Active tribal community participation facilitates the vaccination process in Karnataka’s Chamarajanagar

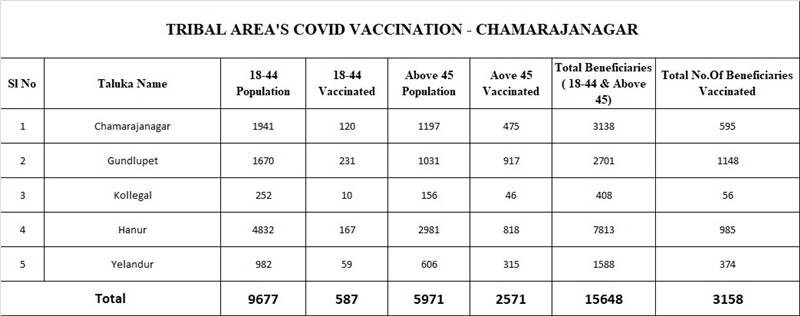

In a welcome move, the tribal communities in Chamarajanagar district in Karnataka along with the district administration, non profits, researchers and citizen volunteers take the COVID19 vaccination drive forward. Of the 15,648 eligible-for-vaccine tribal inhabitants, 3,158 have been inoculated.

Those driving the COVID19 awareness and vaccination initiatives in Chamarajanagar, about 175 km from state capital Bengaluru, believe that coercion, intimidation and ultimatums are not going to work here. All photos: By Arrangement

The ‘othering’ of tribal communities is not going down well in Chamarajanagar district in Karnataka. There is impatience amongst the communities, health workers and non-profits working in the area for the cliched reasons being trotted out for vaccine hesitancy — superstition, lack of education, fear…

According to Prashanth Srinivas, Assistant Director (Research), Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru, at the field station in BR Hills, Chamarajanagar, the tribal communities are cautious. The vaccination strategy, so well adapted to the privileged urban middle class, is hardly suitable to their settings, and no one seemed to notice that, he told Gaon Connection.

He recounted how a Soliga village elder asked him, ‘How come nobody came to my doorstep when I asked for piped water and roads, but today everyone is lined up to save my life?’ The Soliga leader also added, ‘Wasn’t my life important before your city people’s illness came to our forests?’

Also Read: In the Nilgiris, local NGOs roped in to vaccinate tribal communities at their doorstep

Working together

“Building trust and confidence is the first step if the vaccination drive has to be a success,” Srinivas said.

Those driving the COVID19 awareness and vaccination initiatives in Chamarajanagar, about 175 km from state capital Bengaluru, agree that coercion, intimidation and ultimatums are not going to work here. According to Srinivas, in a welcome move, all the stakeholders are working in tandem. “What was a pleasant surprise was that the district administration welcomed and sought the help of NGOs, volunteers, the tribal sanghas…,” he added.

Reaching vaccines and awareness to hamlets in the remote areas of the densely forested Biligirirangana Hills, or BR Hills for short, was challenging.

BR Hills is part of both the Western and the Eastern Ghats and fall in Chamarajanagar district. Several tribal communities, predominantly the Soligas, live there and across the five talukas or blocks of the district, most of which is densely forested.

According to data from the district administration, there are 23,182 tribal people in Chamarajanagar district, of which most belong to the Soliga community. The others include the Kadu Kuruba and the Jenu Kuruba tribes.

“People have to travel long distances through forests to the PHCs (Primary Health Centres) and they will not do that. In many places there are no roads nor any transport,” C Made Gowda, secretary, Zilla Budakattu Girijana Abhivruddhi Sangha, a federated collective of the Soliga Adivasi people in Chamarajanagar, told Gaon Connection. So the vaccination teams go to the villages.

Also Read: Uttarakhand faces an uphill task as it tries to reach vaccines to its far flung villages

Continuous conversations on vaccine awareness

“There is vaccine hesitancy, especially in the remote areas, but we are making headway,” Made Gowda added. Gowda holds a Phd in Social Work from the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bengaluru, and is a grassroots leader of the community.

“When we reach a village, we gather a crowd around us. Men and women are encouraged to ask questions, clear their doubts and we show them charts about the virus, how it is transmitted and so on,” Madevi Kumbegowda, a 40-year-old field supervisor from the Bengaluru-based Institute of Public Health Research Centre stationed at Erakannagaddepudu, BR Hill,s about 35 kilometres from Chamarajanagar, told Gaon Connection.

As a Soliga herself, Kumbegowda has had a lot of traction with her fellow Soligas. Every day, she travels to villages with a team of four or five health care workers to talk to them about the importance of getting vaccinated. Three mobile health units of the Tribal Welfare department make the journey to the remote villages.

“Mobilising communities gained the vaccination drive more traction and momentum,” Tanya Seshadri, Director, Tribal Health Resource Centre, Vivekananda Girijana Kalyana Kendra (VGKK), BR Hills, told Gaon Connection.

Also Read: Devolving more powers to elected panchayat representatives can help combat the pandemic effectively

The Kendra has been working for and with the tribal people for four decades and it set up the Karuna Trust that began to help implement government programmes and work in difficult-to-reach or politically neglected communities. It has done significant work in health and education.

Covid crisis in the hills

In the first wave, BR Hills was the last green zone that remained largely untouched by the coronavirus. There were not many cases, and certainly not in the more remote villages. “We expected the second wave to be like the first one and were more worried about the consequences of the lockdown than the coronavirus,” Seshadri said.

“But, the Institute of Public Health Bengaluru, several NGOs and citizen volunteers rallied together and offered our services to the administration and it welcomed us in ways we did not expect,” Seshadri said.

A multi-pronged approach was adopted, she explained.

In association with the zila panchayat, a COVID Seva Kendra was set up at a tribal residential school at Jeergegadde village in Hanur taluk. A kitchen was set up and health workers and carers came from nearby villages to be with nearly 30 people who had tested positive and were staying there. All of them have been discharged.

“Once we set up the Covid Care Centre at a place that was familiar to the people, the hesitation in coming there came down. The Centre was in familiar territory, with known people taking care of them,” Harshal Bhoyar, chief executive officer, Zila Panchayat, Chamarajanagar. He reiterated how decentralised solutions have worked well in the district, particularly amongst the tribal communities.

Also Read: Addressing vaccine hesitancy in rural India, one jab at a time

“Tribal leaders came on board and automatically the testing improved and the confidence went up,” he pointed out.

According to Bhoyar, one of the main reasons there were hitches was the fact that many in the tribal communities were unable to navigate the system of going to PHCs, registering their names and so on.

Partnering with the community was the best way forward, reiterated Seshadri.

“We also requested the social welfare department to identify the adivasi communities as vulnerable and treat them as priority groups,” she said. With Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement on June 7 to open up vaccinations for the 18 and above age group, the momentum has picked up.

There have been concerted efforts to keep conversations around vaccines going. Repeated trips are made to villages, doubts are cleared and there is never any coercion involved, Seshadri said.

Also Read: Can Tamil Nadu’s robust public health system control the second wave?

“WhatsApp misinformation reached places before health workers could,” laughed Seshadri. As a result there are also fears of dying from vaccines, or, in the case of men, apprehensions of impotence, she said.

The district machinery, nonprofits and volunteers are focussing on positive stories. Rather than striking fear and alarm, they are talking about the benefits of getting vaccinated.

In order to streamline the process, the 148 tribal hamlets across Chamarajanagar have been divided into 14 clusters. “We have begun cluster-level leader meetings and identified men and women who will volunteer from there,” explained Seshadri. She also pointed out how conferring, discussing and coming together for conversations before taking any decision was the socio-cultural practice of the Soligas.

“The community has always functioned this way. No opinion is dismissed, no question considered insignificant or silly. It is time-tested and successful, and we are following the same approach,” Seshadri said.

Also Read: ‘Trust deficit in health facilities a major hurdle in tackling COVID19 in rural, tribal areas’

The workforce also uses traditional ways of communication such as storytelling, song, dance and drama to convey messages about COVID 19 and the vaccines through cultural troops that have been formed.

“If the vaccine supply is steady and regular, we can build on the momentum. Sometimes just as inoculations pick up the tempo, the supply stops and the numbers drop,” Bhoyar added.

Sharing the district administration’s latest data on the vaccines administered in the five talukas of the district so far, he told Gaon Connection that, of the 15,648 eligible tribal beneficiaries in the district, 3,158 had already been vaccinated (this included 587 people in the 18-44 age group and 2,571 people in the above-45 category).