonnes on July 1, 2018, and 742.52 million tonnes by July 1, 2019.”

The official said that it was for the first time that so much grain has been lying in the stock over the past few years. The FCI data shows that on July 1, 2016, the Central Pool (Storage) had a stock of 495.95 million tonnes of foodgrains, which was recorded at 533.19 million in July 1, 2017. Similarly, on July 1, 2018, it reached 650.53 million tonnes and 742.52 million tonnes on July 1, 2019. The procurement of rice has begun, but our godowns have become almost full. Rice can’t be kept in the open and there is no visible strategy on where to keep it.

On November 19, 2019, Dulali Chandra Goswami, a Member of Parliament from Katihar in Bihar, had asked the government why large quantities of onion, tomato, potato, wheat, maize, paddy and pulses are wasted every year due to inadequate storage capacity in the country, which is causing losses to the farmers too.

The Minister of State for Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Danve Raosaheb Dadarao, had responded on behalf of the government and said: “There is no specific assessment of wastage of agricultural products every year due to lack of storage capacity. However, a study was conducted in 2015 on the quantum of central harvesting under the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and loss of post-harvest losses.”

“The report says that the yield of onion, tomato, potato, wheat, maize, paddy and dal is damaged by 4.65 to 12.44 per cent after harvesting. The government has 8,038 cold storage with a capacity of 36.77 million metric tonnes. In addition, central warehousing corporation and state agencies (government and hired) have a total storage capacity of 753.93 lakh MT (up to 30-09-2019),” he added.

Total foodgrains in the central pool by January 2020.