V Swaran, Prachi D Patil and A Ravindra

There was palpable excitement among the community as they shared their findings and curiously listened to each others’ experiences. It was the Ides of March of 2022 — apparently the day the ancient Romans settled their debts.

This small group consisting of the custodians of agrobiodiversity, development professionals, independent researchers and veterans from the National Agriculture Research System also had some debt to repay — to India’s indigenously evolved agricultural practices.

The gathering in Hyderabad was convened to deliberate on the results of an exercise documenting India’s indigenous multi-cropping systems (IMiCS) of rainfed areas. Multi-cropping in this particular context is more than its definition of having more than one harvest in a year. The indigenous component makes it a profoundly contextual socio-eco-cultural web.

Farmers have developed IMiCS over many centuries following the local agro-ecological-agroclimatic conditions and needs.

IMiCS are no single family of practices but include line sowing and broadcasting, cultivation on traditional agricultural fields and shifting cultivation, traditional agronomic practices and the application of modern implements.

Also Read: Post-harvest cold storage unit puts smiles back on the faces of farmers in Odisha

It is also about the design across space and time through the effective use of sunlight between crops of different heights, the utilisation of crop residues for providing nutrition to successive crops, the mutual dynamics between companion crops, the intraspecies diversity, provision of food, feed and fodder.

The exploratory study exercise coordinated by the Hyderabad-based resource support and public policy think-tank WASSAN was an outcome of encouraging experience from a comparative analysis between the Navadhanya IMiCS of Rayalaseema region, Andhra Pradesh against monocropping systems.

Specific characteristics of Navadhanya, like extended periods of soil cover and crop harvest, stand in direct contrast to mono-cropping, where soil could remain uncovered even for more than half the year with a one-time harvest and, of course, a single crop.

Ten multi-cropping systems, including an extinct one, were documented through this study, covering geographies having 400 mm annual rainfall to about 3,000 mm (see map).

The documentation process included cultural facets and historical changes in the crop combination of each cropping system. Cropping layout, crop calendar, income estimates from produce, climate risk, and contribution of nutrition to the soil, livestock, and humans were also estimated during the exercise. Based on these parameters, some common design principles were observed among the IMiCS’.

For instance, almost all the systems follow one-time sowing with multiple harvests. Apart from providing a steady supply of produce (catering to the needs of food and often fodder/feed also) from the farm, this reduces the risk of crop failure as the harvest of one crop is followed by others.

Also Read: Kharif paddy lost to drought, no resources to sow rabi wheat, say farmers in Jharkhand

Long-duration crops like castor and cotton are grown alongside short-duration creepers and climbers, effectively utilising space and sunlight.

Farmers’ practical wisdom and ingenuity are also visible in the various other aspects of the IMiCS. For instance, in Ponamkuthu of Wayanad, Kerala, sowing requires particular skill to ensure that the seeds are evenly distributed and that optimal quantity is used. Selection of border crops is based on their application as varied as windbreakers (bajra/Jowar), breaking pests infestation (castor), deterring crop raids by animals etc.

Almost all the systems have millets, pulses and oilseeds in their primary crop mix, reflecting the importance of self-sufficiency and dietary diversity.

Also Read: Despite higher MSP at govt procurement centres, farmers prefer selling paddy to private traders

What lies ahead

With wheat and rice cultivation hit badly by heatwaves and drought, IMiCS could address some of the challenges farmers face, especially those in rainfed areas.

The wealth of information generated by this exercise has created a renewed interest in IMiCS’ among organisations leading to its experimentation in the fields.

This includes the efforts to bring back the long-defunct twelve-crop system of Baradhanya in Western Maharashtra by the Pune-based NGO Agro Rangers. Non-availability of indigenous seeds is challenging in revitalising and rejuvenating these multi-cropping systems. Even in places where seeds are available, the original diversity has diminished.

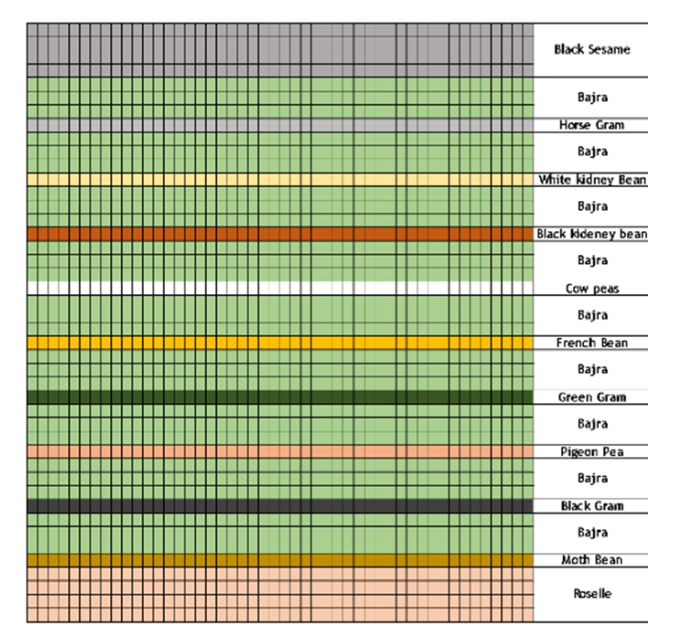

Image: A representative illustration of the Baradhanya cropping system.

Image courtesy of Agro Rangers

Efforts are also underway to generate evidence on the merits of IMiCS through field trials by each. Governments and the NARS system also have a heightened interest in understanding such hitherto marginal farming practices.

While the biofortification of cereals is seen as a means of addressing the hidden hunger, a less technical but equally scientific and cost-effective means for achieving the same could be through the agrobiodiversity of IMiCS.

This is also of importance in the context of the fodder crisis faced by dairy farmers due to the huge disparity in the demand and supply of quality fodder.

Currently, some major agenda-setting organisations of the global agri-food system appear to be rethinking how food is produced and consumed. Importantly there is a growing realisation that transformation is not just about a change in crops or practice but of institutional mechanisms and public policy as well.

From the 7-crop system of Rammol in Bhuj to the nearly 40-crop system of Kurwa in Jharkhand, IMiCS’ are waiting to be explored in the context of agroecological transformations. And there are platforms like the ongoing UN Decade of Family Farming 2019-2028, the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration 2021-30, and the upcoming International Year of Millets 2023 where this theme could be applied to be of a global (south) relevance.

Swaran is a Research Associate at WASSAN and a PhD Candidate at CTARA, IIT Bombay. Prachi is with WASSAN as Programme Officer- Water Resources. Ravindra is the Executive Secretary of WASSAN and has been working on the issues of rainfed agriculture. This study was undertaken as a part of the Flagship Project 6 of the University of Cambridge’s TIGR2ESS programme. Views are personal.