By roping in religious leaders and young influencers, Unnao in UP is addressing vaccine hesitancy

The government health authorities in Unnao, UP, are going all out to woo rural communities to come forward to be vaccinated against COVID-19. By roping in religious leaders and young influencers, the district administration is dispelling fears and debunking myths about the vaccine. And this strategy is working.

Women get vaccinated in Peekhi as a result of Naubhar's awareness efforts. Source: Md Dilshad, UNICEF District Mobilisation Officer

At Peekhi village in Unnao district, 22-year-old Naubhar Bano was first in line when the health worker opened the first COVID19 vaccine vial. Although the vaccination for those over 60 years of age and 45-plus with comorbidities started from March 1, not much headway was made in several villages of Unnao due to vaccine hesitancy. In such a scenario of rumours and fears against the new vaccine, Bano volunteered to step up and reassure other members of her village, located 60 kms from the state capital Lucknow, that it was perfectly safe.

Thanks to the young woman, 225 inhabitants of Peekhi in Safipur tehsil, out of the eligible 450, were inoculated.

It was Mohammad Dilshad who had roped in Bano to help him out. Dilshad is the district mobilisation coordinator, appointed by UNICEF, who had to come up with strategies and mobilise ways to encourage people in rural areas to get vaccinated.

People like Bano have been catalysts in the district administration’s Information, Education, Communication (IEC) strategy to spread awareness through communication channels to a target audience to achieve maximum coverage of COVID19 vaccination. UNICEF is a partner in this exercise and so are some other non profits who help mobilise people in rural communities. Mobilisation coordinators like Dilshad identify mosques, temples and other religious institutes, as well as local influencers, who then disseminate information about vaccination camps to the communities.

One of the biggest challenges dealing with the pandemic has been the vaccine hesitancy, especially in rural India. Due to inadequate awareness about COVID19 and lack of proper information, there was rampant fear amongst many rural communities that the COVID19 vaccine could lead to death or impotence among other things.

Rather than being a top-down approach, the IEC strategy focuses on working with the rural communities using means of information dissemination suited best to them. Usually, puppet shows and nukkad natak [street theatre] are a part of campaigns, which have borne fruit in the past. But not this time due to physical distancing protocols the Covid-19 pandemic dictated.

“Bachpan me dadi-nani se suni kahaniyan hamesha yaad rehti hain [one never forgets grandmothers’ stories from childhood],” Lal Bahadur Yadav, who trains 10 block level health education officers in Unnao, told Gaon Connection. According to him, activities such as kathputli tamasha (puppet shows), especially in the local language, immediately struck a chord with people which no amount of pamphlets could do.

“The pamphlets usually end up in the bin. Communication through interactive means stays with the rural population, they process it with ease,” said the health education officer. “Community inclusive performances are impactful, overcome language barriers and establish a two-way communication,” Lal Bahadur Yadav pointed out.

Roping in religious leaders and influencers

According to Dilshad, nearly 1,400 religious leaders from various kasbas in Unnao were involved and this boosted vaccination by 15-20 per cent. In Unwa, Safipur, it was the clergy’s call that motivated the dominant Muslim population to get vaccinated.

A Nigrani Samiti – made up of the district magistrate, gram pradhans, ASHA bahus, anganwadi workers, local teachers and kotedars – hold meetings to track vaccinations in these villages.

A medical officer at Sikandarpur, Unnao, Vijay Kumar Rajoura, recalled how seven years ago at Takiya Patan village in the district, administering the polio vaccine amongst the people of the Nat community, proved to be a huge challenge. It was only when Rajoura persuaded a butcher who regularly dealt with the community to ‘influence’ his customers, that the polio vaccine drive took off.

“This [vaccine hesitancy] is not a new phenomenon. I have seen this reluctance following the introduction of any new immunisation drive,” Vikas Yadav, the medical officer in a primary health centre (PHC) at Sikandarpur, in Unnao, told Gaon Connection, as he dabbed his sweaty face with a handkerchief. It was hot as there was no power, but the medical officer was not complaining as the COVID 19 vaccine drive was going smoothly. Already, 1,200 people had been administered the vaccine that day.

“The pace has picked up ever since the slots for the eighteen-year-olds and above slot has opened up,” Vikas Yadav told Gaon Connection. But he acknowledged that the hesitancy persisted.

“What works is identifying a local figure who the community trusts and listens to and then rope them in to spread awareness. It could be the kotedar, gram pradhan, or even a maulvi or a pandit,” the medical officer explained.

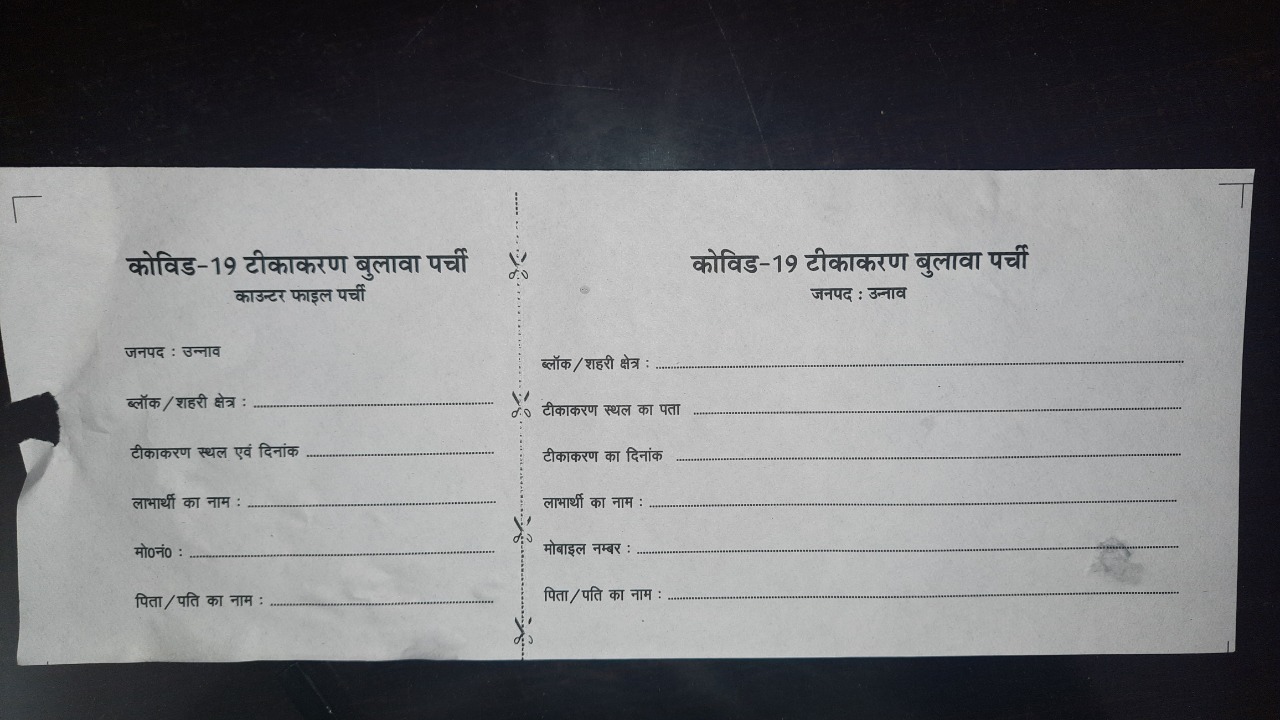

Bulawa Parchis

According to Upendra Singh Chauhan, health education officer, at the Sikandarpur PHC, new strategies are being evolved as they go along. He explained an experiment that was yet to be launched, to encourage more people to come forward and be vaccinated.

“A Bulawa Parchi or an invitation slip will be issued to people requesting them to show up for vaccination,” Chauhan told Gaon Connection. This door-to-door campaign could work in villages, he said. The parchi, with the date and site of the vaccination camp, would be handed over to the head of each family.

“Many people are not aware of the location and date of camps– the parchi fills this information gap and targets the head of the family who is the decision-maker in the household,” he added. “But, it is important to inform villagers about the common side effects. If you do that, they will be prepared to deal with it instead of panicking and resisting the vaccination even more,” Chauhan cautioned.

Kiran Kushwaha, ASHA worker at Korari Kalan village has filled up the Bulawa Parchis, but is waiting for a go-ahead from the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM) as there are not enough doses. She felt that she might not even have to distribute them, as her target population was already eager to get vaccinated.

Fear of missing out on govt scheme

In Sikandarpur, 50-year-old Geeta Gupta was persuaded to get vaccinated in June, after two full months of hesitating. According to her it was her fellow villagers who had been inoculated against the coronavirus, who had persuaded her to do the same. In a ripple effect, her family members followed too. “Sab ek doosre ko dekh kar lagwa lenge dheere-dheere [people will be encouraged by each other and eventually get vaccinated],” Neelam Gupta, an ASHA bahu, from Sikandarpur, told Gaon Connection.

Many villagers are coming forth as they fear government schemes and services will not be available to them if they do not get the COVID-19 vaccine shot.

Also Read: COVID19 in rural India: Shortage of PHC doctors, preference for quacks and high vaccine hesitancy

Md Kareem, a 24-year-old from Korari Kalan took the jab, only so that he could resume his silayi (tailor) job in Mumbai. In Sikandarpur, 66-year-old retired mistry (technician) from the Public Works Department Mohammed Ehsaan took his jab because he heard his pension may be withheld if he did not. Similarly, his neighbour Abdul Lateef had heard that the kotedar would deny them the monthly galla (rations) under the PDS (Public Distribution System) if he did not get vaccinated.

However, there is no truth in these rumours circulating in the villages, say district officials.

Lessons from the past

In February 2018, Uttar Pradesh government launched a massive door to door campaign called DASTAK, to raise awareness on Acute Encephalitis Syndrome(AES) and Japanese Encephalitis(JE). The war cry was “Darwaja Khatkhatao, AES aur JE ko Bhagao” [Knock the door and drive out AES and JE]. This campaign was also based on the IEC strategy.

DASTAK was hugely effective. According to a government report, the AES mortality rate dropped from 24.76 per cent in 2005 to 8 per cent in 2021.

Outside the Sikandarpur PHC, the slogans to fight lymphatic filariasis in red geru on the whitewashed walls still remain – “ASHA didi ki mane baat, Dawa se hi Falaria ko maat” [listen to ASHA didi and defeat filaria with medicines].

In Korari Kalan, ASHA bahu Kushwaha was responsible for writing slogans to increase awareness on filaria and Japanese encephalitis. She pointed out some of the slogans she had written on the walls in the alleys of the village. On a temple wall she had written – Unnao ne thana hai, Falaria bhagana hai, [Unnao has decided to chase out Filaria]; on another she had painted – Chooha aur Chachoondar, jane na do ghar ke andar [keep modes and rats out of your homes].

Kushwaha was convinced that slogan writing enhanced jagrookta or awareness in the people. “The change in attitude [towards filariasis and encephalitis] has happened through government awareness efforts,” she added.

Also Read: Addressing vaccine hesitancy in rural India, one jab at a time

Vaccination Positivity Challenges

The other challenge faced by health workers in rural Uttar Pradesh is vaccine insufficiency. “The Unnao district hospital is capable of inoculating up to thirty thousand people a day. But there are only enough vaccines to cover five thousand people,” Narendra Singh, district immunisation officer, told GaonConnection. He feared that this might impact the momentum of people turning up for vaccines.

According to the district immunisation officer, in May, almost 8,000 jabs a day were administered. But the numbers fell due to unavailability of vaccines. Currently, thousands of people who are showing up to be vaccinated are being turned away every day. This may have an adverse impact on the willingness of people to be inoculated, Singh said.

Aishwarya Tripathi is an independent journalist based in Unnao, Uttar Pradesh. This story was reported under the National Foundation for India fellowship for Independent Journalists.