Palamu, Jharkhand

Kuldeep Ram owns about two katha (1.27 of an acre) in his village at Duba in Palamu district in Jharkhand, on which he traditionally grows paddy.

But he has left that land uncultivated this year and is instead waiting at the Daltonganj railway station, about 20 kilometres from his village, to board a train to Sasaram, in Bihar. There are about 20 others like him doing the same.

“If it had rained, I would not be going anywhere. I would have enough work to do back in my village,” the 25-year-old farmer told Gaon Connection. Instead, Kuldeep is migrating to Sasaram with his uncle to work as a construction labourer. “How long can I sit at home? I have three children to feed,” he said.

Like Kuldeep, Anil Ram has also been forced to step out of his Duba village. The 21-year-old, who is stepping out in search for the first time, is worried. He is a victim of polio and knows his employment opportunities are limited.

Anil owns 2.5 katha of land where he cultivates paddy and maize during the kharif season and also works as a cowherd. But he has been unemployed for the past few months.

“When there is farming, people use cowherds for the animals to ensure they do not harm the crops. But, this year there is no farming anywhere… the animals don’t need herding. So I have no work,” Anil told Gaon Connection.

Kuldeep (left) migrating to Sasaram with his uncle to work as a construction labourer.

Also Read: Trouble in the Rice Bowl of Bengal

It is the southwest monsoon season but Jharkhand is facing drought-like conditions. Between June 1 and August 16, the state has recorded a rainfall departure of minus 36 per cent. Of the total 24 districts in Jharkhand, only one district (West Singhbhum) has reported ‘normal’ monsoon rainfall so far.

All the other districts have deficient rainfall ranging from minus 72 per cent to minus 25 per cent. Palamu district, where Kuldeep Ram and Anil Ram live, has deficient rainfall of minus 52 per cent.

A shortage of rainfall is having a direct impact on paddy cultivation in the state, which is the main crop of the state. Ideally, paddy seedlings are ready by the end of June and ready to be transplanted in July. Timely monsoons ensure employment to farmers and agricultural labourers.

Anil Ram waiting for the train at Daltonganj railway station in Palamu district, Jharkhand.

“I hope to find work constructing walls, plastering or anything else which has less movement,” Anil said. For him and others like him who are moving out of their villages, an assured wage of Rs 350 a day is an attractive proposition when compared to no income at all in their fields.

A similar situation prevails in the neighbouring states in the Indo-Gangetic plains in India where some key paddy producing states have received deficient monsoon rainfall.

As part of our new series – Paddy Pain – Gaon Connection reporters travelled across the key paddy producing states to document the impact of deficient monsoon rainfall on the paddy crop this year. And the reports they have come back with seem worrisome, as paddy farmers are reportedly staring at huge crop losses.

And these local crop losses have a global impact as a drop in rice production in the country is likely to disrupt global food supply, as India is the world’s top exporter of rice.

The first story of the ‘Paddy Pain’ series was from Uttar Pradesh; the second from West Bengal; the third from Bangladesh; and this report from Jharkhand is the last of the series.

Drop in paddy sowing

According to the latest data released by the central agriculture ministry, the state government has set a target to sow paddy in 1.8 million hectares in the kharif season, out of which sowing has happened in only 0.27 million hectares so far. Last year, this time, 0.75 million hectares of land had been readied by now.

“The state has received good rainfall in the first week of August, and the sowing coverage has increased in many districts. Yet, this time we are expecting an overall 50 per cent decrease in paddy sowing,” D N Singh, chief scientist, dry land agriculture, regional centre, Birsa Agriculture University, told Gaon Connection.

“The condition in districts like Palamu, Garhwa, Gumla, Sahebganj is the worst, as there the cultivation can decrease by 80 per cent,” the scientist added.

People are definitely affected this time as 88 per cent of the state (geographical area) is dependent on rainfall for agriculture, said P K Singh, scientific advisor to the Vice Chancellor at Birsa Agricultural University.

“Cultivation in Jharkhand means paddy, if agriculture is not good then farmers, and agricultural labourers will migrate for livelihood. The rainfall in the coming few days is crucial for paddy sowing,” he added.

On being contacted, an agriculture officer told Gaon Connection on condition of anonymity that on July 26 there was a meeting with the state chief minister at the Nepal House where he was explained what can be done in case drought like situation prevails.

“We systematically presented the conditions of all districts including Palamu… we are currently monitoring the rainfall data… so far we have not got any instructions, but very soon a decision will be taken. The moment we get any instruction, we will implement it in the ground,” the official said.

Migrant workers from Palmu board their train to Sasaram, Bihar.

Men migrate, women left behind with no earnings

Forty-year-old Poonam Devi, a resident of Mahugawan village in Palamu district, about 10 km from Daltonganj, is alone at home with her 10-year-old son. Her husband and two brothers have gone to Bengaluru, about 1900 kilometres away to Karnataka in south India, in search of employment.

“By sowing paddy and working in a maize field, we used to earn four to five quintals (1 quintal = 100 kg) of grain. This is enough for the year,” Poonam told Gaon Connection. But this year, there was no work for them.

“A fortnight ago I got work for two days in the maize field and I earned Rs 250 a day. After that, I haven’t found any job,” she said.

Poonam has neither a ration card nor a bank account, and will have to run the house until her husband returns home. When asked how she manages her house, she kept quiet for some time and then said, “Somehow it is going on, I do whatever job I get.”

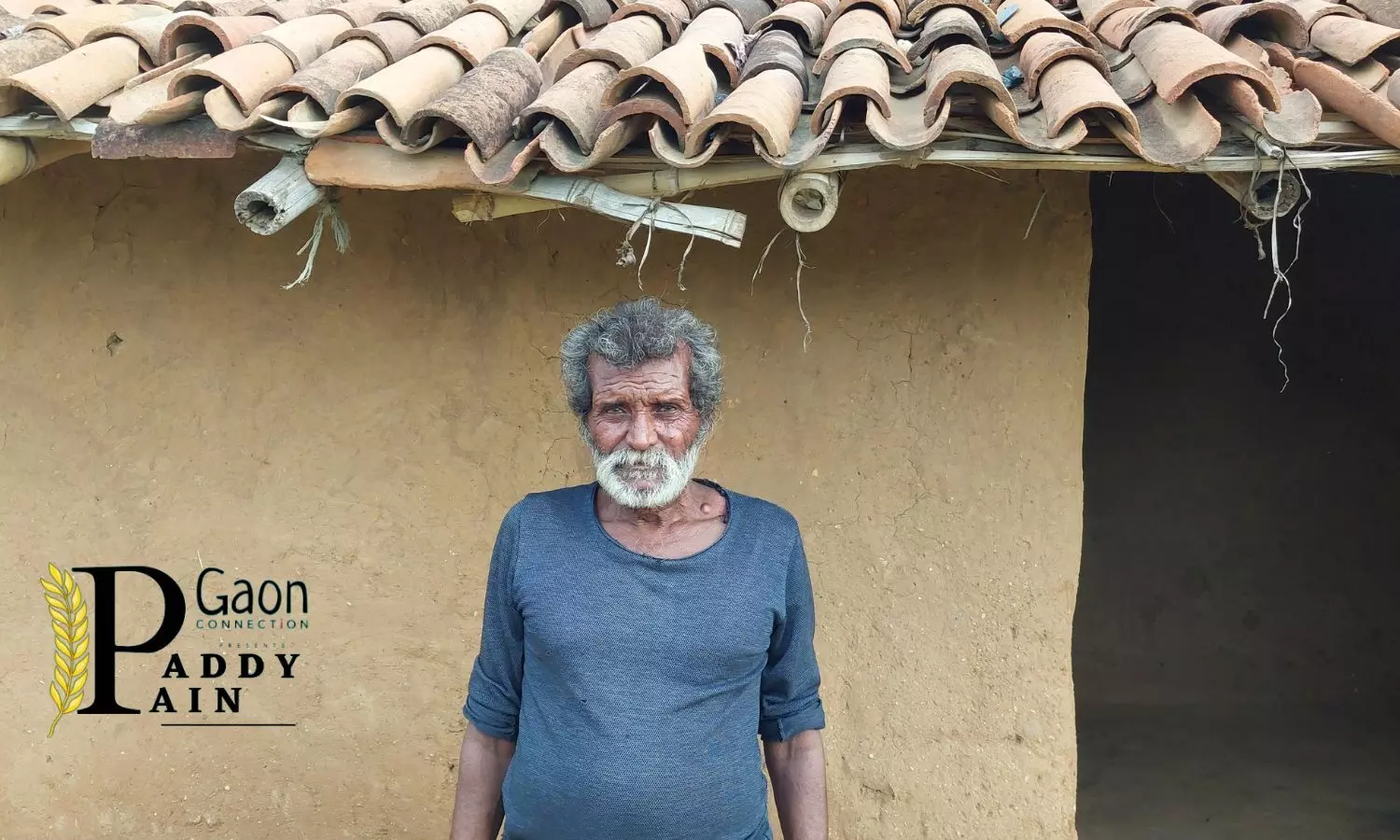

Suresh Bhuiya, 65, a rickshaw puller who worked as a tenant farmer in the monsoon season every year.

This year Suresh Bhuyiya, who lives in Bhuiya tola (hamlet) near Mahugawan village, had invested around Rs 9,000 for cultivating paddy on a nearby landowner’s field but lost his money due to the delay in rainfall.

The 65-year-old is a rickshaw puller who works as a tenant farmer in the monsoon. This year due to a lack of rain, his two sons and a son-in-law have gone to Bengaluru to work as construction labourers while his wife and daughter have gone to Mohania, Bihar to work on paddy fields.

“Usually, everyone in this tola is busy farming in the rainy season. There is so much work,” Suresh told Gaon Connection. There are about 2,000 inhabitants of this tola and while they do migrate to find work, it is never during the monsoon, he added.

Panna Devi, who also lives in the tola, works as an agricultural labourer. The 45-year-old has six children, and after the death of her husband from tuberculosis (TB) last year, she is the sole breadwinner of her family.

In the first week of July, Panna Devi, went to Bihar to sow paddy, leaving her children under the care of her eldest daughter (and neighbours) who is just 11 years old. But, she returned in a week. “I have small children, I can’t stay out for a longer time,” she told Gaon Connection.

Panna Devi (left) with her children, the eldest (right) takes care of five of her siblings.

Panna said she started sowing paddy at five in the morning and worked up to 11 am. Then she started again at 3 pm and continued till 6 pm. “It’s a lot of work, and if it’s not sunny, we even work in the afternoons,” she said.

Even after working for almost ten hours a day, what she earns is very less. “They didn’t pay us cash, they paid 12 kilos of rice per day,” said Panna.

“I have never seen Sawan [July-August] so dry. This year there’s no rain at all, there is nothing to eat,” she said.

Also Read: Fear of drought looms large over Bundelkhand; paddy and pulses crops affected

Universalise the PDS

“There is no work anywhere, we won’t get anything [ration] from the government also, how will I raise my children,” Panna asked. She too has no ration card and with the drought looming large she is worried.

Under the National Food Security Act of 2013, every ration cardholder under Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY), is entitled to 35 kg of food grains per family per month and priority households are entitled to 5 kg of food grains per person per month.

“The biggest issue in the PDS (Public Distribution System) right now. It is still based on the 2011 census and hence a large proportion of families who should be eligible are excluded from the PDS. Given the drought-like situation, the government needs to universalise the PDS to ensure the food security of the state,” Siraj Dutta, a Ranchi-based activist associated with the Rights to Food campaign, told Gaon Connection.

In 2020, in the wake of the pandemic, the Centre launched the Pradhan Mantri Gareeb Kalyan Anna Yojana (PM-GKAY) – a food security welfare scheme. Under this scheme, all ration cardholders are entitled to an additional 5 kg grain per person every month, free. The scheme ends in September this year, but experts believe it should continue with the scheme.

“With a possible drought-like situation in the coming months, the government should continue the PM-GKAY scheme, especially for a state like Jharkhand,” said Siraj.