Only half the farmers aware of the Centre’s new contract farming law: Gaon Connection Survey

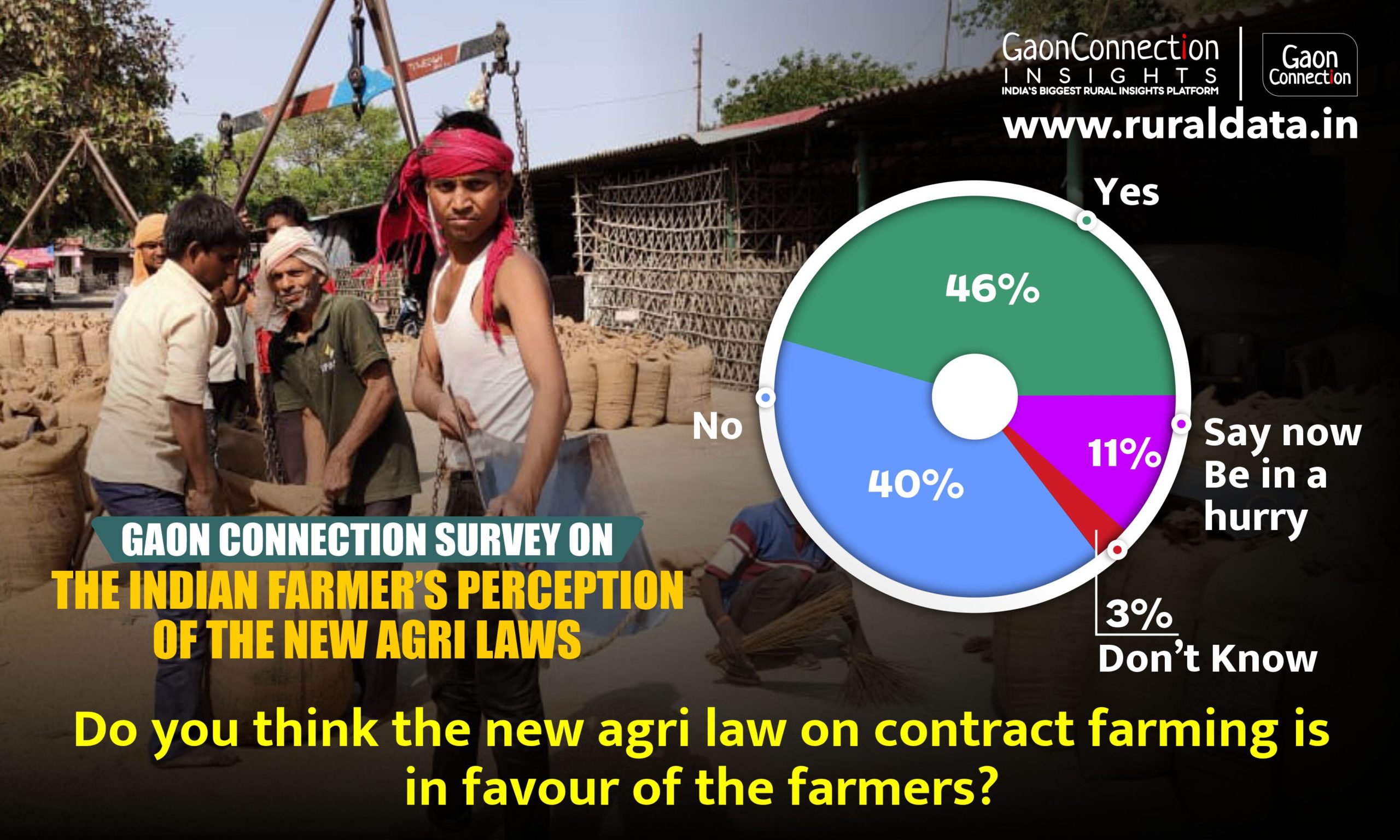

Of the 49 per cent farmers who are aware of the new contract farming law, over 46 per cent said the law was in favour of the farmers, while 40 per cent did not think so.

Photo: Pixabay

Even before the enactment of the new agri laws, many small farmers in states such as Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Haryana have been undertaking contract farming. And quite a few have had bitter experiences. “In 2018, 65 farmers like me cultivated aloe vera under contract, but when the yields suffered due to rain, the company disappeared from the scene instead of claiming the produce,” recalled Kailash, a farmer from Belhara village in Barabanki district of Uttar Pradesh.

“Only after much effort could the company be persuaded to buy a little produce from the farmers, and that too at a price lesser than agreed. We farmers gave up the contract,” he said. Six years ago, the same set of farmers suffered a loss in the contract farming of turmeric.

One of the prickly issues in the three agricultural laws recently introduced by the central government and passed by Parliament has to do with contract farming.The Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, gives farmers the right to enter into a contract with agribusiness firms, processors, wholesalers, exporters or large retailers for the sale of future farming produce at a pre-agreed price.

Gaon Connection recently conducted a rapid survey, ‘The Indian Farmer’s Perception of the New Agri Laws’, among 5,022 farmers in 53 districts across 16 states to document how farmers in the country perceive the three new agri laws. The findings show that only half the respondent farmers, 49 per cent, were aware of the new contract farming law. This awareness was highest among farmers in the west zone (Gujarat, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh) at 75.4 per cent, followed by the northwest zone (Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh) at 55.8 per cent. The least awareness was in the east-and-northeast zone (Assam, Odisha, West Bengal and Chhattisgarh) where 37 per cent farmers said they were unaware of the contract farming law.

Source: https://insights.gaonconnection.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/The-Rural-Report-2.pdf

Another important finding of the recent Gaon Connection survey is that of those farmers who said they were aware of the contract farming law, a larger percentage of marginal and small farmers (51 per cent), who own up to two hectares land, think that contract farming law was pro-farmer than medium and large farmers (37 per cent).

Source: https://insights.gaonconnection.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/The-Rural-Report-2.pdf

In contract farming, under a written agreement between a company and farmer, the company provides everything from seeds, fertilisers and technology to the farmer, who raises crops for the company. The produce is sold to the company at a predetermined price, and the money goes directly to the farmer. According to the Central government, the new law will guarantee farmers a sale even before sowing.

But, a number of farmers and farmers’ organisations in the country look upon the contract farming law as a death warrant for farmers.

For instance, Jaimin Patel, an organic farmer of Kavitha village in Bharuch district of Gujarat, has been raising a variety of fruit and vegetable crops for the last seven years. “Our state already has contract farming, and farmers have shouldered losses in case of poor quality of crop,” he told Gaon Connection. “Contract farming may be a good option, but it is important that farmers learn about the quality and grading of the crop before entering into an agreement with a company. Lack of information will result in suffering,” he warned.

Meanwhile, in Bastar division of tribal-dominated Chhattisgarh, Raja Ram Tripathi is part of a group of about 700 farmers who cultivate wild medicinal plants over several hectares of land. He does not support the new law on contract farming. “There are many discrepancies in this law. The government may make tall claims about contract farming. However, the big companies don’t come in to save farming, but to make a profit,” he said.

Farmers’ organisations across the country have demonstrated against the latest agricultural laws. They allege these laws will decimate small and marginal farmers by allowing big private companies into the agriculture sector.

“Every coin has two sides. Nothing is really bad in this, but small farmers fear that some corporate executive will enter and appropriate their stake,” said Kedar Sirohi, acting president of the Kisan Congress in Madhya Pradesh.

There is also the issue of exclusivity. “If a farmer’s small crop in contract farming is of low quality, he has no means of knowing how much lesser than the agreed price he will get,” he informed. “As in the case of PepsiCo, if farmers sell their produce elsewhere, there will be legal implications, adding to their hardship. Companies will take advantage in the name of quality, and the farmer will not receive payment, as there is no monitoring,” he cautioned.

Farmers’ organisations also fear that with the entry of corporates, farmers will turn labourers in their own fields. However, the government denies these arguments.

Union agriculture and farmers welfare minister Narendra Singh Tomar said that under the act, only the crop would be part of the contract, not the field, and that farmers would be free to give up the contract whenever they wanted.

Pointing out that there had been no such law so far, because of which corporates were reluctant to work in villages, the minister assured that the new law would increase investment in rural areas, and farmers would get more opportunities to cultivate cash crops other than wheat and paddy.

Companies associated with agricultural industries also believe that the new law would benefit farmers who are doing good work and harvesting quality produce. “Farmers associated with our company are getting 20 per cent to 30 per cent more income because they directly access the buyer, without any mandi,” said Shyam Sundar Singh, owner of Dehat, which works with 330,000 farmers across Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Odisha. It provides seeds, fertilisers and technology to farmers and has a produce procurement facility too, on the lines of contract farming.

“A reform is not an endgame in itself, rather a beginning. As an agri-tech company, we welcome it. In the form of agricultural laws, there has been a beginning, and the gaps can be removed in the course of time,” he added.

However, Sanjay Kumar, principal scientist of Lucknow-based Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, who has been working on contract farming with farmers for nearly 15 years, claimed there has not been much work done in India on contract farming. “Although the shortcomings of the law can be weeded out, it won’t succeed till there is trust established between farmers and corporates,” he told Gaon Connection.

“It would have been better to include a local government institution in contract farming, besides the farmer and the corporate, to breed trust on both sides. There is an absolute need for monitoring and control at the local level, because contract farming is getting discredited, not by the big companies but by the middlemen and smaller companies,” he added.

Read the story in Hindi.