The disappearing Puducherry beach comes back to life. An artificial reef came to its rescue

An artificial reef has helped restore a part of the Puducherry beach. But, more interventions are needed to complete this pilot project that can guide beach restoration along India’s coastline

Puducherry

Right opposite the Secretariat building in Puducherry (historically known as Pondicherry), a portion of beach juts out into the sea. Residents, children and tourists enjoy walking on the beach sand and clicking selfies with the sea waves. Young couples walk hand in hand enjoying the cool sea breeze.

But, just over a year ago, there was no beach in Puducherry. A stone seawall and a promenade were unsuccessfully trying to keep waves of the Bay of Bengal from destroying the inland infrastructure. The beach road had developed cracks, threatening to erode into the sea.

That’s when the National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT), a Chennai-based research institute attached with the Union ministry of earth sciences, decided to implement a unique beach restoration project in Puducherry.

“Rather than using concrete structures like groynes and stone seawall, we adopted a sustainable project for beach restoration at Puducherry,” MA Atmanand, director of NIOT told Rural Connection. “After research and modelling studies, an artificial reef was submerged into the sea, which, in the last one year, has helped restore a part of the beach. Both local people and tourists now use it for recreation,” he added.

Beaches are not just spaces for recreation. Beaches are rivers of sand. They support marine life and livelihood of fishers, and also keep a check on groundwater salinity.

The Puducherry beach restoration project has received the support of the local residents and environmental organisations.

“Till the 1980s, Pondicherry used to have a beautiful sandy beach, which slowly started to disappear after the construction of Pondicherry harbour in 1989. Soon, we lost our entire beach with sea waves threatening to eat into the infrastructure,” said Probir Banerjee, president of Pondicherry Citizen’s Action Network (PondyCAN), a Puducherry-based environmental organisation. “We spent decades trying to get the government to address coastal erosion, but to no avail. Finally, the NIOT implemented its project, which has borne fruits,” he added.

A year ago, in January 2019, Harsh Vardhan, the Union minister of earth sciences, inaugurated the restored Puducherry beach lauding the efforts of NIOT.

“The pilot project by NIOT has successfully demonstrated how a beach can be restored,” said M Rajeevan, secretary, Union ministry of earth sciences. “But, we must also remember that beach restoration is costly. The Puducherry project costed about Rs 30 crore. Our first priority should be to avoid coastal erosion and protect our beaches,” he added.

How a beach disappeared

Puducherry, 151-km south of Chennai, always had a beautiful sandy beach. People who grew up in the union territory in the 1960s-70s-80s, remember early morning walks and sports activities on the beach.

Things started to change in 1989, claim local environmentalists.

“That time the Centre was giving funds to various state governments to build harbours and ports. Harbour construction started in Puducherry in 1989,” said Banerjee. “The harbour stopped the movement of sediment, thus depriving our beach of its sand leading to its disappearance,” he lamented.

This is noted in a 2011 report of the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management under the Union ministry of environment, forests and climate change: “… zones of erosion have increased, possibly related to the construction of the Puducherry Port in the late 1980s and other groyne field structures along this part of the coast subsequent to the construction of the Puducherry Port.”

Explaining the science behind it, J Ram Kumar, a project scientist with Chennai-based National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR), another institute under Union ministry of earth sciences, said: “Coast is like a river of sand with continuous movement of sand due to wind and waves. When you construct a structure on the coast, you essentially build a dam to stop the movement of sand. Places where sand cannot reach start to erode.”

Interestingly, on the east coast of India, where Puducherry is located, waves approach the coast from the southwest direction for about eight to nine months a year. This southwest approach of waves induces northward transport of sand. If a coastal structure is constructed, then accretion takes place on the southern side and erosion on the northern side of the structure, explained Kumar.

For the rest three months of the year, which is during the northeast monsoon (October to December), the waves approach from the northeast side and the sand moves in the opposite direction. This movement of sand is known as longshore drift or beach drift.

According to Banerjee, when the harbour was proposed, the Central Water and Power Research Station (CWPRS) was aware of the fact that longshore drift will be affected. Hence, in the design document, dredging of sand — sand bypass system — was a part of the project. As per it, sand had to be regularly dredged from the south of the harbour and pumped to the north to ensure Puducherry beach does not disappear. But, the same was not carried out and our beach completely vanished in the next few years, he complained.

The 2011 report, too, notes: “… the sand bypassing system has not been utilised appropriately. Because of this, deposition occurred on the south side of the breakwater and erosion on the north side of the northern breakwater. For the protection of shoreline erosion, the Puducherry government has built riprap using boulders… In many places along this riprap, the seabed below the riprap is eroded due to severe wave action and ground subsidence.”

This report of the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management concluded that the “shoreline of Puducherry has undergone high erosion on a long-term basis… The coast adjacent to the south breakwater, sediments are trapped on the southern side of the breakwater and, as a result, there is no net sediment movement towards the north of the Puducherry Port, causing erosion on the northern side of the north breakwater

“We have had beach erosion for about 30 years in Puducherry, which corresponds with the construction of the harbour. A huge hole in the coast has been created in the last three decades that now needs to be filled up with sand to restore our beach,” said Aurofilio Schiavina, co-founder of PondyCAN.

Coastal erosion all along the coastline

Puducherry isn’t the only coastal area in the country facing erosion. India has a long coastline of over 7,516-km of which 6,100-km is in the mainland.

A July 2018 joint report, National Assessment of Shoreline Changes along Indian Coast (1990-2016), by NCCR and Union ministry of earth sciences has scientifically documented shoreline changes along a 6,031 km coastline using satellite images. The results are classified in three categories — erosion, stable and accretion.

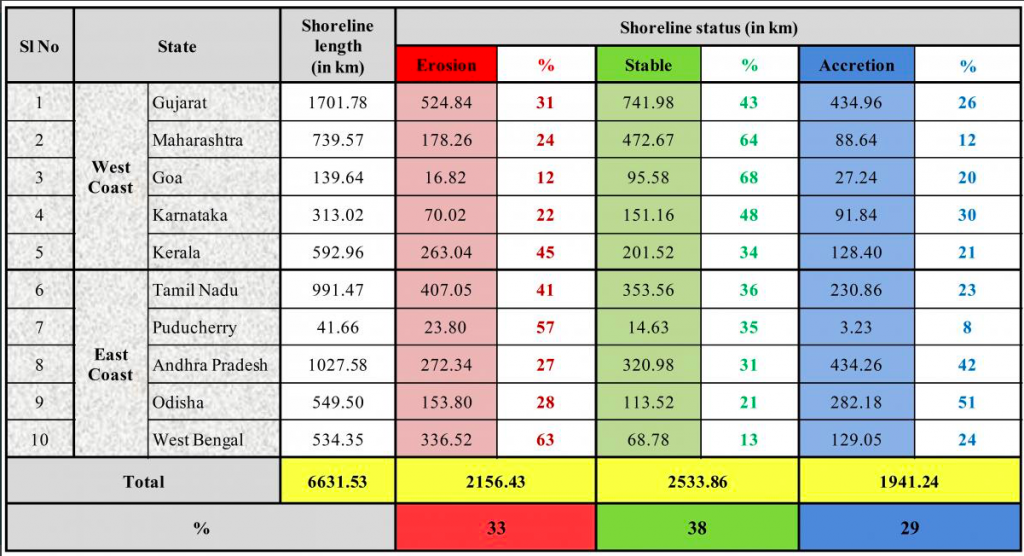

The study found that between 1990 and 2016, about 34 per cent of the Indian coastline is facing coastal erosion, 28 per cent has accretion, whereas 38 per cent is stable (see table: Shorelines changes along the Indian coastline 1990-2016). More than 40 per cent of the total erosion has been recorded in four coastal states of West Bengal, Puducherry, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Table: Shorelines changes along the Indian coastline 1990-2016

Source: National Centre for Coastal Research, Chennai

Coastal erosion is both a natural phenomenon and impacted by human actions. Waves, winds, tides, nearshore currents and storms cause natural changes to the coast. Anthropogenic activities, such as the construction of harbours and jetties, dams, seawalls, beach sand mining, destruction of mangroves, etc exacerbate coastal erosion.

Puducherry beach restoration project

As per the July 2018 report, 57 per cent of Puducherry’s coastline, the second-highest in the country, is facing erosion. To address coastal erosion, NIOT has implemented a pilot project in the union territory.

In the original project document, Detailed Design Report on Pondicherry Beach Restoration Project, there are three components of the beach restoration project: a nearshore wedge reef, south reef, and beach nourishment using 450,000 cubic metre of sand (see figure: Components of Puducherry beach restoration project).

So far, only one component — wedge reef — has been completed.

Figure: Components of Puducherry beach restoration project

Source: Detailed Design Report on Pondicherry Beach Restoration Project, NIOT, Chennai, May 2016.

The wedge reef is a triangular shape steel caisson resting on a bed of rocks laid horizontally at 2.5 m depth. It is 50 metres (m) in width and 60 m in length. The reef crest is designed to be at the water surface at low tide and submerged by more than one metre during high tide.

The wedge reef component of the Puducherry project was started in May 2017 and ended in October 2018. In the last 15 months, positive results are showing up. A sandy beach has come up right opposite the Secretariat building where reef has been submerged in the sea.

“The reef tries to modify the wave environment locally through wave transformation. It tries to change the wave direction, thereby changing the direction of the sediment or sand transport,” explained Kumar. “The reef stops the sediment from moving north. But, during high tide, when it is submerged one metre below sea level, sand can move northward, which is desirable so that the north doesn’t become sand deficient,” he added.

Explaining the benefits of wedge reef, Schiavina said: “The advantage of reef compared to other structures designed to retain sand is that the reef retains only as much sand as is needed to restore the eroded beach. It does not deprive other beaches of their fair share of sand. It behaves like a speed breaker.”

Project isn’t complete yet

A wedge reef is just one component of the beach restoration project at Puducherry. The entire coastal protection project at Puducherry involves three components — wedge reef, south reef, and beach nourishment component.

The wedge reef component had to be implemented by the NIOT, which has been done. The rest two components are to be implemented by the state government, but delayed due to a lack of funds. All the three components combined are expected to protect the coastal stretch of about 1.5-2 kilometres.

As per the news report, Lieutenant Governor Kiran Bedi has asked the Union ministry of earth sciences to “allocate adequate funds for extension of the beach on the southern side.” But, the ministry’s role was limited to the wedge reef component of the project and the other components had to be implemented by the Puducherry government.

Meanwhile, the NIOT has implemented another coastal protection project at Cuddalore Periyakuppam village located between Mahabalipuram and Puducherry.

“In this fishing village, fishers had lost their beach where they used to mend fishing nets, bring fish catch and auction it. We have installed a geo-tube based shore protection method, which has helped restore the lost beach,” said Atmanand.

Explaining the functioning of geo-tube bags, Kumar said that geo-tube is a bag made of naturally available materials, filled with sand and placed in the sea, away from the shoreline, at Cuddalore Periyakuppam site. The function of geo-bags is to reduce the wave energy coming to the coast by making the waves break off-shore.

“At Cuddalore Periyakuppam, there are three geo-bags — two at the bottom and one at the top installed in the sea slightly away from the coast. These geo-bags cover a length of 1.5 kms and have helped protect the beach from coastal erosion,” informed Kumar.

However, the local fishers haven’t warmed up to the idea of geo-tube bags and told Rural Connection they wanted a seawall or groynes. Several groups have also questioned the efficacy of geo-tube bags to protect the beach. They claim geo-tubes have failed to protect shoreline in several other states.

A wedge reef, however, has been a welcome intervention.

“Constructing a seawall or putting groynes is a reaction to an immediate crisis. It only shifts the problem elsewhere,” said Banerjee. “Wedge reef is essential and has shown a beach can be protected and restored,” he added.