Despite the early morning chill, Chinmay Sawant of Kiraksal sets out every morning to roam around his village. Soon, he is joined by young boys and girls of the village, all of whom are armed with binoculars and hats. They spend a couple of hours bird watching and writing down details of the species they spot. Winter is the best time to study migratory birds, the youth say.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, inhabitants of Kiraksal in Maharashtra, about 275 kilometres from the state capital Mumbai, have been regularly documenting flora and fauna in their village located in Satara district.

Not only do they keep a tab on the bird species in their area, the youth also participate in the Great Backyard Bird Count, where thousands of birdwatchers across the world record the birds they spot on specific four days of the month.

Documenting bird species is not the only feather in Kiraksal’s cap. Since 2012, the village has seen remarkable progress in conservation of water, wetlands and wildlife. According to the census of 2011, there were 1,476 inhabitants in the village, which has increased to about 1,800, the villagers say.

Due to the sustained efforts of its youth, Kiraksal, spread over 1,802.64 hectares, and surrounded by hills, wetlands and forests, has become a hub of biodiversity activities. And in the past three years of the pandemic, they put in extra hours at work to safeguard their environment.

“In March 2020, there were only about 50 birds that we had identified in Kiraksal. Today there are 203 documented species of birds here,” 21-year-old Sawant, who is in his final year of studying fisheries science, told Gaon Connection. He has been instrumental in bringing the village youth together for conservation related activities.

Last month, in December 2022, Sawant also made an online presentation titled Youth as Seeds of Transformation, to the United Nations Biodiversity Conference — COP 15, or the 15th Conference of the Parties conference — held in Montreal, Canada from December 7-19.

Sawant outlined how the rural youth in Maharashtra, particularly in his village Kiraksal in Man taluka of Satara district, was actively taking part in the documentation of the flora and fauna of the region. A number of village children regularly participate in a bird census and maintain a record of birds they spotted.

In his presentation, the 21-year-old village youth, informed the audience about the aim and vision of the Maharashtra chapter of the Indian Youth Biodiversity (IYBN) Network, an official chapter of Global Youth Biodiversity Network, that has young villagers like him wanting to create a positive impact on biodiversity issues and prevent the loss of biodiversity.

The efforts of rural youth of Kiraksal village in Maharashtra were applauded by the international community at COP 15.

Also Read: The fragile butterfly is as important as the mighty tiger

Putting the lockdown to good use

In 2019, the Kiraksal Biodiversity Management Committee was formed and along with it the People’s Biodiversity Register (PBR). This was the initiative of the National Biodiversity Authority, an autonomous and statutory body of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, Government of India. The PBR documents flora, birds, butterflies, animals and insects, besides indigenous traditions of music and dance, food crops and so on.

Due to the sustained efforts of its youth, Kiraksal, spread over 1,802.64 hectares, and surrounded by hills, wetlands and forests, has become a hub of biodiversity activities.

However, real work in this direction happened in 2020, when Sawant, who was studying at Ratnagiri (about 200 kms from Kiraksal), reached his village. “I reached Kiraksal in just the nick of time, before the lockdown was announced in March 2020. I had travelled there to my grandmother’s thinking I would be there just for a few days,” he recalled. He ended up spending eight months there between March and November.

Armed with a binocular and in the company of another nature lover Vishal Katkar, Sawant would spend all day, from morning to evening, wandering the forests and hills around their village, watching birds, and in the case of Katkar, butterflies.

“We were soon joined by my sister Anushka who was studying in the twelfth then and Kuldeep, who grazed cattle and knew the landscape inside out,” Sawant said.

Also Read: ‘Biodiversity loss and climate change need to be tackled together as both reinforce each other’

Soon, young people in the village, intrigued by the binoculars, began to join their birding excursions. “It seemed like a good time to involve the village people in an activity during the lockdown. And, bird watching was possible to do safely as we were spread out and not in such close proximity,” Sawant told Gaon Connection.

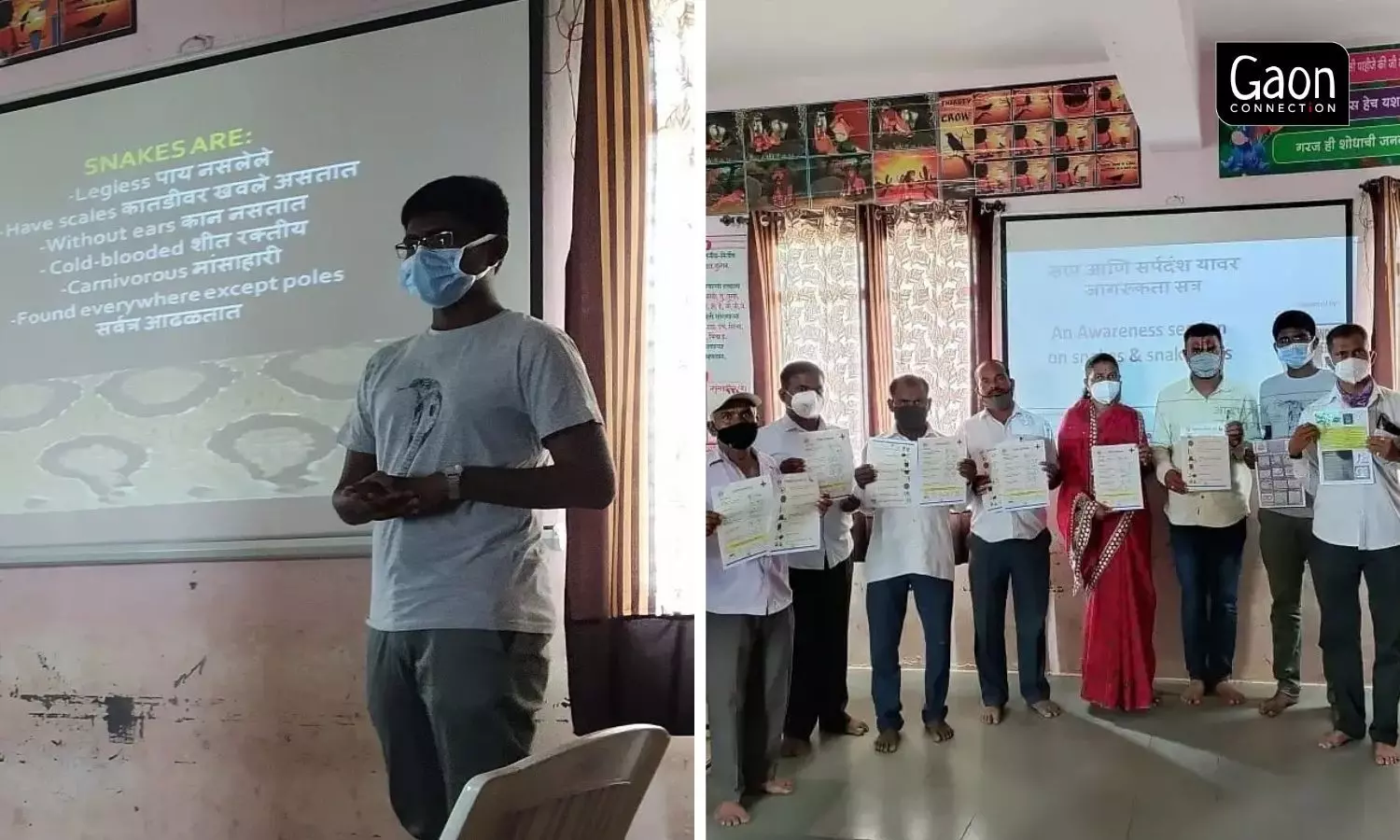

With the permission of Amol Katkar, who was sarpanch (village head) then, Sawant began to organise short presentations to the village inhabitants. He showed pictures of the birds they had spotted in and around the village; spoke about the flora and fauna; encouraged young people to record what they had seen.

In February 2021, Kiraksal village took part in the Great Backyard Bird Count (where thousands of birdwatchers across the world record the birds they spot on specific four days of the month). In Kiraksal about 15 young people, many of them school children, took part.

“Now, many of them note down the colour of the birds they see, where they saw them, and the date and time of the spotting,” Sawant said.

In 2020, between November 5 and November 12, bird week was observed for the first time. It was the week that fell between the birthdays of ornithologist Salim Ali and wildlife conservationist Maruti Chitampalli. “Maharashtra is the first state to celebrate Bird Week in 2020,” Sawant said with pride.

Also Read: Vultures are nature’s eco-warriors

The great backyard count in Kiraksal

In February 2021, Kiraksal village took part in the Great Backyard Bird Count (where thousands of birdwatchers across the world record the birds they spot on specific four days of the month). In Kiraksal about 15 young people, many of them school children, took part.

“We spotted 70 species of birds in the different habitats of the village, many of them migratory birds. This also included the Laggar Falcon which is rarely sighted there,” Sawant said.

It was at that time that Early Bird India, a part of the Mysuru-based Nature Conservation Foundation (a non-governmental wildlife conservation and research organisation), distributed 25-30 pocket guides on the birds of Maharashtra as well as four sets of posters of birds in different habitats, all in Marathi, to Kiraksal. Early Bird India develops innovative and multilingual educational materials to help children explore the birdlife in their villages, towns and cities.

“Having these colourful bird guides has encouraged the children further to document the rich flora and fauna of the village with its scrub forests, hillsides, wetlands and waterbodies,” Sawant said.

Water conservation works support biodiversity

Documenting bird species is not the only feather in Kiraksal’s cap. Since 2012, the village has seen remarkable progress in conservation of water, wetlands and wildlife. According to the census of 2011, there were 1,476 inhabitants in the village, which has increased to about 1,800, the villagers say.

Before 2012, the village struggled with shortage of water. “Tankers supplied water to us. But the last tanker rolled in in 2012, after which we have never had to struggle for water,” Amol Katkar, the former sarpanch and now an active member of the panchayat, told Gaon Connection.

That was because of the intervention of people such as Avinash Pol (fondly called panyacha doctor or the water doctor) and Popat Rao Pawar (who transformed his village, Hiware Bazar into a model village in the state), and the non-profit Pani Foundation, Katkar said.

In his presentation, Chinmay Sawant, informed the audience about the aim and vision of the Maharashtra chapter of the Indian Youth Biodiversity (IYBN) Network, an official chapter of Global Youth Biodiversity Network, that has young villagers like him wanting to create a positive impact on biodiversity issues and prevent the loss of biodiversity.

More than 500 volunteers from the village worked day and night to build bunds, dig trenches and other receptacles for rain water harvesting in Kiraksal, and water shortage ceased to be an issue.

With water conservation taking effect, the flora and fauna of the area also began to flourish. “Birds, butterflies, rabbits, foxes and wolves… we began to sight a lot more of them in our forests and hills surrounding the village,” Katkar said.

For Amol Katkar and Sawant and the increasing number of nature lovers in Kiraksal, the work around the village’s bio-diversity has come to assume great significance and importance.

The new year has brought with it more resolutions and projects, like Project Indian Wolf. “In August 2021, we observed the International Wolf Day in Kiraksal, which was greatly appreciated by researchers globally. The Indian wolf is the main predator in these parts, and we will document its movement, habitat and so on,” Sawant explained.

More than 500 volunteers from the village worked day and night to build bunds, dig trenches and other receptacles for rain water harvesting in Kiraksal, and water shortage ceased to be an issue.

The dream is to make Kiraksal a centre for birdwatching, where people from all over the country will congregate. “We will provide volunteers training in scientific documentation of the flora and fauna, work closely with the forest department and non-profits and invite bird experts to share their expertise with us,” Sawant said.

Also Read: The Tale of a Striped Monk

The ripple effect

Former sarpanch Katkar hopes that working in these matters closely with local communities will further enrich the biodiversity, and perhaps make Kiraksal a centre for eco-tourism.

“The ripple effect of getting aware of our environment has led to other positives. We built bathrooms for the children of our school. The water conservation efforts have paid off and instead of the single season of harvest, we now have two. Irrigation has improved and with more greenery, so has the fodder situation. We are producing nearly 3,000 litres of milk a day. Poultry farming by women has picked up. And, importantly, young people are not so quick to leave the village and go away, in search of livelihoods elsewhere,” Katkar said.

Talking to Gaon Connection about new year resolutions, Katkar said there were several plans in the pipeline. “We want to improve the educational facilities in the village and actively work on ending alcoholism. And we will surely do it,” he concluded.