Lahuria Deh (Mirzapur), Uttar Pradesh

When the mercury hovers around 45 degrees Celsius in the summer months, the rocky tableland of Uttar Pradesh’s Mirzapur district sizzles, leaving people craving for water.

However, for some 1,000 odd residents of Lahuria Deh village in the district’s Hallia block, each one only gets a daily quota of 15 litres of water to meet all their water needs – drinking, bathing, washing and cooking – leaving them in considerable distress.

The water woes of this village located at the hilltop do not end here. The village is notorious as a ‘tanker’ village and no one wants to wed their children in Lahuria Deh.

Watch

“Doesn’t matter whether it’s our sons or daughters, nobody wants to wed their children here as we do not even have something as basic as water,” Vinod Kumar Yadav, a village resident told Gaon Connection.

As part of Gaon Connection‘s new series – Paani Yatra – our national team of reporters and community journalists travelled to remote villages in different states of the country to document how rural citizens are meeting their water needs in the scorching summers.

This story from Lahuria Deh village in Mirzapur is the second in the series of Paani Yatra.

Each tanker of water costs Rs 800 a day, which is paid for by the gram panchayat.

Also Read: A Midsummer Pipe Dream: Pipelines laid down and taps installed, but where is the water?

“It’s been at least 20 years that the village has been completely dependent on water tankers to meet its water needs – with daily supply limited to 15 litres per person,” Kaushlendra Kumar Gupta, the gram pradhan of Dewhat gram panchayat, of which Lahuria Deh village is a part, told Gaon Connection.

The water sources of Lahuria Deh have dried up, complain villagers, and so far no government scheme has been able to provide them with a regular water supply due to “topographical challenges”.

To put things into perspective, an average bucket that we use at home holds 10-15 litres of water. And according to the recommendations of the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, a typical metropolitan area in India is entitled to receive a quota of 150 litres of water per person per day — ten times more than what the inhabitants of Lahuria Deh get to use.

“Can you imagine living on 15 litres in the summers? The heat is so oppressive that a person needs at least 10 litres a day to only drink,” 34-year-old Sangam Lal Dharkar told Gaon Connection.

“In my childhood, there used to be a jharna (waterfall) in the forest at the bottom of the hill. But it has dried up now. Our village on top of the hill is at least teen sau (300) feet above the forest. There have been several unsuccessful attempts to draw underground water by boring,” Dharkar added.

Water tanker bills run into several lakhs

There was an undeclared emergency on April 23, when Gaon Connection visited the parched Lahuria Deh village. Villagers were scrambling for water as a water tanker attached to a tractor had brought their daily quota of water.

“I have made arrangements for seven tankers [daily] to meet the village’s water requirements but it’s just not enough,” Gupta, the gram pradhan, told Gaon Connection. According to him, each tanker of water costs Rs 800 a day, which is paid for by the gram panchayat.

However, when Gaon Connection approached the private supplier of the water tanker, it was learnt that the village is generally supplied with an average of five tankers of water per day.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows the daily expenditure on water tankers for Lahuria Deh comes to Rs 5,600. And in a month, this jumps to Rs 168,000 (one lakh and sixty eight thousand rupees). Further, in a year it would be Rs 2,016,000 (twenty lakh and sixteen thousand rupees). And this kind of money is being spent to supply water to Lahuria Deh for the past twenty years.

“Earlier, there were alternative sources of water like ponds and waterfalls but now almost 100 per cent of the drinking water is provided by the tankers that bring water from a borewell which is situated almost five kilometres downhill,” the gram pradhan added.

“The government is spending karodon rupaye (crores of rupees) in supplying water to our village through tankers. Why can’t the wise babu log (bureaucrats) devise means to ensure steady water supply at much lower costs,” Sangam Lal, a resident of the village wondered.

Vijay Narayan Singh, the sub-divisional magistrate (SDM), Lalganj, under which Lahuria Deh village falls, acknowledged the water crisis villagers face.

“The problem of water scarcity has always been here as it is a hilly area and the geology is such that the groundwater level is out of reach,” he told Gaon Connection. “There are plans afoot to construct an overhead tank at Lahuliya Deh,” he added. When asked about the details of the water supply plan and when the overhead tank is likely to be constructed, the official refused to comment.

Status of piped water supply in rural households

Mirzapur district, where Lahuria Deh is located, has very poor coverage of piped water supply. As per the official data of the central government’s Jal Jeevan Mission – Har Ghar Jal, as on May 11, 2022, less than 10 per cent (9.74 per cent) rural households in the district have piped water connections. Of the total 348,498 households, 33,949 have been connected with piped water supply.

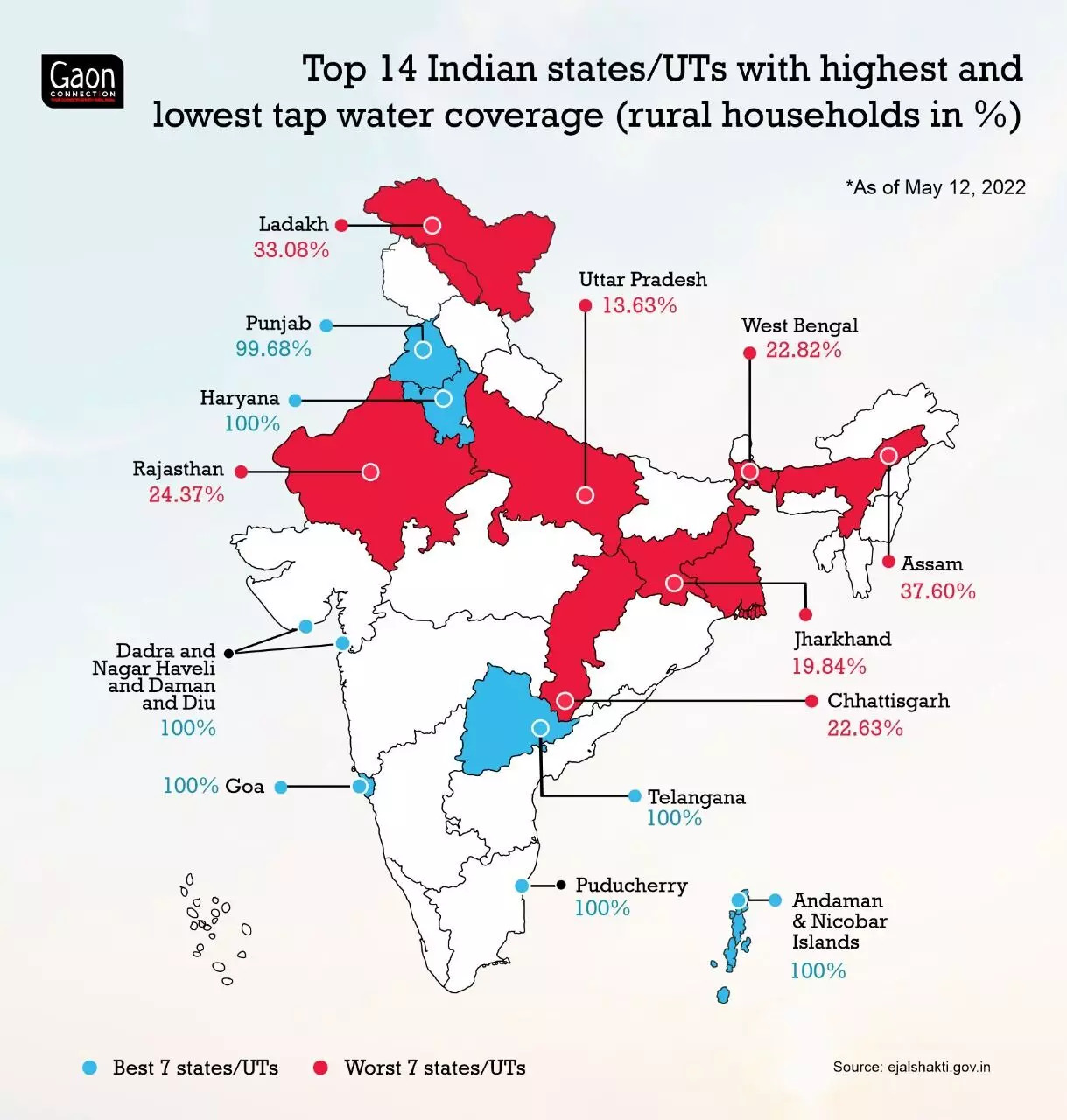

Overall, piped water coverage of rural households in Uttar Pradesh is 13.62 per cent, which is the lowest in the country. At national level, almost half of the rural households (49.27 per cent) have piped water connections.

The recurring heatwaves are adding to the suffering of the residents of Lahuria Deh. Sangam Lal, a resident of the village, was visibly agitated as he said they were living in inhuman conditions.

“Barely fifteen litres for drinking, washing, bathing, defecation and cooking in this blistering summer? Bathing is a luxury here. We bathe once every three days,” Lal complained.

Their misery is compounded if there are visitors. “Whenever there’s a family function like a wedding, we have to buy a tanker of water which costs us a thousand rupees,” Hari Lal, another resident of the village told Gaon Connection.

The cattle in the village suffered even more and were on the verge of dying, said Vinod Kumar Yadav, a cattle rearer.

“A buffalo or a cow needs a lot of water to survive, especially in summers. I am praying for their lives, my livelihood is dependent on them. I take them every day to a small jharna which is about two kilometres downhill, but that’s just not enough,” Yadav told Gaon Connection.

The National Dairy Development Board, recommends 75 to 80 litres of water a day for an adult healthy animal. But each resident of Lahuria Deh receives only 15 litres a day.

Savita, a middle-aged resident of the village said that it was the women who often sacrificed water for ensuring the smooth functioning of their households, and things had come to such a head that no one wanted their daughters to marry into the village.

“We women have to cook food from our share of the water and often sacrifice our needs in order to cater to the children and the male members. It’s been eighteen years since I came to this village after my marriage. And things have just got worse over the years,” she said.

Providing drinking water supply in Vindhyachal region

The southern region of Uttar Pradesh covering Bundelkhand and the Vindhyachal is known for water shortage. Mirzapur district falls in the Vindhyachal region.

Ashish Latare, professor at the Banaras Hindu University’s Mirzapur campus who teaches an academic programme titled Soil and Water Conservation, told Gaon Connection that the topography of this region was particularly challenging. “It is difficult to extract water from the ground and supply it to villages as the water level is too low,” Latare pointed out.

According to a press statement issued by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), Prime Minister Narendra Modi had laid the foundation stone of rural drinking water supply projects in Mirzapur and Sonbhadra districts of Vindhyachal on November 22, 2020.

“The projects, for which the foundation stones were laid by the Prime Minister today will provide household tap water connections in all rural households of 2,995 villages and will benefit about 42 lakh population of these districts. Village Water and Sanitation Committees/ Paani Samiti have been constituted in all these villages, that will shoulder the responsibility of operation and maintenance. The estimated cost of the projects is Rs 5,555.38 Crore. The projects are planned to be completed in 24 months,” the statement said.

The southern region of Uttar Pradesh covering Bundelkhand and the Vindhyachal is known for water shortage.

Almost a year later, a press statement issued by the Union Ministry of Jal Shakti on November 12, 2021, revealed that about 50 per cent progress had been made in the project that the prime minister had inaugurated. The statement also acknowledged that Mirzapur and Sonbhadra districts were situated in a water-stressed region.

“These projects will benefit about 18.88 lakh (1.88 million) households in 6,742 villages of the region,” read the statement.

Meanwhile, state chief minister Yogi Adityanath who participated in the event on November 22, 2020, in which the foundation stone was laid for water supply projects in Mirzapur and Sonbhadra had said: “In 70 years, drinking water supply projects could be regulated only in 398 villages in the Vindhya region. Today, we are here to take forward such projects in over 3,000 villages of the region.”

Meanwhile, Latare suggested that rainwater harvesting and construction of ponds and check dams can mitigate the water problem in Lahuria Deh. “Once the ponds and check dams were filled, they would replenish the groundwater, only after which water could be extracted and supplied to the hilly terrain,” he said. “It’s a gradual process but the only long term solution to the crisis,” he pointed out.