Subsidy worth crores, monetary fines and seeder technology too; but no end to stubble burning in Punjab

Sangrur district of Punjab is one of the hot-spots for stubble burning that recorded 566 fire cases on November 11. Gaon Connection visited Sangrur to find out why despite doling out millions of rupees as subsidies and offering crop residue management machines, farmers continue to set their fields on fire. Cultivators said they were forced to burn the crop residue. Is there a win-win solution?

Sangrur and Patiala, Punjab

“Wait for 3 pm, the entire sky will turn dark grey as farmers start burning their crop stubble. These days every evening, visibility becomes low, one’s eyes sting constantly and it becomes difficult to breathe,” Raghvir Singh, a farmer based in Sangrur district of Punjab, told Gaon Connection. He was standing in an open field where paddy had just been harvested and its dry residue waited to be set on fire to prepare the land for the next crop of wheat.

Over 230 kilometers north-west from Delhi, one would expect the fields to be a little more greener and the skies to be clearer and bluer than the heavily polluted air of the national capital, which is enveloped in smog for the past one week now.

However, far from witnessing either of those in Sangrur – one of the districts worst affected by stubble burning in Punjab – it takes only a couple of minutes to get covered in a layer of black soot. As the farmers prepare their farms for the next crop and burn parali, a local term for the paddy residue, a thick layer of grey descends and even a double face mask cannot filter out the burning smell in the air.

Also Read : Stubble Trouble: Air quality dips in Delhi; spotlight shifts to farmers in Punjab and Haryana

“Parali humari jee ka janjaal bani padi hai. I don’t like burning stubble either but what other option do I have?” questioned Satvinder Singh, a small farmer who owns five acres (about two hectares) of land in Sangrur.

“The super-seeder and happy seeder machines cost two-and-a-lakh rupees. Even if I take it on rent, I don’t have a 55 hp (horsepower) tractor to run it. I only have a 35 hp one, which can’t be used to run these machines to tackle parali,” the farmer added.

Winter is here and so is the annual season of smog and sickness in Delhi and the Indo-Gangetic Plains region of India. It is also the time when the blame game will be at its peak. The Delhi government will blame farmers in Punjab and Haryana for causing air pollution by burning the crop residue in their fields. Farmers will complain that no government has offered them a viable solution to the problem.

Also Read : Delhi’s worst Diwali night in the past 5 years, first smog episode to last for seven days: CSE

Meanwhile, the central government will ask ‘tough’ questions to the commission for air quality management it had set up last August to tackle air pollution in NCR and adjoining areas. And it will be business-as-usual till next winter.

A fiery issue

Till two days back, on November 10, Punjab had recorded a total of 55,573 cases of farm fires so far this year. Of these, 4,156 fire counts were recorded on that day itself and Sangrur’s contribution was the highest – 566 (about 14 per cent). This data was provided by the Punjab Remote Sensing Centre, Ludhiana.

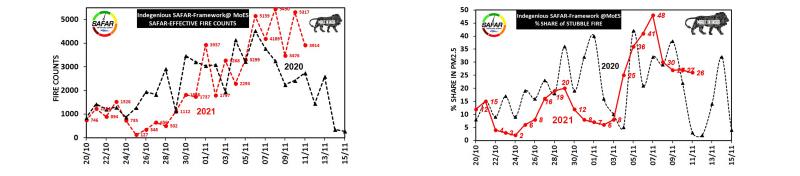

According to SAFAR (System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting and Research) developed by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) Pune, on November 7, the contribution of stubble burning to Delhi air pollution (PM2.5) stood at 48 per cent. This has come down to 26 per cent today on November 12. But, as per the weather forecast of SAFAR, air quality is expected to dip further in the next two days in the national capital due to wind direction and an expected rise in the fire counts.

While the government claims to have taken measures to keep a check on the number of stubble burning cases including subsidising crop residue management (CRM) machines, issuing challans to those farmers who set their fields on fire, and offering other financial incentives.

For instance, this year environmental compensation of Rs 6.5 million has been imposed on 2,364 sites in Punjab, as per data shared by Krunesh Garg, an official at the Patiala branch of the Punjab Pollution Control Board.

The number of fire counts has come down from last year to this – 76, 590 fire counts between September 15 and November 30 in 2020, to 59, 121 fire counts till November 12 this year – stubble burning remains a burning issue. Farmers in Punjab, including a large chunk of small and marginal cultivators, claim they are forced to burn the crop residue and need some ‘real solution’.

Why subsidies are not working

Happy Seeder and Super Seeder machines are tractor mounted machines that cut, lift rice straw, sow wheat into the soil, and deposit the straw over the sown area as mulch. It, therefore, allows farmers to sow wheat immediately after their rice harvest without the need to burn any rice residue for land preparation.

The average maximum price of a Happy Seeder is Rs 151,200. The average maximum permissible subsidy per Happy Seeder per beneficiary is Rs 75,600, which is 50 per cent of the total cost, as per the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare 2018.

The Punjab government provides a 50 per cent subsidy to individual farmers to buy the super-seeder and happy-seeder machine and the farmers cooperatives get a subsidy of 80 per cent.

However, despite the technology and the subsidy, many small and marginal farmers (cultivators who own less than five acres or two hectares of land) in Punjab are unable to access both because they don’t own the tractors, which should have at least 55 hp, to run these machines.

According to the Agricultural Census 2015-16, about 14 per cent of farmers in Punjab are marginal farmers (owning less than one hectare of land), whereas about 19 per cent (owning less than two hectares of land) are small farmers.

“If I depend on these (happy-seeder) machines, I will have to spend three lakh rupees to first buy them and then an additional seven lakh rupees for the 55 hp tractor,” Harjinder Singh, a farmer based in Gharachon village of Sangrur, told Gaon Connection.

Also Read : Can the Centre’s new ordinance on air pollution clean up NCR-Delhi’s air? Experts’ opinion divided.

And this is not all. “There is going to be additional expenditure on the diesel to run the tractor. How can a small farmer who owns five acres of land afford that? The cheapest option is to buy a matchbox and set the stubble on fire,” the desperate farmer added.

“Last year diesel prices were Rs 60-65 a litre and now it has crossed Rs 100 per litre. We require 10-12 litres of diesel on one acre of land while sowing the seeds. We have to spend Rs 1,600-1,700 on diesel,” Satvinder Singh of Gharachon village in Sangrur, explained.

Additionally, the price of DAP fertiliser has also shot up adding to the woes of the farmers, he said. “The packet [about 50 kg] which used to come for Rs 465 is now being sold for Rs 1, 250. The big traders collude with the government and keep DAP stocks with themselves and are now selling it in black market for Rs 1,700,” Satvinder complained.

Also Read: Fertilisers ‘shortage’, exhausting queues throw farmers in turmoil

As per the Directorate of Information and Public Relations, Punjab, last year the state government had decided to provide a subsidy worth Rs 3,000 million to the farmers for the purchase of 23, 500 farm equipment for the management of paddy residue. Additionally, the state government had claimed to have provided over 51,000 such machines to farmers with a subsidy of Rs 4,800 million in the last two years.

Moreover, as per the news reports, the central government released Rs 4,910 million to Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh for tackling the stubble burning issue in 2021-22. Of this, Rs 2,350 million was released to Punjab alone. Apart from this, Rs 8,156 million more has been released to Punjab in the last four years as a part of a central scheme on promotion of agri-mechanisation for the management of crop residue.

However, the problem of stubble burning persists.

The impact of provision of subsidy to the farmers’ cooperatives hasn’t been very effective, Lakhwinder Singh, former professor and head of department of Economics at Patiala-based Punjabi University, told Gaon Connection. “There are very few cooperatives operating effectively in Punjab. On top of that, they don’t have a very wide reach since they don’t have enough machines to meet the demands, hence subsidies to them also aren’t effective,” he said.

Why technology is not working

As per the official data, 76,626 crop residue management (CRM) machines were deployed in Punjab in 2020 which included 13,316 happy seeders and 17, 697 super seeders machines. Sangrur had the maximum number of happy seeders and super seeders.

On the other hand, the sown area under kharif paddy in Punjab in 2021 was 3.066 million hectares that is 2.6 per cent lower than 3.194 million hectare in 2020. Out of this sown area, the state is expected to generate nearly 16 million tonnes of residue.

Analysing the available data, the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) India’s 2021 report – Why Paddy Stubble Continues to be Burnt in Punjab? – states that the enormous quantum of stubble makes its management a logistical issue.

As per the report, Punjab is still short of CRM machines to cater to the large area under paddy and the current penetration is limited to a few high-burn districts in Amritsar, Patiala, and Ludhiana, and is below the ideal requirement. The think-tank also declared that these machines are under-utilised.

Also Read : In the line of fire, thousands of hectares of standing crops

Misconceptions around machines

In addition to the shortage of CRM machines, the farmers’ perceptions of the impact of Happy Seeder on the productivity of wheat sown using this machine is a cause of its low popularity. This machine sows wheat without removing the paddy stubble which results in the field looking yellow and the farmer is gripped with anxiety about the health of the wheat crop, thus posing a major psychological barrier for the farmers, the CEEW India report states.

“The happy seeder doesn’t remove the stubble properly and when we sow our seeds on that land, it gets infected by pests. Last year, my entire crop was destroyed due to this,” Harjinder Singh, a farmer from Gharachon village, told Gaon Connection.

Apart from this, the government is also trying to promote PUSA bio-decomposers which convert stubble into compost. Introduced as capsules that take 20-25 days to decompose the paddy residue, this has few takers among the farmers.

“After harvesting paddy, we only get one week to cultivate wheat. If we take longer than that then it can impact our produce. Moreover, the decomposer sprays take 15-20 days to decompose the residue. We don’t have that much time on our hands,” Raghvir Singh, a farmer based in Gharachon village of Sangrur, complained.

He suggested that the government should pay a cash incentive of Rs 200 per quintal for the paddy residue so that it can be used by the farmers, especially those who have limited income, to hire labourers for removing the paddy residue from their fields.

Also Read : Farmers’ protests: Compensate farmers if you do not want them to burn paddy stubble, demands Rakesh Tikait

Agreeing with this suggestion, Kurinji Selvaraj, a programme associate at CEEW India, stated that while the government could provide financial assistance to farmers who use in-situ crop residue management (incorporating stubble back to soil using machines or through composting techniques), the long-term solution lies in moving away from growing paddy.

“Haryana has been promoting crop diversification for years now through cash incentives. While there are problems with the procurement of crops other than paddy at MSP (minimum support price), the Punjab government should formulate a plan that involves persuasion and incentives to make this happen,” said Selvaraj.

‘Machines alone cannot solve the problem’

There is a pressing need to find alternative uses of the paddy residue outside agriculture instead of using machinery to remove the stubble or decomposing it, explained Lakhwinder Singh, former professor with the Punjabi University. “The government and even several experts are suggesting that this problem will be solved through machines, however, that’s not possible,” he said.

Krunesh Garg, an official at the Patiala branch of the Punjab Pollution Control Board told Gaon Connection that a compressed bio-gas plant was under construction near Sangrur which will pick up 30,000 tonnes of paddy straw this year and convert it into biogas. This will aid in reducing the number of stubble burning cases, he said.

Talking about the need to provide proper infrastructure so that farmers may make some money out of it, Garg said: “This is not a one year or a three-year job. We are trying to ensure that fewer fire counts take place every year and there is a decrease in burnt area also but it will take time.”

In its 2021 study, CEEW India has concluded that the state government’s policy measure to allow industries to use crop residue in their boilers is a step in the correct direction. However, the report also notes that it may only have a little impact and will take time to mature.

Also Read : The National Clean Air Programme may fail to clean up the toxic air

Explaining why ex-situ crop residue management hasn’t been very successful either in preventing stubble burning, Selvaraj said, “The alternative to these machines is ex-situ management or using the residue outside the field. While this ex-situ utilisation can take several forms, such as fodder for cattle or raw material for packaging, its largest (envisioned) use is in the form of fuel in power plants and industries.”

She also added that the ex-situ residue management faces logistical hurdles: “Punjab’s capacity to use paddy residue as fuel for power plants remains below one million tonnes per annum. This is less than six per cent of the residue generated this year.” The ex-situ ecosystem requires a comprehensive policy to bridge the aforementioned gaps, the programme officer added.

Reusing stubble?

The solution, according to the retired professor Lakhwinder Singh, lies in reusing stubble. Crop residue can be used in industries to make papers, cardboard, and ethanol.

Also Read : Nourishing change: In Unnao, UP, an initiative to prevent stubble burning

Pointing towards the flawed policies of the government, he stated that the government never thought of a long term solution to this problem. “The government’s policy-making has been flawed because of which the problem of stubble burning persists. The government has failed to find a long-term solution to the problem,” the former professor added.

While governments, experts and technology solution providers, small and marginal farmers in Punjab continue to set their fields on fire and blame their ill luck.

Kiranjit Kaur, who owns a small piece of land in Gharachon village, blamed the government, and the system for the poor condition of the farmers. “First God betrayed us because of the delayed monsoon which destroyed our crops, then the government and even those whom we go to sell our crops, pay us half the price for our produce. We are living in a hand to mouth situation, we eat what we grow,” said Kiranjit Kaur, who owns a small piece of land in Gharachon village of Sangrur.