Maya Devi was quick to answer if accepting dowry was wrong. “Lena-dena, dono galat hai [Both accepting and giving dowry is wrong],” the 13-year-old said.

Devi dreams of growing up and joining police services to eradicate some of the social evils she observes in her village Bansa in Hardoi district of Uttar Pradesh. Belonging to a Scheduled Caste, a traditionally marginalised community, despite being a child, she was not spared from the casteist comments in her village.

“Many people say that I am a chamar [a casteist slur] and don’t deserve to study,” she told Gaon Connection. “But education is our right. Everyone should get to study,” she added.

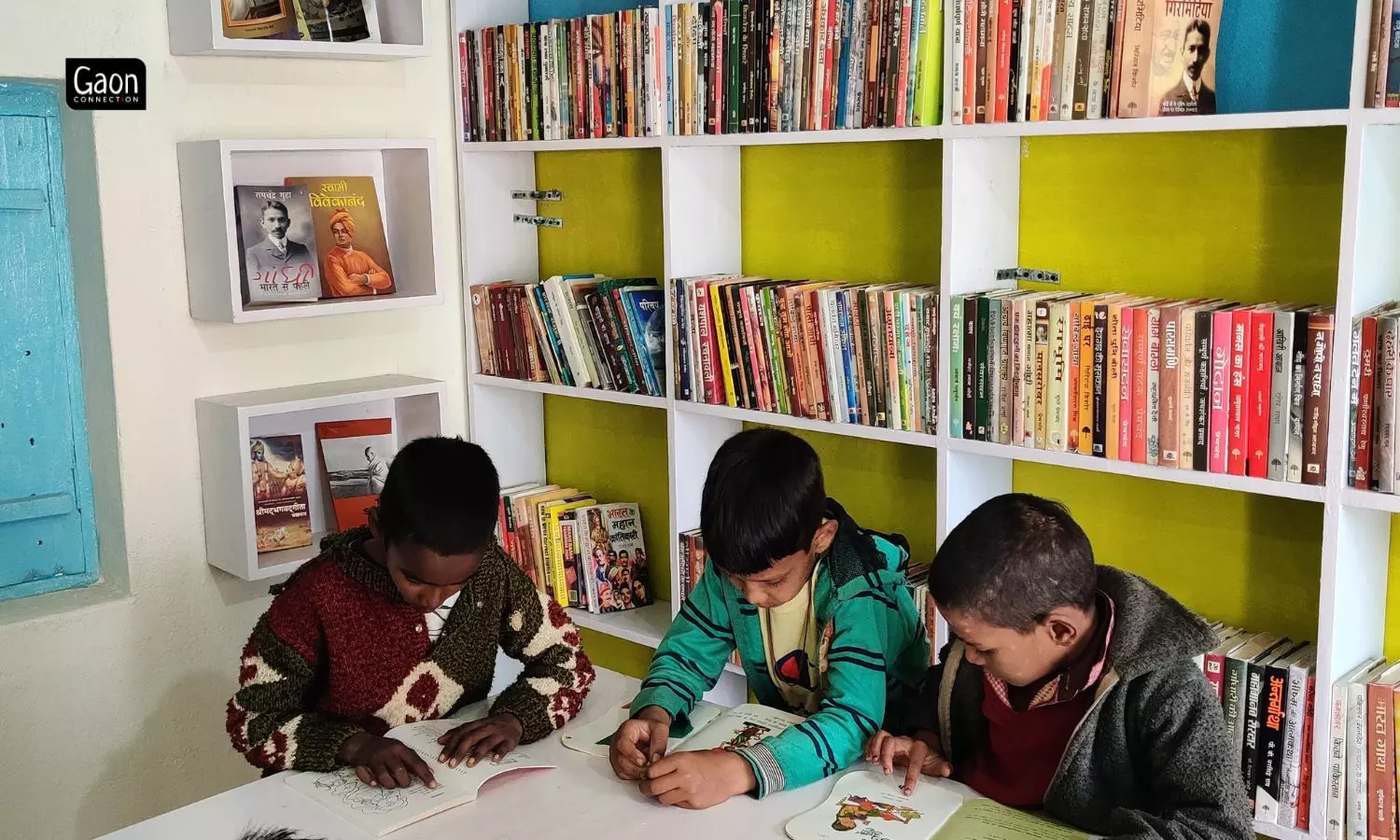

For a 13-year-old, social subjects like dowry and caste have been introduced through a community library in her village, located 110 kilometres from the state capital Lucknow.

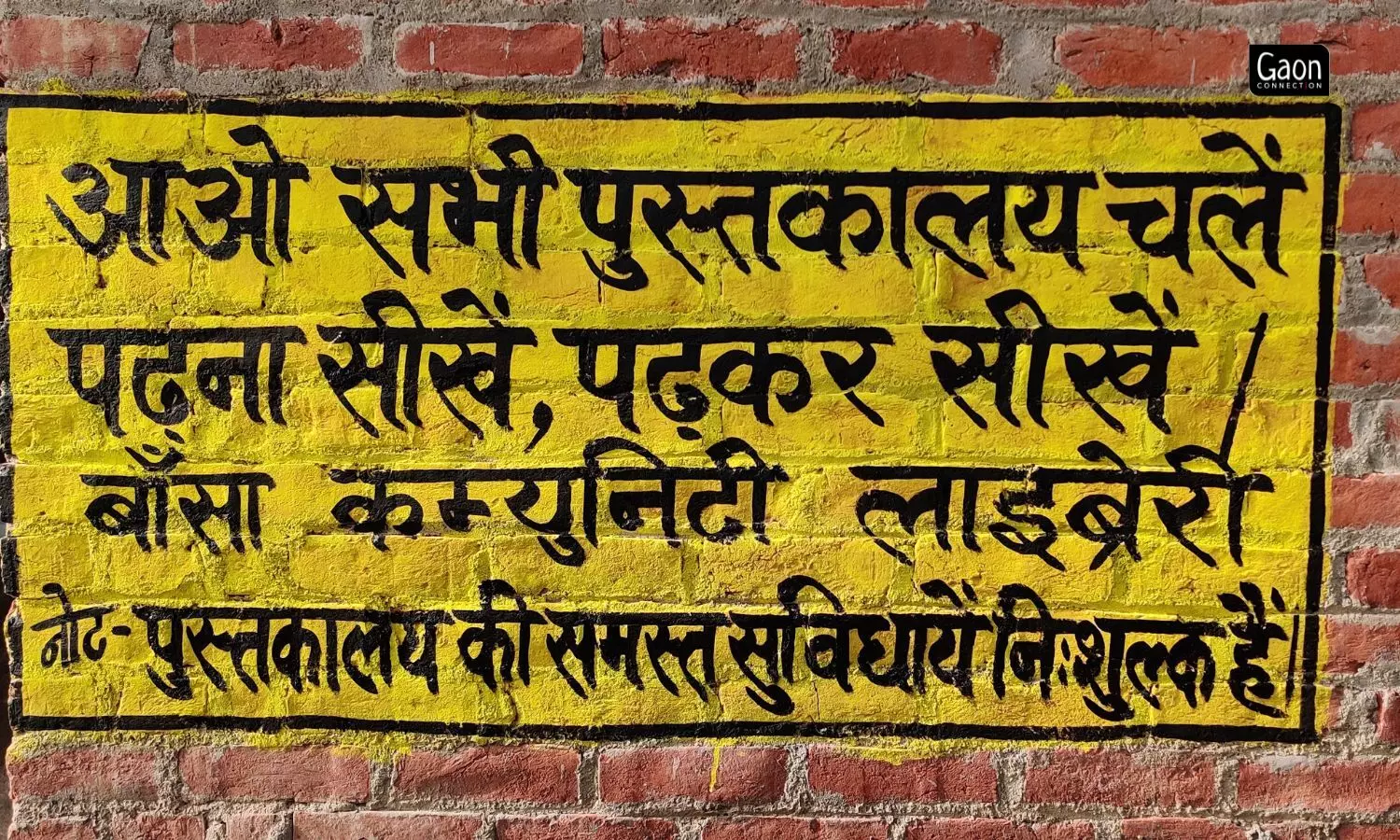

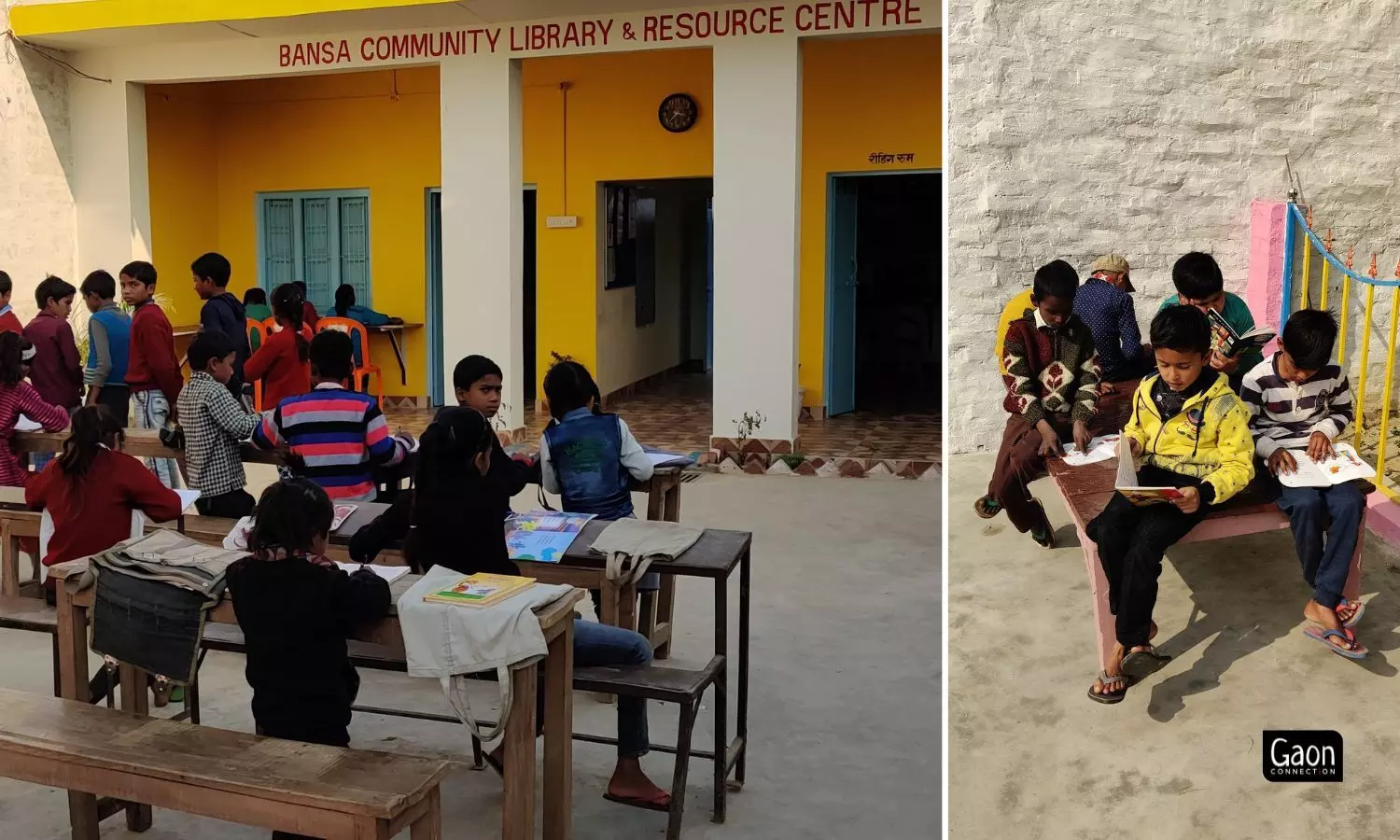

Inaugurated in the village in December 2020, Bansa Community Library is open to all — with no bar on age, gender, caste and class. The library is located within the village complex and has 1,700 registered members, both adults and children from the neighbouring villages in the district, who issue 200 to 300 books every month.

A young man, Jatin Lalit Singh envisioned a space in Bansa village — his hometown — where people could read for pleasure. And that is how the community library started, which has stirred up awareness on law, rights and rural schemes in the inhabitants of the village.

The transformation of an unused space in the temple premises to a community library.

The 25-year-old borrowed the idea of starting a community library in his village from The Community Library Project (TCLP) in New Delhi, where he volunteered on weekends while studying BA LLB [Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Legislative Law] in 2016. TCLP has set up three libraries in Delhi and Gurugram, catering to a membership of over 6,000 children and adults, seven days a week.

While volunteering with TCLP, Singh observed personality change in the children of migrant labourers visiting the library in Delhi, over a course of time. While talking to Gaon Connection, he recalled a child Daksh from TCLP to make an example.

Also Read: The Fondest Corner in a Govt Primary School

“He was a child of a labourer and was always timid when he had started coming to TCLP but I saw how his confidence grew, his interpersonal skills improved after two years of regular visits to the library. He could have a conversation with the other people in the library,” Singh recalled.

“I could only imagine how much of an impact it could create in Bansa, which has the majority of children belonging to a similar economic and social background as that of Daksh,” he added.

“Library is a level-playing field for me,” the founder of Bansa Community Library told Gaon Connection.

The community library started, which has stirred up awareness on law, rights and rural schemes in the inhabitants of the village.

A young man, Jatin Lalit Singh envisioned a space in Bansa village — his hometown — where people could read for pleasure.

“While I was growing up, reading always meant course books like that of Maths and Science but we were never taught to read for pleasure. I wanted to give that to my village,” said Singh. “There is an unequal distribution of resources in our country, this library was a small attempt to fill a small bit of that gap,” he added.

Eight-year-old Shashi Sharma, who studies in class V and regularly visits the Bansa library, had never seen so many books in her life before. Finding a world where she is introduced to new stories everyday has been exhilarating for her.

“I come every day and issue at least two books in a week to take back home and read. Maza aata hai [It is fun],” she said.

At eight, Sharma has become a storyteller to her two younger sisters — Sapna and Anjali. Her current favourite story is Aam wali chidiya.

The most difficult aspect was mobilising the community to inculcate a reading habit and read for pleasure.

“The community had issues with the library set up because it allowed all genders and castes to sit in the same room, share books and have conversations,” Jatin said.

“They worried that adolescent girls and boys spending time together could be a problem,” he added.

But over time, these issues have simmered down. “Occasionally, there might still be someone who has a problem with it but things change slowly,” he said.

When Singh had started out, he had two objectives in his mind: one — to create a reading culture and sustain it in the long run and second — to provide assistance to the students preparing for competitive exams in his village, who had to migrate out to cities like Lucknow and Prayagraj for the same.

The most challenging bit he imagined would be to acquire funding to have a quality infrastructure for a library.

“But overtime I realised that was the easiest bit,” Singh laughed.

The library was established with social media and offline crowdfunding. It has two librarians. It is open seven days a week, with extended hours on Sundays from 9 am to 7 pm.

“The most difficult aspect was mobilising the community to inculcate a reading habit and read for pleasure,” he added.

Shivangi Sharma got done with her B.Ed [Bachelor of Education] exam this June and the library was her go to place to access the practice papers of the competitive exam. If it wasn’t for Bansa community library, Sharma would have to go to bigger cities like Kanpur or Lucknow to get her hands on these practice booklets.

The two librarians have identified 11 students — seven girls and four boys — who regularly visit the library and formed a student leadership council. This council dedicates 15 minutes of their time every day for administrative assistance like sorting books and helping younger children reading the books.

The two librarians have identified 11 students who regularly visit the library and formed a student leadership council.

Everyone who is part of the functioning of the library belongs to the village community.

“It is important for the community to administer it because an outsider can’t really relate to why certain things happen and how to tackle them,” Singh said.

He continued with an example: “If I go and see that very few children have come to the library in a particular time period, it might appear to me that the children aren’t interested to read but a librarian from the community understands that it is the time for dhan ropayi [rice planting] so many children might be busy with that.”

“Though there are official timings, anybody is free to walk up and unlock the library on their own if they want to read,” he concluded.

Also Read: A million dreams are taking shape in Karnataka’s rural libraries