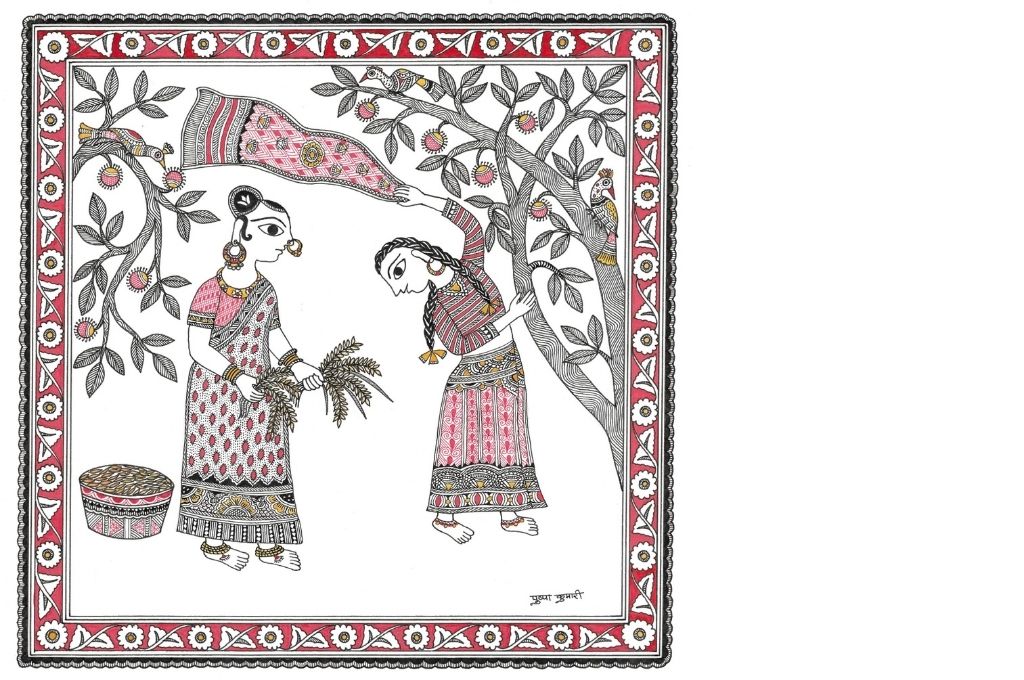

Life As Art: Madhubani paintings depict how a women’s SHG saved Odisha’s Kanjariguda

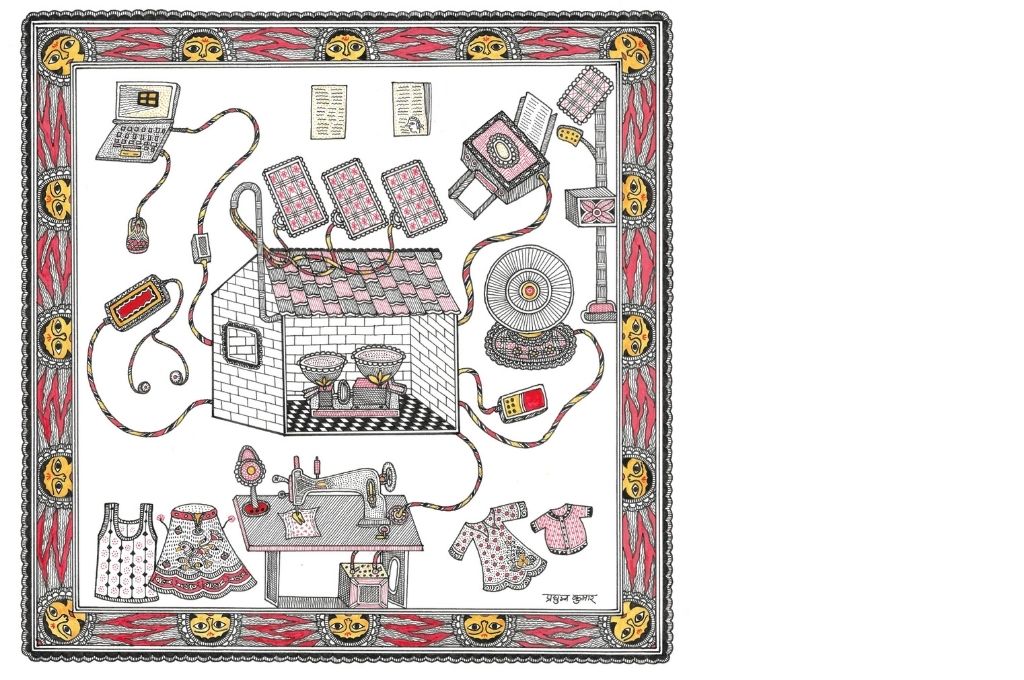

In 2019, a women’s self-help group (SHG) established a decentralised rice and millet milling centre in Kanjariguda, boosting household incomes. This helped more than 500 paddy and 270 ragi farmers access a mill. See, through Madhubani paintings, the various gadgets powered by this effort.

Pradyumna Kumar and Pushpa Kumari

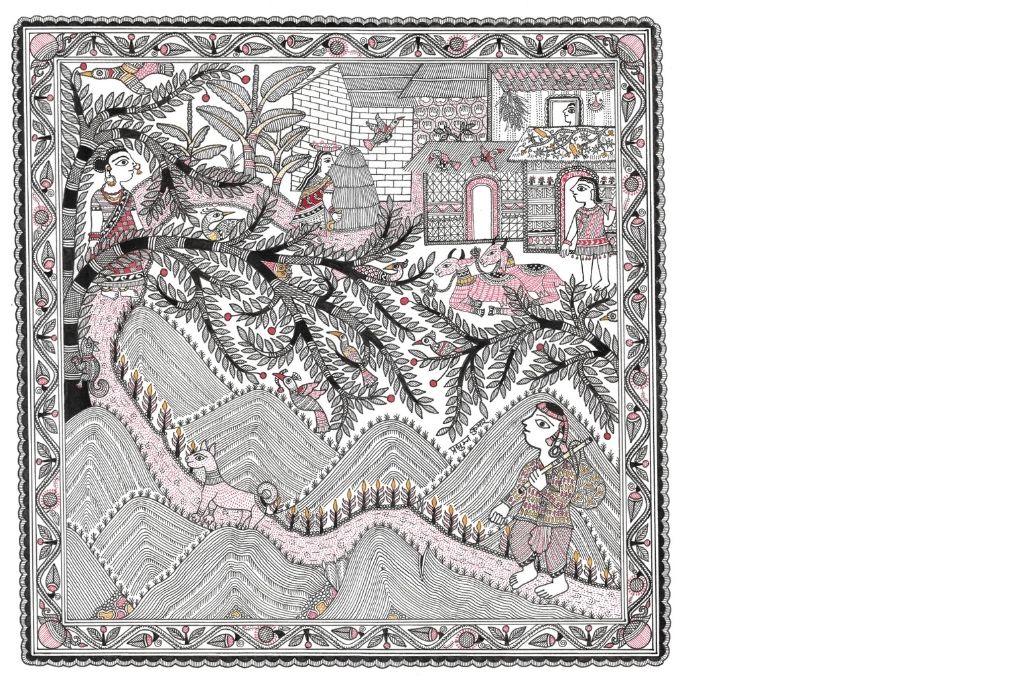

In Koraput district, Odisha, lies a remote village called Kanjariguda, home to an Adivasi community of farmers who predominantly grow ragi and rice. The village is so remote that villagers have to walk several kilometres, across forests and mountains, to hull their rice or access basic services such as mobile charging, photocopying, or printing.

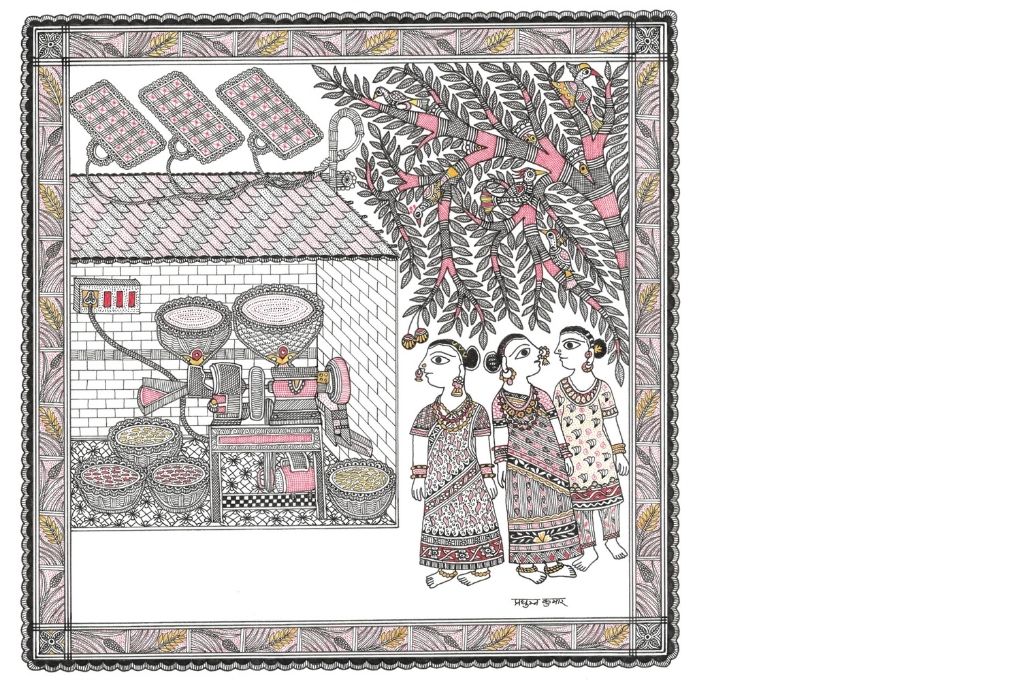

In 2019, a women’s self-help group (SHG) established a decentralised rice and millet milling centre in Kanjariguda. This eased the drudgery that came with a lack of access to a mill, for more than 500 rice farmers and 270 ragi farmers. Earlier, they had to spend much more time and money to get basic work done. Now, the income generated by the centre is equally divided amongst the SHG members.

Apart from milling, the centre also offers other essential services such as printing and mobile charging—services that are in high demand as they are needed for school work, government documentation, and other purposes. Everything at the centre is powered by solar energy.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, Kanjariguda went into a strict lockdown, alongside other villages in the district. Later, when shops began to open up, the disruptive power cuts and lack of access to diesel (for those reliant on generators) made it difficult to get work done.

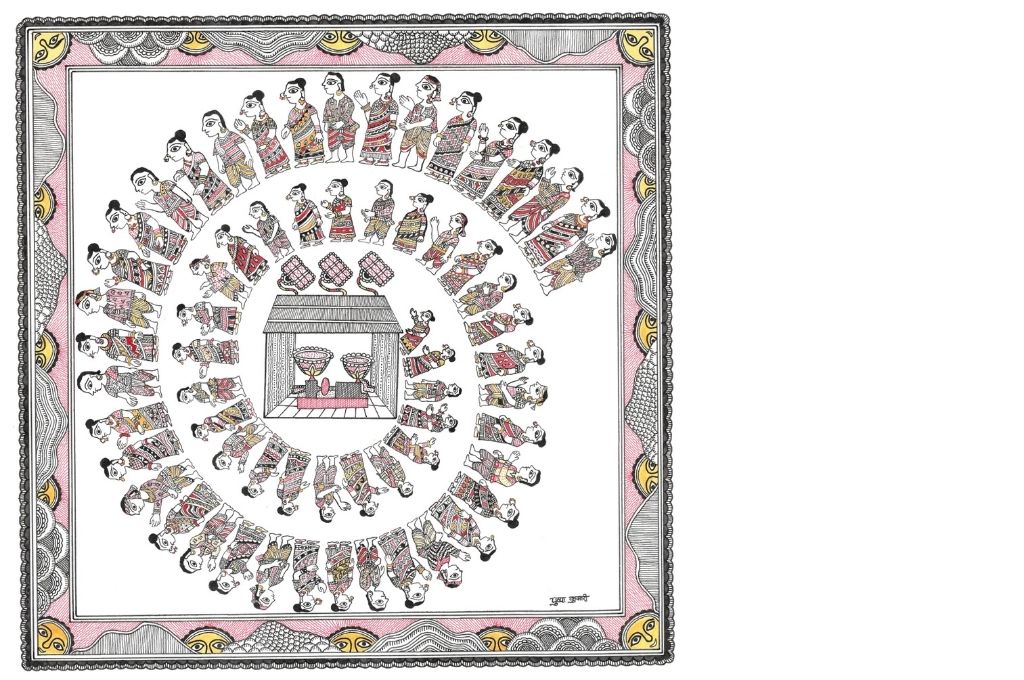

So, local nonprofits took it upon themselves to spread news of the functional solar-powered centre to nearby villages. Within a few weeks, people from 17 villages in a 12-15 km radius began coming to the centre for essential services. This increased the mill’s demand and income, helping farmers in these uncertain times.

Solar-powered equipment (in an area that experiences frequent and long power cuts) made the centre seem reliable. New customers, recognising its convenience, continue to use it even post-lockdown.

Rajani Jani, the president of the SHG and Rai Jani, its secretary, say, “Farmers get milling services within a very short distance. We have been moving from village to village to share information about our milling machine. Spreading the message this way has been very effective in promoting our business. Ragi is very nutritious—especially for young children, as well as pregnant and lactating women. We plan to start sale of ragi powder to the nearby anganwadi centres, to ensure a supply of nutritious food for the children.”

One of the biggest challenges going forward, for entrepreneurs from poor households and those who are restarting their businesses, will be their ability to take risks. Decentralised livelihood models (driven by sustainable energy) that build on existing local institutions like SHGs allow for risk to be shared, while also benefitting the whole community.

This story was sourced from a campaign by SELCO Foundation and IKEA Foundation called ‘Let’s Rise Up’. It was originally published in India Development Review. You can read the story here.