‘Compulsory food fortification is wasteful, ineffective and potentially harmful to human health’

While the Indian government has proposed compulsory fortification of rice with iron under its PDS and mid-day meal schemes, public health and nutrition experts warn that unnecessary food fortification can do more harm than good. A new research paper offers a word of caution.

Experts pointed out how fortification adds another intake layer of a chemical iron through fortified foods believing it may do good. Photo: Unicef India

The Indian government is on course to adopt a policy for mandatory fortification of foods, including rice, in its social safety network programmes such as the public distribution system (PDS). It is also proposed to include fortified rice in the mid-day meal scheme of the central government. Fortification of rice with iron is a significant public health response to address anaemia and malnutrition in the country, claims the government.

However, public health and nutrition experts claim that unnecessary fortification of food with excess micronutrients such as iron may do more harm than good.

A new research paper, ‘Perspective: When the cure might become the malady: the layering of multiple interventions with mandatory micronutrient fortification of foods in India’, released today on July 30, claims that this intervention of food fortification is ‘wasteful, ineffective and potentially harmful’ to human health.

In a webinar organised today, authors of the research paper shared their findings and discussed risks of ‘unnecessary’ food fortification. Anura Kurpad, the lead author, and Harshpal Singh Sachdev, another key author of the paper, argued that micronutrients are beneficial in the right dose, but potentially harmful when ingested in excess. This is similar to excessive unnecessary intake of medicines, the authors said. Kurpad is former head of the Department of Physiology at St John’s Medical College based in Karnataka. Sachdev is a senior consultant in Pediatrics and Clinical Epidemiology at Sitaram Bhartia Institute of Science and Research, New Delhi.

The authors pointed out how fortification adds another intake layer of a chemical iron through fortified foods believing it may do good. This is in addition to the ongoing pharmacological iron supplementation as well as other voluntary iron fortifications, such as those of salt and manufactured food products.

‘Supplying more’ by layering multiple nutrient interventions, instead of ‘doing it right’, without thoughtful considerations of social, biological, and ethics frameworks could be counterproductive, pointed out the experts. “The cure, then, might well become the malady.”

Is fortification harmful?

During the webinar today, at least 18 Indian nutrition, health, and epidemiology experts argued for “extreme caution” in implementing new chemical interventions to address micronutrient deficiencies in India.

As a significant percentage of the population continues to suffer from malnutrition and anaemia, India is considering compulsory fortification of rice from 2024.

The case in point is the mandatory iron fortification of the rice to be provided in the national programmes of ICDS (Integrated Child Development Services) and mid-day meal schemes.

Besides, as part of the ICDS, pregnant women are already given iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets to prevent nutritional anaemia. This forms an integral part of the safe-motherhood services as part of the Reproductive and Child Health Programme. The programme recommends pregnant women to consume 100 tablets of iron and folic acid during pregnancy.

Public health and nutrition experts pointed out that women who have been consuming iron in excess can have adverse effects on fetal development and birth outcomes, with adverse modifications of the healthy microbiome, and increased risk of chronic diseases. “Since the intervention of iron or fortification is not being monitored, no evidence is generated on its benefit or safety; such a policy is not justified,” reads the press statement issued today.

Also Read: To fortify milk, or not to fortify … the debate goes on

Rs 26 billion ‘wasted’ annually on fortification

In India, fortification has been made mandatory for some micronutrients. Last year, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) considered it mandatory to fortify edible oil with vitamin A and D ‘so that people of India can enjoy better immunity with good health’.

However, earlier the choice for whether to fortify or not was dependent on the stakeholders, it was voluntary.

The experts also warned that this policy is a ‘wasteful’ expenditure of more than Rs 2,600 crore (Rs 26 billion) annually on fortification of rice with iron in an attempt to reduce anaemia in India.

Also Read: ‘Rice and wheat in India are lot less nutritious than they were 50 years ago’

“The money would be better spent on alternative diet based sustainable solutions and improving the access to quality health care in the public sector,” said Harshpal Singh Sachdev.

The publication also highlighted that this fortification policy ignores the role of a balanced and diverse diet for addressing the variety of nutritional problems. The policy is proposed in addition to the ‘supplementary iron’ being given through the government programmes.

The experts revealed that increasing the iron intake alone has no impact and cannot replace dietary diversity. It is the dietary diversity that facilitates the uptake of iron for the body.

40% adolescent girls in India anaemic

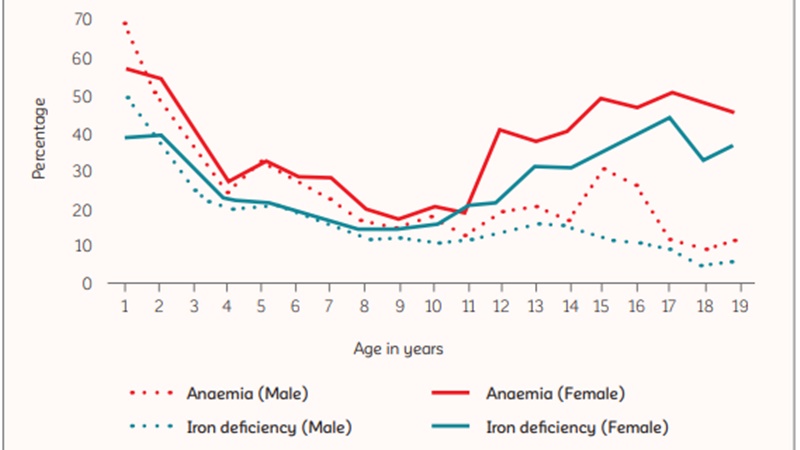

According to the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey, 2016-18, 40 per cent of female adolescents in the country have anaemia.

Graph: Prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency by sex among children and adolescents aged 1–19 years, India.

The recently released National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-20, shows the prevalence of anaemia among children under five years of age has increased in 18 out of 22 states and Union Territories. A similar trend was seen in the prevalence of anaemia among women in the age of 15-49 years. Out of the 22 states/UTs, 16 showed an increase in anaemia among women.

Anaemia, which results from a lack of red blood cells or dysfunctional red blood cells in the body, leads to reduced oxygen flow to the body’s organs. Its symptoms include fatigue, weakness, dizziness and shortness of breath, among others.

According to the World Health Organization, the most common causes of anaemia include nutritional deficiencies, particularly iron deficiency, though deficiencies in folate, vitamins B12 and A are also important causes. Iron supplements can be used for iron deficiency.

And hence, the fortification.

Experts question anaemia prevalence

According to Anura Kurpad, the lead author, “The prevalence of anaemia is magnified because of the use of inappropriate haemoglobin cut-offs to diagnose the malady in children and pregnant women.”

In the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey, anaemia was assessed based on haemoglobin concentration obtained from venous whole blood.

Kurpad highlighted the current method of measurement of haemoglobin inflates anemia prevalence. “In the surveys, haemoglobin values are measured through capillary blood rather than the venous blood, which is fallacious, since the haemoglobin concentration in these two samples can differ by as much as 1 g/dL. This in fact creates much more potential for misclassification when the population has an average haemoglobin value that is close to the diagnostic cut-off for anaemia,” he explained.

“It creates an ongoing perception of a stagnant or worsening anaemia prevalence, however, it does not reflect the true nutritional status of a population,” the lead author added. This indicated that the cure proposed may not even make any impact on their (magnified) status of micronutrient deficiency.

During the webinar, the experts also highlighted that “food fortification with micronutrients is particularly attractive to policy makers, industry, and implementation agencies, primarily because it is thought to require no behavioral modification by the beneficiary, but also because it is safer and less expensive than direct supplementation.”

Vitamin C fortified rice in Odisha

Last year, the Odisha government decided to distribute vitamin C fortified rice in Malkangiri district, a tribal-dominated district of the state that is notorious for high malnutrition. This was done to reduce malnutrition and anaemia.

However, the decision received criticism from several food experts, and activists, who defined the move as ‘a travesty of food justice and mockery of food security to the tribal population’. They believed micronutrients should be given as a supplement and food should be kept separate.