Warli on the wall: The Warli tribe in Maharashtra’s Ganjad draws from life to create unique art

In Ganjad village in Palghar district, a group of Warli artists keeps the craft alive with residencies and live art shows. The tribe also struggles to stop the unethical commercialisation of its art.

Palghar, Maharashtra

Warli artist Anil Vangad’s dog Preni barks, breaking the deafening silence of Ganjad village in Maharashtra’s Palghar district, about 120 kilometres north of Mumbai. Situated on the foothills of the lush Sahyadris, Ganjad is slowly coming to be recognised as an art village; an important cultural centre where one of India’s most popular indigenous art thrives. The village with 12 padas (hamlets) is home to the Warli tribe of northern Maharashtra and Warli art, popular the world over.

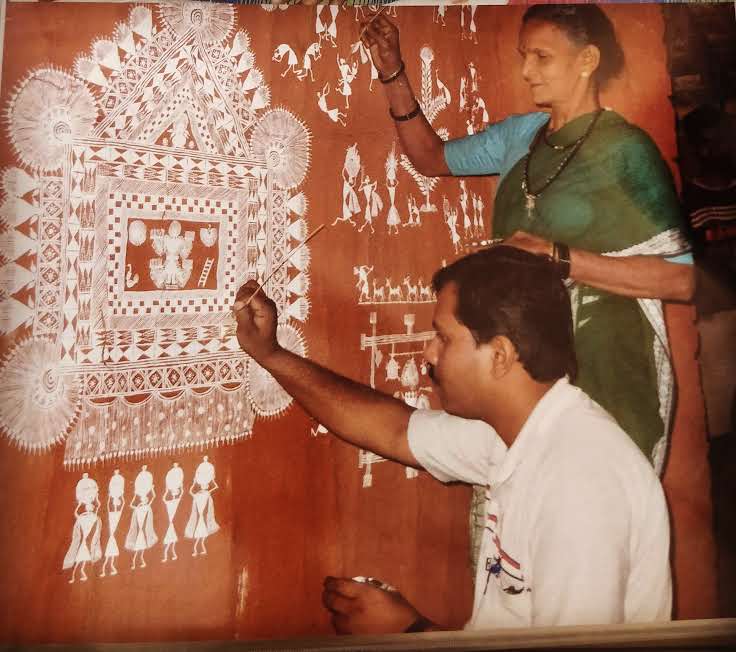

Credit for popularising this art form goes largely to the late Jivya Soma Mashe, the Warli artist who was conferred with the Padma Shri. Anil, 37 years old, has taken that forward. The artist still has fond memories of his grandmother, the late Lakhami Kharpade, narrating stories as she painted them on the wall of her home, dipping a bamboo stick in a watery mix of fermented rice paste and water.

As the story progressed, the wall would grow more beautiful with meticulously-drawn figurines. These were the stories of their ancestors, of gods and goddesses, and of the formidable nature that they lived amidst in Ganjad. Anil now re-creates those stories on canvas, using the skills he absorbed from his grandmother.

Warli comes from ‘Warla’ meaning ‘tilled land’. Warli is the name of the agrarian tribe that tills. “Drawing Warli art, usually on the outside walls of houses, is an age-old tradition among Warli tribals, and its origins date back to the 10th Century, when the art was used as a means of narrating folk tales,” Anil, who has earlier done live paintings and a visual performance art in the US and Europe. told Gaon Connection.

This art of telling stories is an integral part of Warli culture, and is interwoven with the tribe’s everyday life. “As we get on with our work in the farms, we are constantly thinking of creative ways to represent farming through art on our walls,” 27-year-old Shailesh Vangad, a resident of Ganjad’s Vangad pada, told Gaon Connection.

That is among the first things you notice in Ganjad. The walls of each house, coloured brown, earth-red or brown with dung, provides an artistic perspective of various village activities. “The paintings are vivid with elements of nature that the Warlis worship. We also create intricate representations of our Adivasi culture, including our ‘tarpa dance’, which is performed to celebrate the harvest. Without the painting, the performance feels incomplete,” added Shailesh.

The local culture is in the spotlight whenever a new canvas is created on walls — the scenes also depict festivals such as Diwali and Dussehra. “Warli art persuades us to look at our house from a different perspective, to see walls not as barriers but as a medium to express and communicate,” artist and journalist Sanjay Deodhar wrote in his book Warli Art World.

Anil speaks eloquently about this art form, but the wall of his house is blank. This is because the UNESCO WCC [The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and World Craft Council] awardee has been busy completing orders. The walls and shelves of his living room are full of certificates and trophies. “My heart beats for Ganjad, for this is a place where art thrives in all its originality,” he said.

Art as nostalgia

The 40-odd houses in Ganjad’s Vangad pada embody the timeless character of the village through Warli art. However, the paintings evoke nostalgia of a simpler past. They hardly showcase the current intersectional issues in rural India or those faced by tribal communities as a consequence of non-inclusive policy-making and hindered connectivity. This, despite the fact that Ganjad is no exception to this reality. The Warli community, which usually farms rice, continues facing agrarian issues as its fields are rain-fed. “During low rainfall and drought, we face major losses,” Anil explained.

Anil believes that besides its historic value, Warli art can be a powerful tool to initiate social change too. And so, he has started using Warli art to disseminate important social messages.

One of these showcases factory operations painted upon a dead leaf, the result of massive industrialisation and urbanisation. “Nobody cares when a leaf dies. We are so absorbed by industrialisation and technology. What kind of development is this?” Anil questioned.

On the walls of Anil’s neighbour Govind Vangde’s home, the painting seems to depict some kind of celebration. “This is a lagan chitre (wedding scene),” Anil said, as his fingers traced a circle around two seated figures on the painting — the bride and groom. His finger then moved towards a big square — the chowk, a distinctive motif in Warli art drawn by young married women to welcome home a new bride or a new baby, he explained. “The tradition of using Warli art in weddings is perhaps as important as the institution of marriage,” Govind Vangde added.

Promoting art tourism

Everyone in Ganjad is a Warli artist, but only a few have turned their tradition into a full-fledged profession. But this trend is changing. Over the last few years, Ganjad has seen the rise of art-tourists — owing to the popularity of Jivya Soma Mashe, who has travelled countries with his craft.

Mashe’s son Sadashiv, who stays in Ganjad’s Kalambi hamlet stated, “We host several art-residencies in the village. Art enthusiasts stay with us to learn the basics of Warli art and life here, and also commission/buy our products. This has encouraged several people in the village, especially youngsters, to immerse themselves into this art again. The village now has 40 professional artists,” said Sadashiv.

One of them is 40-year-old Gopal Vangad, who told Gaon Connection that art-tourism in the village has boosted incomes. Both Anil and Gopal say Mashe is not just an inspiration, but as someone who paved the way for artists like them.

Unsurprisingly, the professional artists are mostly men. Warli art in the villages have been nurtured and developed by women, specifically the Dhavaleri; the female priestesses of the Warli community who solemnise marriages.

“We have many talented female artists in the community but the village folk are still hesitant to send the girls far-off from home. It’s unfortunate, and while it is no compensation, the successful male artists in our community have always credited the Dhavaleri,” added Sangeeta, Anil’s wife.

Another challenge facing Ganjad’s Warli community is the unethical commercialisation of the art form for use on consumer goods. It has diminished the value of the meticulous processes and ethos that lies behind the Warli art, they say. “Many a time, I come across Warli designs on t-shirts, bedsheets and mugs, all reproduced without permission,” said Anil.

Other villagers echo this sentiment. “The commercialisation of Warli has taken away our agency to tell our stories,” Shailesh said.

The unethical use of Warli art on consumer goods has also led to a distortion of facts around Warli culture. Sadashiv Mashe recounts an example: “Any similar-looking dance is drawn and claimed to be Tarpa dance, the performance and representation of which is very nuanced.”

The art residencies have been one way to curb these practices. Several art enthusiasts have started visiting Ganjad and have greatly benefited from understanding Warli art in all its authenticity.

“I saw Jivya Mashe’s work in a gallery and went to meet him in Ganjad. I understood Warli wasn’t just art in a gallery, but an entire culture. Magic happens here,” stated Anju Kataria, founder of Khazana Gallery in Minneapolis.

To preserve this cultural legacy, there has been talk about opening a Warli Art Center and Museum in the village. In 1976, the Indira Gandhi-led central government had given a one-acre plot of land in Ganjad in the name of Jivya Soma Mashe. “However, 44 years later, the plans still remain stalled due to local politics,” Sadashiv stated.

The artists of Ganjad have been trying to speed up the process over the last 10 years. Anil is hopeful. “Ganjad deserves a Warli Museum so that Warli art is enjoyed in a setting that it truly represents — a village, its people and their lives,” he added.