Sundarbans (South 24 Parganas), West Bengal

The succulent and juicy tiger prawns are an expensive delicacy in fine dine restaurants in cities.

But that price often hides the real price women like Chandna Mondol pay. She and others like her spend hours standing waist-deep in brackish water collecting bagda or the prawn seedlings, and suffer a number of diseases including skin infections and reproductive disorders.

These women are known as meendhara or prawn seedling collectors, who sell these seedlings to middlemen who cultivate the prawns.

“Noon jal theke hoye [It happened because of salt water],” Chandna told Gaon Connection as she peeled discoloured skin off her palms.

The 47-year old has eczema — a condition in which the skin becomes inflamed, itchy, cracked, and rough.

Since her marriage at the age of 13, Chandna has been spending several hours every day standing in the brackish water of Bidyadhari river near her village Sonagar in the Indian Sundarbans region, which is the top producer of tiger shrimps in India.

The poorest of the poor women of the Sundarbans in West Bengal, a tidal region at the confluence of Ganga, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers in the Bay of Bengal, eke out a living by collecting prawn seedlings. It is estimated that collecting prawn seedlings from rivers is an important livelihood source for more than a lakh of poor women on the estuarine delta of the Sundarbans.

After backbreaking work, these women sell their catch for Rs 200 for 1,000 seedlings to the local middlemen who cultivate prawns in bheries or large artificial enclosures in Canning and other parts of South 24 Parganas district.

The bagda is cultivated for over three months in these bheries, post which the adult prawns are sold in wholesale markets and then moved to the export market.

West Bengal is the highest producer of tiger shrimp in India producing 50,000 tonnes from an area of 51,000 hectares. But, this comes at a cost for the meendharas who suffer physical and mental health problems on account of the work they do.

“My palm keeps itching. I also feel the itch in my legs, stomach and back. I rush home to bathe and change from my wet saree that sticks to my body all day long,” she said, adding that she has been spending Rs 500 every month for treatment. A large chunk from her monthly income of nothing more than Rs 2,000.

“My husband migrates to Andhra Pradesh for a few months every year. But we don’t depend on his money for our survival. It is the money from this meen [fish] which feeds us,” she told Gaon Connection.

Yadhoda Mondol(left), Devika Burman(centre), Chandna Mondol(right): the women across three generations have been prawn seedling catchers

The nearest hospital to Chandna’s village is Gosaba rural hospital, seven kilometres away as the crow flies, but it takes over an hour to reach there by ferry.

“Urinary Tract Infections are very common in women living in poor sanitary conditions, and they are further aggravated by the salty water they stand in,” said Sagarika Sardar, general duty medical officer at the rural hospital.

There are other medical complications too. “These women (meendharas) stand hip deep in the brackish water and often suffer from fungal infections in their toes, nails, and in between the thighs,” Dr Indranil Saha, Senior Consultant, Gynecology and Obstetrics in Kolkata, told Gaon Connection.

Like her mother, Chandna’s 33-year-old daughter Devika Burman is also a meendhara. She has been on this job since she was 10 years old.

“I do not miss even a day of work, even when I have periods. Missing even one day means losing a day’s wages,” said Devika. “The salt water causes jalan (burning) and pain. I see the village doctor (quack) every month to get medicines. But it doesn’t get treated completely, and the infection returns again and again,” she added.

Painkillers help these women cope with the drudgery of their work. “I take a painkiller almost every day. That is the only way to survive catching meen. The doctor in my village gives me something that relieves joint pain, but then after a while it comes back and I have to pop another pill,” said Devika.

According to Dr Indranil Saha, standing in brackish water and fishing for a long time can lead to vaginal infection. “In the absence of proper healthcare, these women take random antibiotics or antifungals from quacks and become resistant to it.”

“In this condition if they have intercourse, there is a chance to contract a sexually-transmitted disease too. The recurrent infections can sometimes result in infertility,” he added.

The health cost of Sundarbans’ tiger prawns

A 2022 survey titled The perils of prawn-catching for women in Sundarbans found out that of the 994 sampled households from 50 localities spread across the delta, 252 were involved in catching prawn seedlings and that the meendharas had significantly more health problems than their counterparts who engage in other low-wage activities.

These health problems are clustered in a subset of the 67 ailments enumerated by the survey: irregular menstruation, problems with eyesight, gastric pain, pain in the hands, legs and knees, skin allergies and itching.

The 2022 study goes on to note that prawn seedling collection is the only income earning opportunity these women have, because of their “spatial immobility and low education levels”.

West Bengal is the highest producer of tiger shrimp in India which comes at a cost for the meendharas who suffer physical and mental health problems on account of the work they do.

Since her marriage at the age of 13, Chandna has been spending several hours every day standing in the brackish water of Bidyadhari river near her village Sonagar in the Indian Sundarbans region.

A two-hour ferry ride away from Chandna’s Sonagar village is Bali island. Kumala Sarkar, who lives in Bali II gram panchayat, lost her friend to a tiger attack while fishing from narrow canals in deep mangrove forests of the Sundabans in 2007. But she has continued to be a meendhara.

“My inner thighs had terrible itching after I started with bagda catching. Standing in water wasn’t easy either. I saw that my skin started drying up and peeling,” said the 66-year-old.

But that wasn’t the worst. Over time Kumala found her eyesight growing weak and this reduced her ability to spot the fine brown hair-like seedlings in the muddy waters.

“My eyes watered and became painful. Finally I had to stop catching them,” Kumala told Gaon Connection.

Also Read: Who moved my village?

When Kumala had started out, she could get Re 1 per bagda but as the demand dwindled so did the price. Rs 200 per 1,000 seedlings now is not even bare minimum for her. It’s been over five years since she exited the profession. About her eyes — she neither wears spectacles nor has any financial ability to get them treated.

Poor healthcare infrastructure

Neither Bali II, nor Sonagar village has a fully functional hospital which can cater to the health needs of the women like Kumala, Chandna and Devika.

The Gosaba rural hospital with its five doctors caters to the population of nine islands under the block, which sees a footfall of 150 to 180 patients daily. The hospital however has no diagnostic facility to even confirm a Urinary Tract Infection.

“The vaginal infections might be common in fisherwomen due to their continuous exposure to salt water. This is the only hospital for the inhabitants of all the nearby islands. As I recall, there have been five cases of cervical cancer which were then referred to Canning,” said Sumit Khan, general duty medical officer in Gosaba rural hospital.

The Gosaba rural hospital with its five doctors caters to the population of nine islands under the block, which sees a footfall of 150 to 180 patients daily.

On Bali island, a rural hospital was opened in 2022 but it’s barely visited by the people. “We don’t go to that hospital. The doctors are hardly there. It is only helpful in case of certain vaccinations and medicines for fever,” said Yashoda Dar, a resident of Bali II.

But to offer some respite is a non-profit healthcare facility under the purview of Sundarban Foundation, run by Prasanjit Mandal. The hospital was opened in 2016 in Bali island.

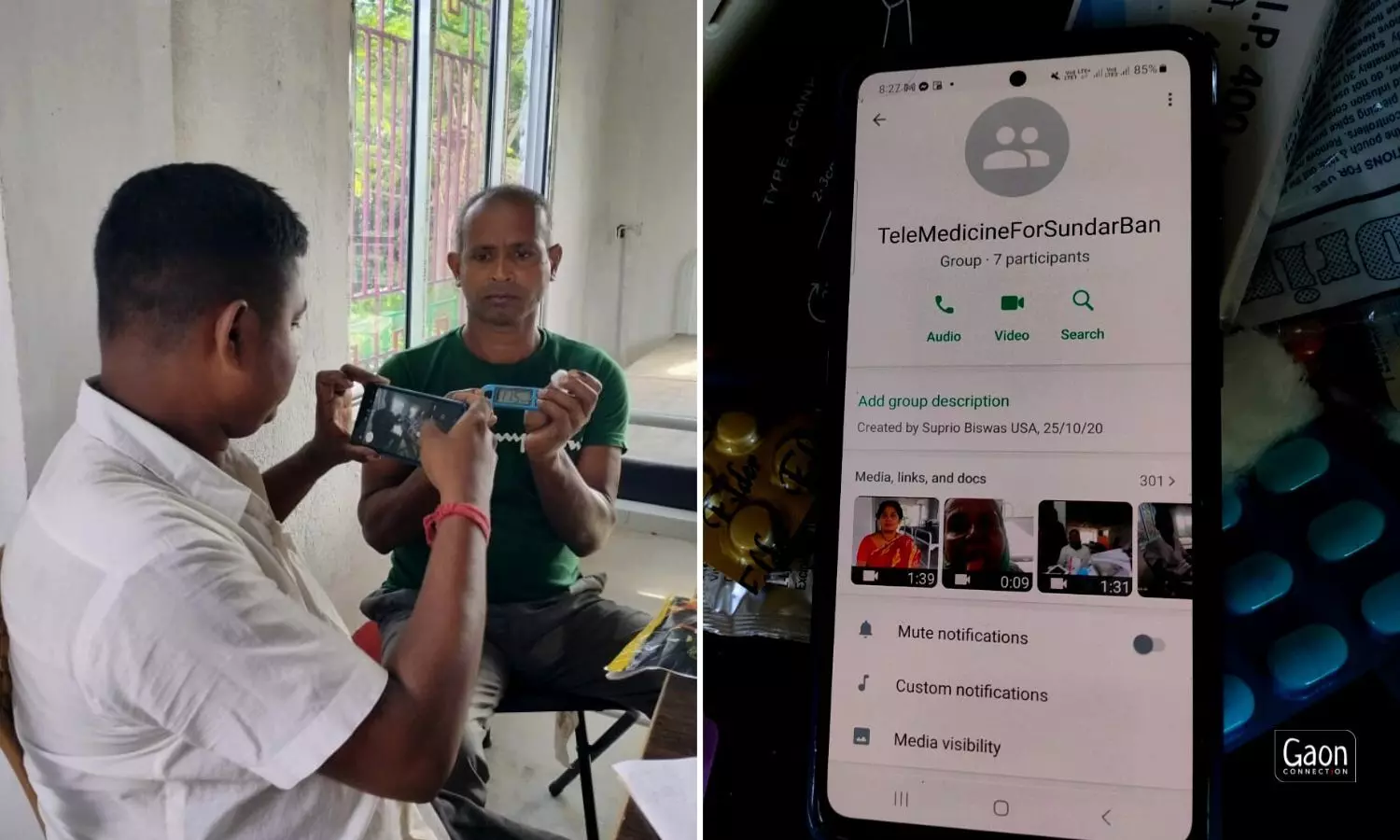

He has created a network of qualified doctors for telemedicine aid to the villagers in the islands of the Sundarbans.

A non-profit healthcare facility under the purview of Sundarban Foundation, run by Prasanjit Mandal has created a network of qualified doctors for telemedicine aid to the villagers in the islands of the Sundarbans.

“I make a video of the patients explaining their symptoms and share it on the WhatsApp group I have created with these doctors. The concerned doctor takes a look at the patient and suggests the treatment. Unless something is serious, we are able to handle it at our facility,” Prasanjit told Gaon Connection.

But, many of the poor meendharas neither have time nor smartphones for virtual consultations.

This is the second part of a two-part series. You can read the first part here. The article is written under the Laadli Media Fellowship, 2023. All the opinions and views expressed are those of the author. Laadli and UNFPA do not necessarily endorse the views.