The coronavirus diseases (COVID19) pandemic has put extreme pressure on the healthcare system in the country, as health professionals and health workers struggle to respond to the health crisis that has gripped the entire world. In order to deal with the rising COVID19 cases, a large number of hospitals and healthcare units in the country have been turned into COVID19 centres.

In this health and humanitarian crisis, how is the healthcare system in rural India, which is already fractured, coping? What happened to the millions of pregnant women in rural India during the lockdown?

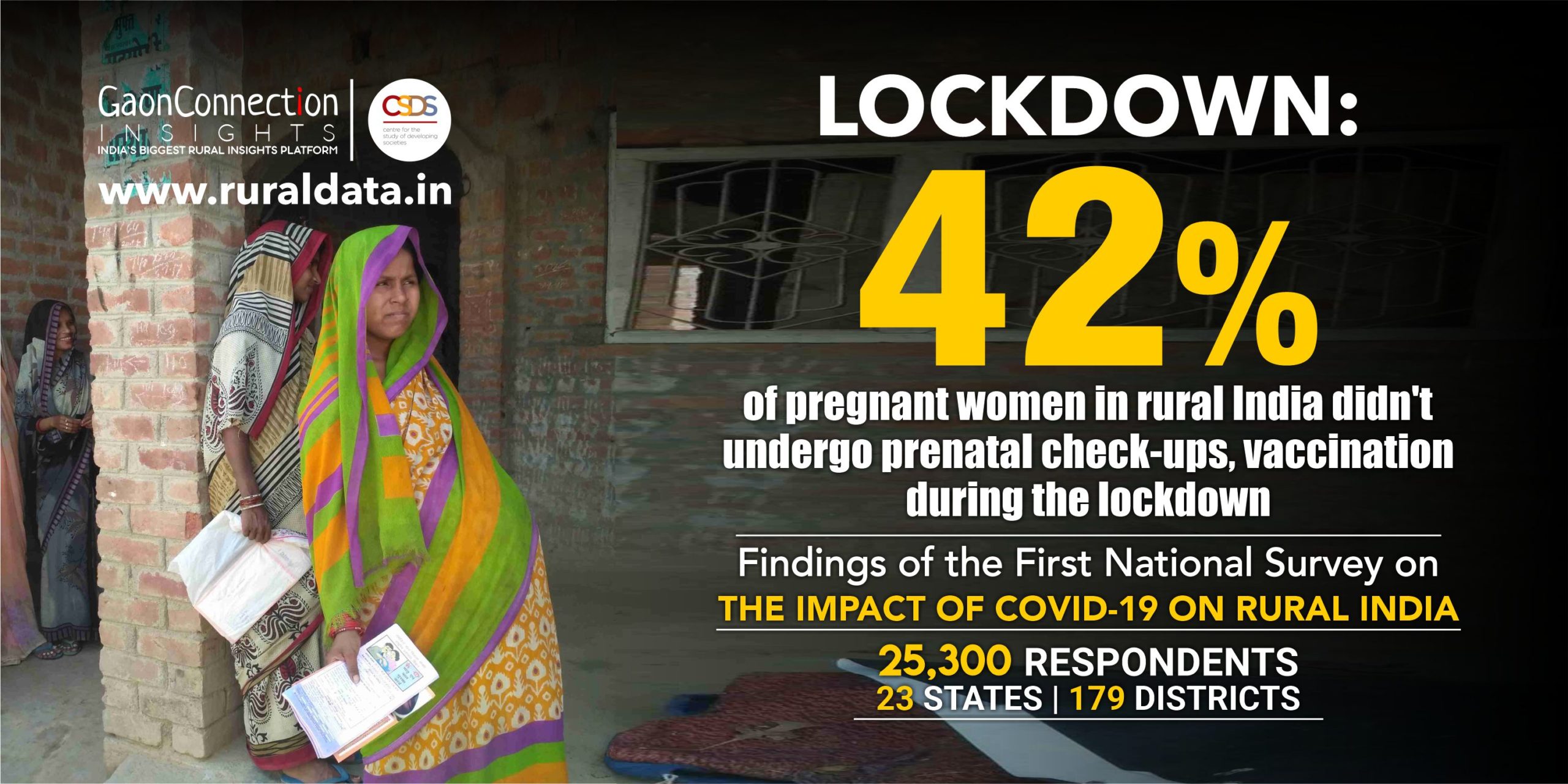

To understand the impact of COVID19 lockdown on the health of pregnant rural women, Gaon Connection, as part of a first ever national rural survey, interviewed households with pregnant women to document if these women were able to access prenatal checkups and vaccination during the lockdown. The Gaon Connection Survey with 25,371 rural respondents spread across 179 districts in 23 states was designed and data was analysed by the New Delhi-based Centre for Study of Developing Societies (Lokniti-CSDS).

The survey found around one in every eight respondent households reported having a pregnant woman in the household. Nearly three-fifth of such households (58 per cent) confirmed prenatal checkups and vaccinations of pregnant women. However, 42 per cent didn’t undergo any checkups or vaccination, or couldn’t confirm it confidently. Only a little over half of all households with children claimed with certainty that child vaccination happened in their area during the lockdown.

Interestingly, 40 per cent of households with pregnant women in green zones across the country did not receive any checkups or vaccination, followed by 36 per cent in orange zones, and 56 per cent in red zones.

As per the orders of the Union ministry of health and family welfare, the prenatal checkups and vaccination of pregnant women were to take place at primary and community health centres. However, it was found these services were largely ignored during the lockdown.

The maternal health scenario in the country is already poor. According to the Pradhan Mantri Safal Matritva Abhiyan, around 44,000 women die every year due to pregnancy-related complications whereas 6.6 lakh children die within 28 days of birth.

“It’s not surprising that maternal care in rural areas has been affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pregnant women are being discouraged from reaching hospitals during this time of the pandemic,” Sulakshana Nandi, national co-convener of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (People’s Health Movement), Raipur, Chhattisgarh, told Gaon Connection.

“Vulnerable groups such as tribal communities are largely dependent on the government hospitals for health services. These have now been converted into COVID-19 facilities. Given services in these public hospitals is affected, these marginalised groups have suffered the most in the lockdown,” she added.

The Gaon Connection Survey, which has also analysed state-wise data, shows Rajasthan at the top with 87 per cent households with pregnant women confirming receiving prenatal checkups and vaccination in the lockdown. This is followed by Uttarakhand (84 per cent) and Bihar (66 per cent). At the bottom comes West Bengal with only 29 per cent pregnant women confirming required health checkups followed by Odisha (33 per cent).

All these survey findings, including impact on the health, have been put together in the form of an exhaustive report – ‘The Rural Report: The impact of COVID19 on rural India’. The report is available on the website of Gaon Connection Insights.

There are several stories of pregnant women’s inability to access healthcare during the lockdown, leading to either a miscarriage, or delivering a baby on the roadside. For instance, after covering two-kilometre on foot, three-month-pregnant Shivangi Singh reached the community health centre in Itaunja village in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, for prenatal checkup and vaccination. But, was turned way and told prenatal checkups were suspended during the lockdown. She was neither examined nor given the tetanus shot, which is a necessity during the pregnancy.

“There must be four antenatal checkups for a pregnant woman in the complete nine-month course. As per the Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan, every gynaecologist must help out women with one OPD on every 9th of a month. However, this is not happening because of this coronavirus situation,” Hemashree Patel, a Mumbai-based gynaecologist told Gaon Connection.

“Pre-natal checkups, supposed to happen every month, are not happening. We check the blood pressure of the patient every month, a screening factor for gestational hypertension; we check the mother for anaemia in case the haemoglobin is low,” said added.

According to her, there’s also a risk of diabetes in pregnancy. “We conduct a glucose challenge test in 20 weeks. If these are not happening, then we miss out the risk assessment which must be done every month. As a consequence, maternal deaths could be reported, and the development of the child would get affected,” she warned.

According to UNICEF, the first 1,000 days of life — the time spanning roughly between conception and one’s second birthday — is a unique period of opportunity when the foundations of optimum health, growth, and neurodevelopment across the lifespan are established. Yet too frequently in developing countries, such as India, poverty and its attendant condition, malnutrition, weaken this foundation, leading to earlier mortality and significant morbidities such as poor health, and more insidiously, substantial loss of neurodevelopmental potential.

COVID19 pandemic has multiplied this risk manifold, as a large number of pregnant women failed to access the regular healthcare in the lockdown.

“As of now, pregnant women are being asked to come for checkups only in the ninth month [most women deliver in the ninth month], and not to come during the fourth and seventh months. But if the checkup is performed only in the last month and if they were at risk, how would doctors treat them?” wondered Renu Singh, 38, who works as an ASHA Sangini at a community health centre in Itaunja in Lucknow of Uttar Pradesh. An accredited social health activist (ASHA) is a community health worker instituted by the health ministry as a part of the National Rural Health Mission.

Both ASHAs and auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs, a village-level female health worker) were involved in COVID-19 duties, thus, health services in rural India suffered during the lockdown.

Timely delivery of health services is as important. “Prenatal checkups and vaccination is not like a knee replacement that could be postponed for later. In pregnancy, you need to get medical care on time. Its consequences will only show up after a year or two when mortality would increase,” Dipa Sinha, assistant professor, Dr BR Ambedkar University, Delhi, told Gaon Connection.

“If 40 per cent of women failed to get medical care in the lockdown, it is worrying. Many states are also facing new lockdowns; women who have to undergo checkups may again get affected,” she added.

Status of supplementary nutrition

Indian government’s Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) is the world’s largest programme for early childhood care and development. It offers six services: supplementary nutrition, preschool non-formal education, nutrition and health education, immunisation, health checkup and referral services, through 1.36 million functional anganwadi centres spread across all the districts in the country (as of June 2018). Pregnant women are also enrolled as its beneficiaries and provided extra nutrition supplement through anganwadis.

However, this service too suffered during the lockdown, as anganwadis were shut down in mid-March due to COVID19.

Gaon Connection Survey found over half of households with pregnant women reported getting extra rice-wheat from the government during the lockdown. Almost 34 per cent such households said they did not receive the additional grains, whereas 11 per cent could no answer with certainty.

State-wise data analysis shows Rajasthan reported maximum number of households with pregnant women who received additional grains from the government at 93 per cent, followed by Uttarakand at 87 per cent and Madhya Pradesh at 62 per cent. The lowest three states are West Bengal (33 per cent), Bihar (34 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (50 per cent).

“During pregnancy, additional nutrients play a big role. If nearly half of the pregnant women didn’t get additional ration, then it’s extremely worrisome,” said Nandi. “Many states have adopted Ghar Pahuch Sewa, in which, anganwadi workers visit door-to-door and advise nutrition chart to pregnant women. This is happening in some states but not all. In Chhattisgarh, hot cooked meals were given to pregnant women that included dal (pulses), sabji (vegetables), chawal (rice), but now only powder is being given,” she added.

What about kids’ health?

Apart from women, immunisation of children also suffered during the lockdown. Gaon Connection Survey found about 55 per cent respondent rural households reported vaccination of children during the lockdown.

A state-wise analysis of these households indicates Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh were the worst performers with 13 per cent and 39 per cent households reporting vaccination of children happened in their villages. Meanwhile, Punjab, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan did extremely well on this count with over four-fifths of households with school going children claiming child vaccination took place in the lockdown.

According to the Gaon Connection Survey, 46 per cent households with kids did not receive any dry ration for children, which can be a major concern for the health of these kids as malnutrition is a major concern in the country.

As far as state-wise ration or meals for kids is concerned, Uttarakhand, Jammu & Kashmir, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan seem to have performed exceptionally well with over four-fifth households reported receiving food during the lockdown.

Health services suffer in lockdown

The Gaon Connection Survey also tried to ascertain the level of difficulty encountered by households with respect to obtaining medicines or seeking medical help during the lockdown.

Respondents were asked how often they or a member of their household went without necessary medicine or medical treatment during the lockdown due to lack of money or resources. Around two-fifths (38 per cent) responded by saying that they had encountered this problem either many times during the lockdown or sometimes.

Around 22 per cent, or one in every five households, said that they had felt the need to visit a doctor or a hospital during the lockdown, and at least two-third of them did not delay their visit and one-fourth did.