Once an integral part of rural households, cattle are now conspicuous by their absence. Will they return to revive the rural economy?

While the cattle population and milk production in the country are rising, paradoxically, in India’s villages, cattle that were integral to people’s homes, are disappearing. This has impacted rural livelihoods, soil fertility, health and economy. Gaon Connection travelled across several villages to understand what happened to the family-owned cows and buffaloes.

Shahjahanpur/Sitapur/Bareilly/Badaun (Uttar Pradesh)

Ram Prasad has been gram pradhan (village head) of Lakshmanpur village for over 15 years. Born and brought up in the village in Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh, 50-year-old Prasad has watched the landscape of Lakshmanpur change beyond recognition.

He misses the musical sound of gai-bail ki ghanti (cattle bells) that once rang across his village.

“In my childhood there was enough grazing grass on either side of the banks of river Kathina. People brought their cattle there to graze. Not any more,” the gram pradhan told Gaon Connection as he sat under a mango tree reminiscing about old times.

“The number of cattle in our village has shrunk. From nearly thousand heads of cattle in the village some 15-20 years ago, there are just about three hundred or so now,” Prasad lamented. Those may also disappear soon, he feared.

It is a paradox. On the one hand, both cattle population and milk production in the country are rising, but on the other, rural households that once always had cattle, no longer do.

The concern of disappearing cattle in rural families is not limited to empty cattle pens alone. It has a direct impact on rural agriculture, rural economy and also the health of rural citizens who regularly consumed milk, curd and ghee (clarified butter) that came from the cows at home. The impact of missing cattle is being keenly felt in the ongoing COVID19 pandemic as hunger and malnutrition raise their ugly heads in rural India.

Also Read: Rising hunger stares rural India in the face as the second wave of COVID invades villages

“It is a fallacy to think that cows are useful only as producers of milk. There are so many other ways cattle contribute to a farmer’s income and well-being, including maintaining soil fertility,” Mahesh Chandra, senior scientist with Bareilly-based Indian Veterinary Research Institute, told Gaon Connection. “Owning cattle could revive the rural economy,” he asserted.

Declining cattle in rural households

Cattle have always been an integral part of rural households. They were the protagonists of literary compositions like Munshi Premchand’s Do Bailon ki Katha or Godan. Movies set in rural India would be incomplete without cattle in the background or a pair of oxen tilling the field. Almost every rural family had cows that they named, fed and cared for.

But not anymore.

Family owned cows and oxen are fast disappearing and the cattle pens that were extensions of people’s homes, lie vacant. Where once cows and buffaloes mooed loudly and chomped noisily at the fodder, there is now only silence.

Also Read: Amul hikes the price of its milk by Rs 2 per litre — will the dairy farmers benefit?

Some 85 kilometres away from where Ram Prasad reminisced about his childhood sitting under a mango tree, Girishpal Singh Yadav looked on pensively as his five remaining cows fed from a trough.

“About a decade back, I had 10-12 cows. I had two oxen too, but not anymore,” the 70-year-old farmer and cattle rearer from Kiratpur Bihari village in Tilhar tehsil of Shahjahanpur district, told Gaon Connection.

Not too far, in Gauhapur village of Shahjahanpur, 70-year-old Nanhi Devi sat by the side of a trough that once held water for her cows. She has no cows left. “We also owned buffaloes and oxen. We had many calves. But in time, some of them died. We sold some others when my daughter got married,” she told Gaon Connection. Her younger family members have migrated to cities and there was no one to look after the cattle at home, she complained.

Rural paradox

Ironically, while cattle are fast disappearing from rural households, milk production in the country is at an all time high.

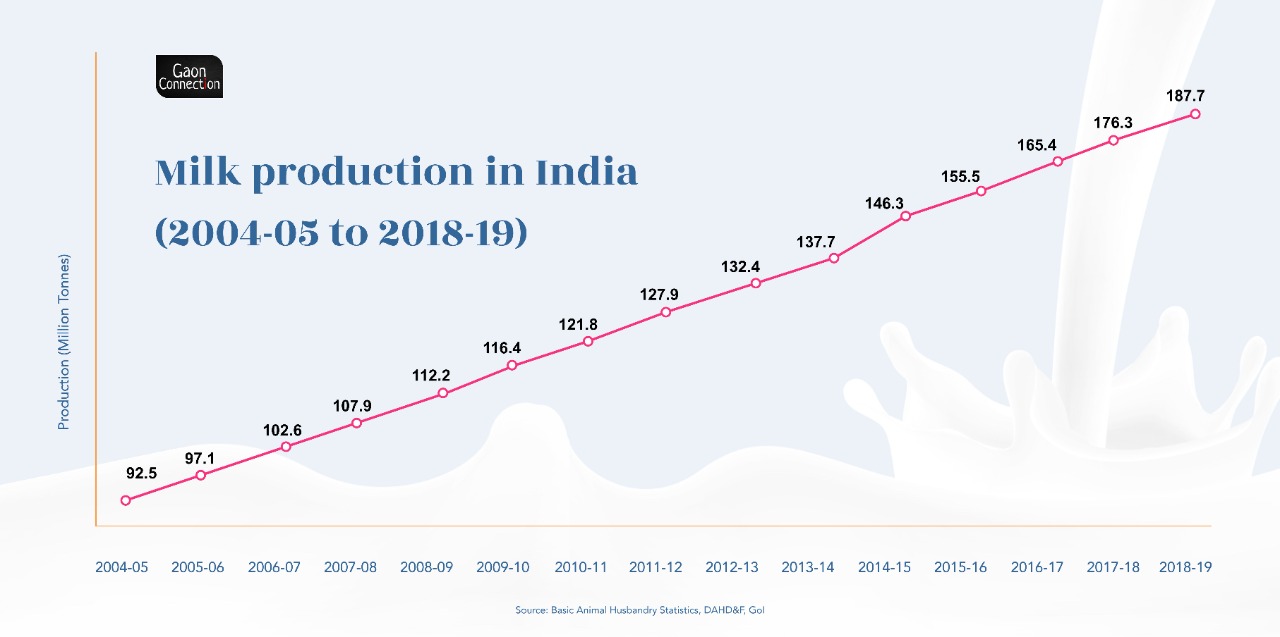

According to the National Dairy Development Board, milk production in India has increased from 55.6 million tonnes in 1991-92 to 187.7 million tonnes in 2018-19. It further jumped to 198.4 million tonnes in 2019-20. The demand for milk is expected to touch 266.5 million tonnes in 2030.

Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Punjab are considered major milk producing states in India.

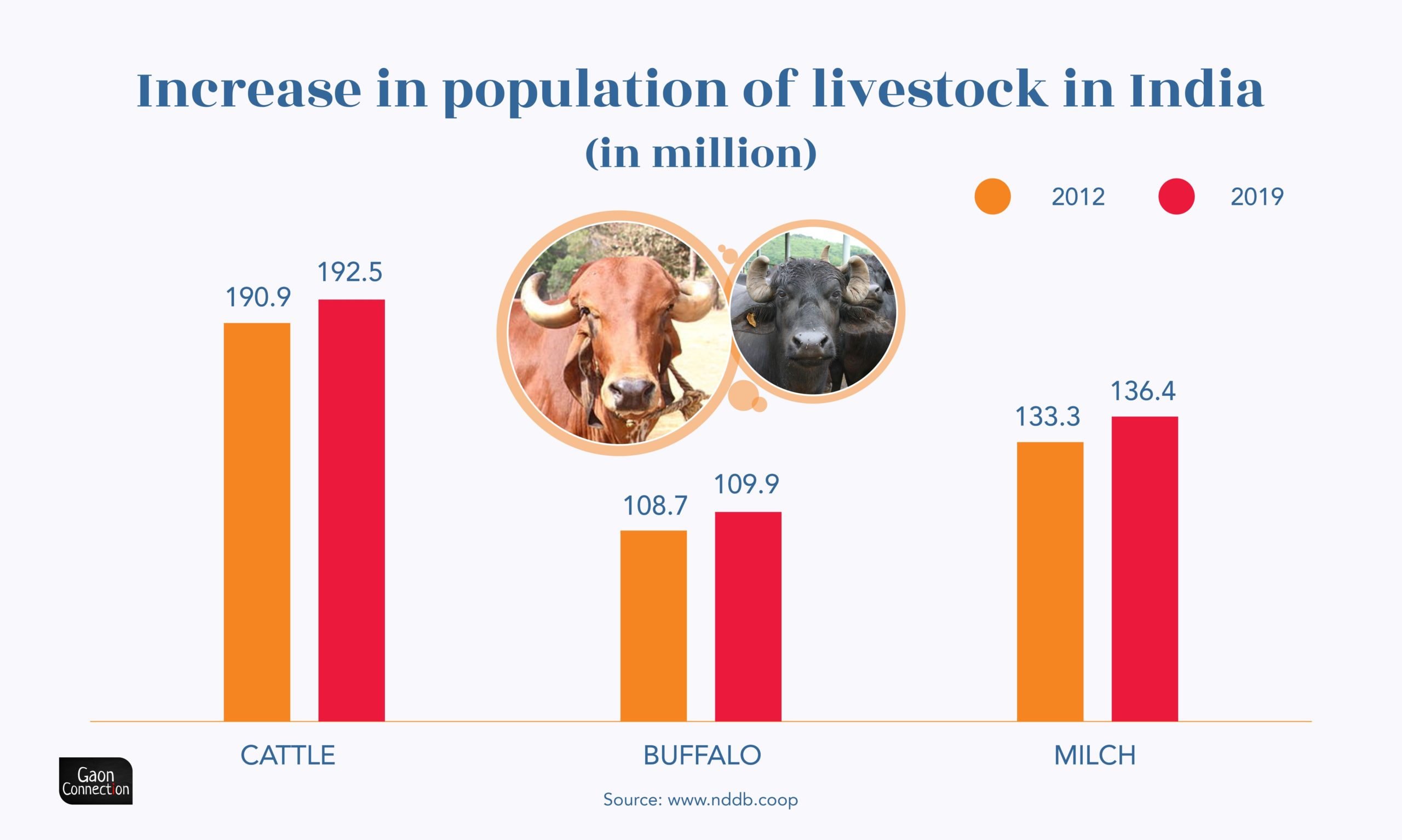

Along with milk production, the cattle population in the country is also on the rise. As per the National Dairy Development Board data, in 2012 there were 190.9 million cattle, 108.7 million buffalo and 133.3 million milch cattle in India. Their numbers increased to 192.5 million cattle, 109.9 million buffalo and 136.4 million 750 milch cattle in 2019.

But these numbers are of the mass producing milk dairies and cooperatives in the country. They hide the emptiness of vacant cattle pens in rural households and their wide reaching impact. Cattle rearing that once supported rural livelihoods and nourished rural residents is now dwindling.

Why are rural families giving up on their cattle?

Gaon Connection travelled across four districts of Uttar Pradesh — Shahjahanpur, Bareilly, Badaun and Sitapur — to speak to villagers to understand why rural households don’t rear cattle anymore. Most villagers said that the fast-changing social fabric of rural India was a big contributing factor towards disappearing cattle.

Mechanisation has brought tractors in, which leave little for the cattle to feed on, land holdings have shrunk, grazing lands are encroached, families are becoming nuclear, homes are shrinking in size, and of course, people are migrating to cities in search of jobs.

“Earlier we ploughed and prepared the field with oxen. The dung fertilised our field too,” said Girishpal Singh Yadav of Kiratpur Bihari village in Shahjahanpur. “Ever since agriculture became mechanised, and tractors came in, the oxen have become irrelevant,” he observed sadly.

According to him, the traditional methods of farming and fertilising made the grains more nutritious and tastier. “But many in the younger generation feel a sense of shame working with cattle, clearing dung, etc,” noted Girishpal Singh.

In the neighbouring district of Bareilly, Dharmendra Singh of Nagariya Nauramad village said, “At one time we kept plenty of cattle at home. I have myself ploughed the fields with oxen. But now our village has fifteen tractors, and I use a tractor too. I don’t own any oxen now.”

Also Read: Burdened by rising diesel prices and increasing irrigation cost, paddy farmers reduce their acreage

The cattle that was once considered the pride of a family and synonymous with wealth, was dwindling in importance. “Nobody wanted the cattle anymore,” 50-year-old Dharmendra Singh sighed.

Disappearing grazing lands

Jai Singh, from Khedarath village in Shahjahanpur, lamented the loss of pasture lands for the cattle. “Earlier we could take them to open fields and jungles to graze. But where are these spaces now,” the 65-year-old asked Gaon Connection.

“The biggest hurdle in rearing cattle is the cost of fodder,” Balak Ram from Galothi village in Badaun district, told Gaon Connection. “Wheat is now harvested by machines and because of that there is not much stubble left for the cattle as fodder,” he said.

Ram went on to inform that there used to be large tracts of empty lands that were open for the cattle to graze, but all of that had been either fenced in or converted into patta (private) land. “Few can afford to tie their cattle and feed them costly store-bought cattle feed,” he lamented.

Kunti Devi from Gauhapur village in Shahjahanpur had similar concerns. “Cattle can no longer roam freely as they once did in fields feeding off grass. Many of us cannot afford to keep cows tied up at home and buy fodder for them,” the 42-year-old told Gaon Connection.

Also Read: With cattle markets shut and the monsoon around the corner, Maharashtra farmers are in a fix

Villagers informed that on an average a cow would consume 10 kilogrammes (kgs) of fodder a day. A quintal (100 kgs) of fodder costs approximately Rs 500. Thus, on an average, one cow consumes fodder worth Rs 50 a day, or Rs 1,500 a month.

Kunti Devi also pointed out how fields were fenced with barbed wire these days and cattle often injured themselves, sometimes seriously. “We have to spend money on treating those wounds. Sometimes the injury is so deep that the cattle die,” she informed.

Nuclear families and bondage

The fracture of the joint family system in rural India is also a cause for the declining number of cattle. Where once resources, labour and costs were shared in extended families, now each family has to fend for its own.

“We are four brothers and we do not live together anymore. Each of us owns four buffaloes and the work is taxing,” Rajkumar Singh Chauhan, a resident of Karanpur village in Badaun, told Gaon Connection.

“There is bondage in rearing cattle. One is tied to the cattle, and that is why so many younger people are refusing to rear them,” Nathu Lal, a cattle rearer from Khedarath, told Gaon Connection. The 62-year-old said he owned nearly 17 heads of cattle.

Also Read: COVID and rural economic distress: Food for all and work for all should be the way forward

Dharmendra Singh Yadav of Nagariya Nauramad village in Bareilly echoed similar concerns. “If you want to keep cattle, there is a long list of things you have to do. Buy the cattle, buy fodder, buy straw. The price of fodder has gone up, it is non-stop expenditure,” the nearly 50-year-old farmer said.

In the neighbouring district of Shahjahanpur, 70-year-old Karan Varma from Dadraul village lamented that it is a twenty four hour job looking after cattle. “You have to feed them, bathe them, clean out the cattle pens of dung. Not everyone can do it,” he said.

Decline in cattle, decline in soil fertility

The dwindling number of cattle in villages could be a cause for concern, say agricultural scientists. The quality of soil is all important and it was these cows and buffalos and oxen that kept the soil nutritious and healthy, they say.

“Cattle are a source of wealth. Their milk can be sold for an income; they are a continuous source of fertilisers for the land,” Rajiv Kumar Pathak, from Sugarcane Research Council, Shahjahanpur, told Gaon Connection.

Also Read: ‘Soil testing as vital for crops as diagnostic tests are for humans’

“As the number of cattle in villages are decreasing, we are already seeing the effect on the lands. If farmers do not use dung as fertilisers, it is possible, not too far in the future, that more and more chemicals will have to be used that will cut down on the yield by half,” Pathak warned. The health of the soil stands to lose out if cattle are ruled out of the equation, he added.

“Farmers are increasingly dependent on chemical fertilisers, as readily available and free dung is no longer available to them,” said Balak Ram, a farmer from Galothi village in Badaun. “More importantly, milk that provided nutrition to the children is missing from their diet as many times the families in the village cannot afford to buy milk from the shops,” he told Gaon Connection.

Pramod Kumar of Manpur village in Bareilly district cannot thank the cattle population in his village enough. “We have a lot of cows, buffaloes and oxen in our village. Because so many villagers reared cattle, it softened the blow of unemployment during the pandemic. Rearing cattle was economically viable,” he told Gaon Connection. Since his village was located close to Ramganga river, he said there was plenty of fodder and water for the cattle.

In the pandemic, with things coming to a standstill, and now with the fuel prices rising almost on a daily basis, rearing cattle at household level can revive the rural economy, assert agricultural economists and agri scientists.

Reviving rural economy

Recently, on July 14, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs, chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, approved revision and realignment of schemes of the Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying to implement them as part of the special livestock sector package of Rs 98,000 million over the next five years starting from 2021-22 fiscal.

“There are a lot of entrepreneurship opportunities in raising cattle. The cattle’s urine, dung etc., are being used to make pesticides… The economy of a village depends on cattle,” insisted senior scientist Mahesh Chandra from the Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Bareilly.

According to Chandra, more and more people are moving towards organic farming and for that, cattle are essential. He acknowledged that raising cattle had become difficult and expensive. But there were so many central and state government schemes that were encouraging the farmer to own cattle, he pointed out.

Ram Kishore Ruhela, veterinary officer, Shahjahanpur, told Gaon Connection that the government was encouraging people to rear cattle at household level. “We tell them about breed improvement. The department of animal husbandry and dairying, has worked tirelessly to promote cattle rearing,” he informed.

Also Read: Severely malnourished under-5 children consumed by hunger in the pandemic

Cattle bring wealth to the village, said the veterinary officer. “Milch cattle provide villagers a livelihood through milk production, their dung is a good source of fertiliser, and they have a beneficial effect on the economy of the village and the country,” he added.

According to Ruhella, apart from cattle fairs, inoculation of the animals, there was also a programme underway to provide Aadhaar cards to the cattle.

Asked if villagers were falling out of love with their cattle and Rajkumar responded: “Someone who has reared cattle would rather go without food himself than see his cattle go hungry.”

Cattle don’t just provide companionship. Rising fuel prices do not affect their work performance in the fields; their dung enriches the lands and saves on the money spent in buying urea and chemical fertilisers; their milk nourishes families and also provides an additional income.

Will the vacant cattle pens see the return of the cattle and in turn revive the rural economy?

Written by Pankaja Srinivasan.