One in five rural households sold or mortgaged land, jewellery or valuables during the lockdown

Gaon Connection’s national rural survey found that nine out of 10 rural citizens faced some sort of financial difficulty during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Kalawati Devi, 45, from Jharkhand’s Brahmani village of Silli block, about 40 kms away from Ranchi, used to work at a brick kiln in Kolkata. Due to the nationwide lockdown in view of the COVID-19 pandemic, Kalawati, with nine of her family members, returned to her village home. They could not find any employment opportunities in the village and struggled to manage domestic expenses.

“Our utensils have all been sold. What else could have been done to fill out stomachs?” Kalawati asked. “For the past three months, we have been selling off our belongings to manage expenses. Now, however, with the beginning of paddy sowing, we have found work and started receiving some money in wages,” Kalawati told Gaon Connection.

Kalawati’s neigbour Tara Devi, 32, used to support her family by making jhadu (broom) using bamboo, but since the lockdown came into effect, the market has been closed and sales stopped. “I had to sell the tree of my courtyard, my bicycle and the goats to feed my children,” Tara said. Her children’s names have not been added to the ration card. The 10 kilos of rice she gets in ration is not sufficient for her family of six.

Kalawati and Tara Devi are not the only women in the country those were compelled to sell their belongings to feed their children during the lockdown. To understand the hardships of rural India during the lockdown, Gaon Connection, India’s largest rural media platform, conducted a first-of-its-kind national rural survey based on face-to-face detailed interviews with 25,300 respondents, carried out in 179 districts across 20 states and three union territories. The survey, showcasing the invisible casualties of the COVID-19 lockdown, was carried out by Gaon Connection Insights, Gaon Connection’s data and insights arm, and was designed and data analysed by New Delhi-based Centre for Study of Developing Societies (Lokniti-CSDS).

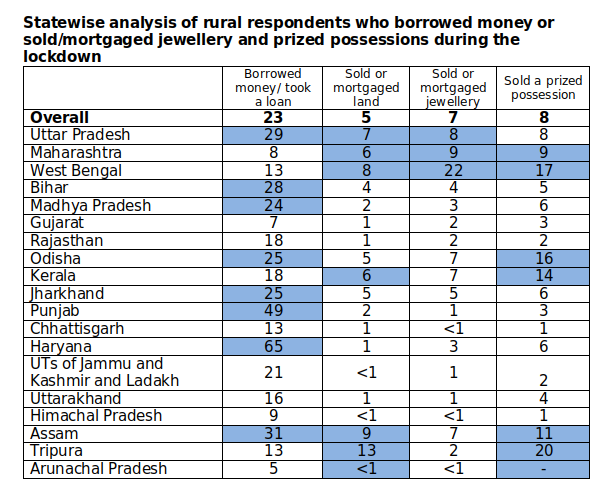

The survey found 20 per cent of the respondents said that they had to pledge or sell land, jewellery and valuables in order to tide over the lockdown. Another 23 per cent had to borrow money to meet various expenses.

“For the past 20-30 years, the Indian government has focused on the upper class and upper-middle class. They did not account for rural India while formulating the policy,” Ashok Kaul, professor of Sociology at Banaras Hindu University, told Gaon Connection over the phone. “That is why about 70-75 per cent of the people remained poor. In the country, 40 crore labourers come from villages. I believe about 40-50 lakh labourers would have returned to their villages due to the lockdown,” he said. “There are about 80 per cent people in the country who are daily wagers and do not have savings, so, it is their compulsion to borrow,” he added.

Rajni, who used to work as a domestic help, borrowed Rs 5,000 from the house she was working at before the lockdown. However, she could not repay the amount as the lockdown extended, and she was not called back to work. “In the month of April, I had taken loan of Rs 20,000 from a moneylender at a monthly interest of 10 per cent. I could barely manage the interest for May, June and July. I had thought that all would be normal in a couple of months but it is going out of control,” rued Rajni, who is from Panchkula district of Haryana.

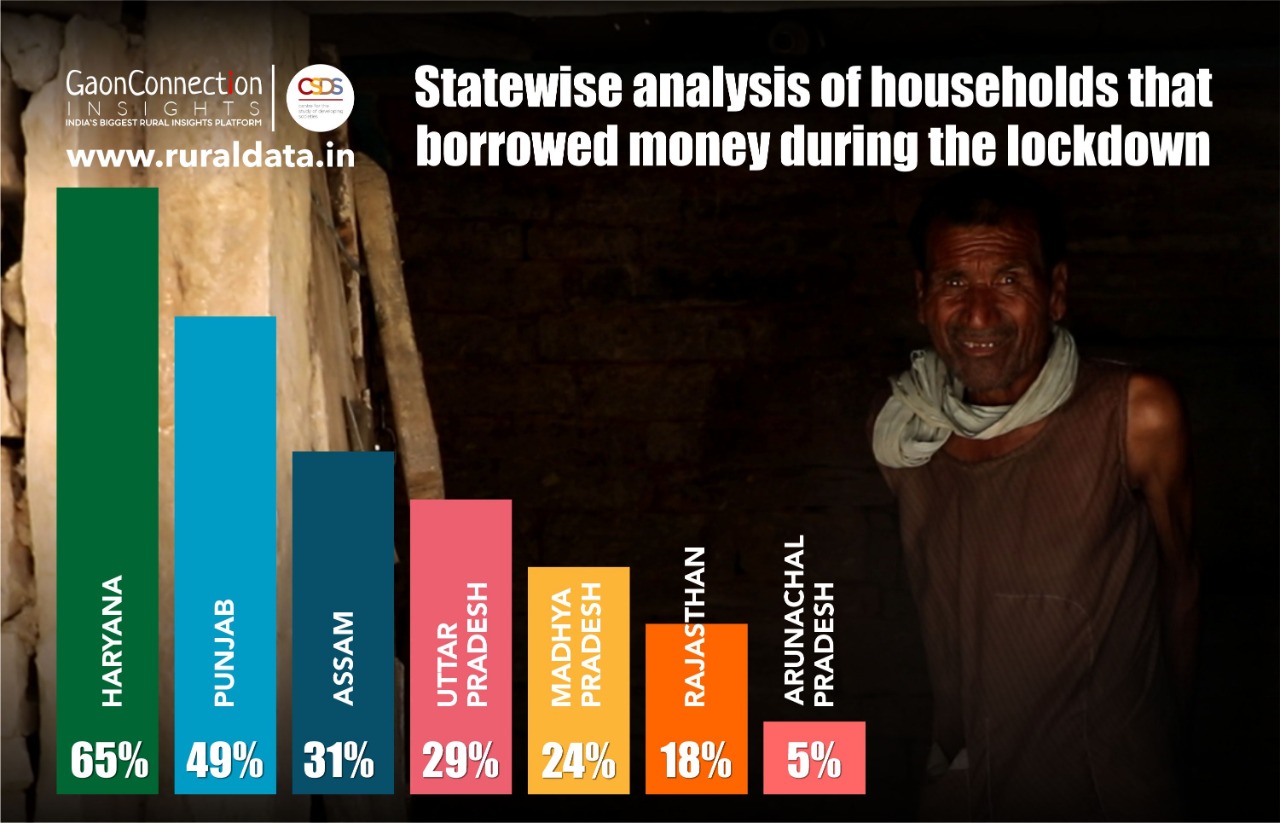

Asha Devi, 37, another resident of Panchkula, had to borrow Rs 5,000 in April as well as May to meet domestic expenses. According to the Gaon Connection Survey, the state with the highest percentage of borrowing is Haryana, with 65 per cent households claiming they took loan during the lockdown.

Looking at the statewise survey, it can be observed that in Haryana, Punjab, Assam, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh people have borrowed more loans than in other states. In Tripura, 13 per cent had to sell off or mortgage land and 20 per cent their valuables. In West Bengal, 22 per cent of people had jewellery and 17 per cent had their valuables sold or mortgaged.

“All orders for making idols were cancelled in lockdown. But the workers who had been working with us for many years cannot be removed from the job. So, I took a loan of six lakh rupees and paid the employees,” said Pradeep Pal, who owns a factory in Cooch Behar district, situated 700 kilometres away Kolkata in West Bengal and has the oldest and perhaps the largest community of kumhar (potters or clay craftsmen).

Why are people compelled to sell or mortgage their jewellery, land and valuables? As per the report released by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in Geneva, 19.5 crore people worldwide could lose their livelihood this year. The ILO has described COVID-19 pandemic as the worst crisis since World War II.

Arun Kumar, a retired economist from Jawaharlal Nehru University, provided the rationale behind borrowing. “The benefit of the policies framed by the government do not reach the villages. The entire business cycle has been paralysed due to non-increase in demand for products of various companies. Employment has nosedived and nearly everybody is sitting unemployed. One will then have to take a loan to feed oneself,” he said.

“The government has provided an additional Rs 40,000 crores to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme which I believe is quite inadequate because the number of migrants reaching the village is substantial. According to me, its budget should have three to four lakh crore rupees so that more and more people can get employment rid themselves of the need to borrow,” Arun Kumar pointed out.

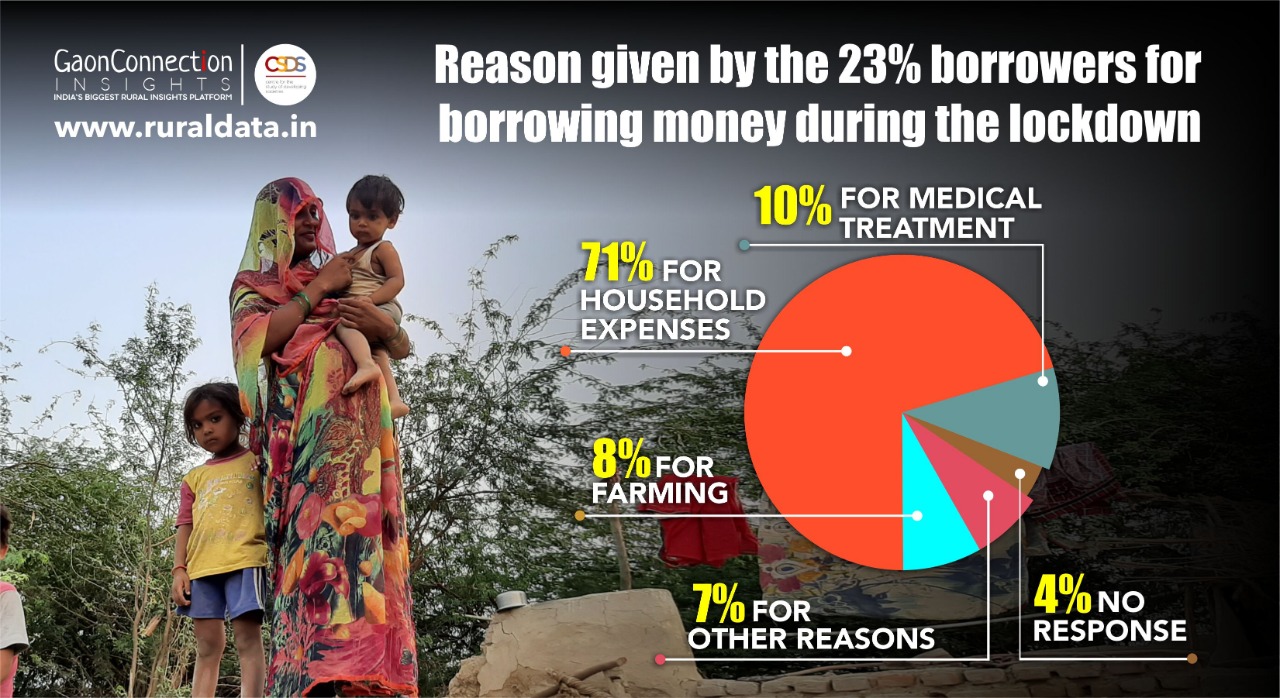

Among the 23 per cent people that had borrowed money, 71 per cent did it to meet domestic expenses, while 10 per cent cited medicines, hospital expenses and 8 per cent agricultural work and 11 per cent reported other reasons for borrowing. Four per cent of the people did not respond.

Mewalal of Lucknow’s Atesuva village had to pledge his wife’s jewellery to provide food for his family. “I had to pledge my wife’s jewellery as I could never earn enough to save for times like these. Currently, we are spending the sum for procuring food. I hope to free the jewellery later by working hard,” Mewalal, 65, told Gaon Connection, saddled with guilt and helplessness.

In Uttar Pradesh, 29 per cent of people had borrowed money or had taken loans. Seven per cent mortgaged or sold the land, eight per cent had to sell some of their valuables, while eight per cent had to sell or pawn jewellery.

During the lockdown, the government sent money directly to the accounts of the poor under different items such as Jan Dhan, Ujjwala, old age pension, PM Kisan Fund but as per the survey data, 69 per cent of the people faced great difficulties as the government aid received was not adequate for them.

Two-thirds of the families surveyed said that they had faced a shortage of food items in lockdown. 32 per cent found it overly difficult to access food in lockdown while 36 per cent found it difficult and 22 per cent had marginal or occasional difficulty in finding food.

In Jammu and Kashmir and Laddakh, 56 per cent people had faced acute food problem, while 47 per cent in Uttarakhand, 43 per cent in Bihar, 41 per cent in West Bengal, 40 per cent in Haryana and 39 per cent in Jharkhand admitted to facing food problems. In Kerala, only 9 per cent of the people found it difficult to eat. The survey clearly revealed that the poor were the highest among those suffering during the lockdown.