Supaul, Bihar

Ever since the Bihar government announced in September, 2020 that it will conduct an extensive land survey, 50-year-old Bahadur Sada has been living in anxiety in his Bauraha gram panchayat (village council) in Supaul district. The surveying of the land, which is supposed to conclude by 2023, is expected to establish the formal ownership of the lands in the state.

Sada’s anxiety stems from the flow of the Kosi river, which is historically known to change its course in almost every rainy season. Such shifting of its course often brings devastating floods, which is why Kosi is often termed as the ‘Sorrow of Bihar’.

The changing course of Kosi also engulfs lands and leads to land disputes – does the land belong to the river, the government, or the local villagers? Such disputes around Kosi’s flow often erupt in the districts of Saharsa, Purnea, Khagaria, Madhubani, Sitamarhi, Muzaffarpur, Darbhanga, and Supaul, which witness the annual inundation of thousands of hectares of farm lands and the displacement of millions of rural inhabitants.

The state government claims the land survey will put such disputes to rest, but the villagers, such as Bahadur Sada, who live along the banks of Kosi are a worried lot. They are protesting against the rules of the survey as per which any land that is submerged by the river will be surveyed as the government land.

Bahadur Sada

“I have been living in this village for many generations. My ancestors owned upto 15 bighas (almost four hectares) of land and now I am only left with three bighas. The Kosi nadi (river) consumed my land,” Sada, a resident of Bauraha village in Supaul district, told Gaon Connection. “I have paid taxes on my land. I was expecting compensation from the government for the losses over the years but it seems they are about to take over the remaining land as well!” the worried farmer added.

Also Read: Pandemic, poverty, recurring floods and human bondage in Bihar

“The problem is that after the changes in the river’s course, it is difficult to ascertain where exactly my land is located. I wonder what the surveying officials will do now… I fear I’ll lose all my land,” said the 50-year-old who is amongst the thousands of farmers protesting against the survey.

Hariram Yadav, a 76-year-old resident of Sonarbasa village in Madhubani district, echoed Sada’s concerns. “As per the rules of the survey, the two bighas of my agricultural land will automatically be taken over by the government. My family depends on it for survival. I have been paying taxes all these years in the hope that I will someday be allowed to own the land formally,” the farmer said. He said that he was the only one amongst his four brothers still staying in the village. “Rest all three have migrated elsewhere in search of livelihoods,” he said.

Hariram Yadav

Keeping in mind the angst of the local villagers, the land survey between the embankments of the Kosi has been suspended for now, informed a government official.

“The protesting farmers are demanding that such tracts of land should be formally allotted to them. I have requested my department to direct us about the course of action that should be taken. For now, we have suspended the land survey in the embankment areas of the Kosi river,” Bharat Bhushan Prasad, a Supaul-based settlement officer from the Revenue and Land Reforms Department, who’s part of the surveying exercise, told Gaon Connection.

All the survey work on the disputed land between the embankments of Kosi has been suspended in the wake of protests. These protests are most intense in Supaul district.

The ‘controversial’ rules of the land survey

A comprehensive state-level survey of land for revenue purposes was last conducted in 1911 during British rule.

“For instance, Patna district has completed Cadastral Survey in 1911 and till now revisional survey has not completed, so far. So all the land revenue works are going on the basis of the records of cadastal [sic] survey of 1911,” stated a research paper titled Assessment of Land Governance in Bihar published in ResearchGate journal in April, 2015.

The land survey, which the state government announced in September 2020 and whose work is currently underway, is in the eye of the storm.

Bharat Bhushan Prasad, the Supaul-based settlement officer, told Gaon Connection that as per the rules of The Bihar Special Survey and Settlement Act, 2011, the land along the flow of the river and between the embankments belongs to the state government.

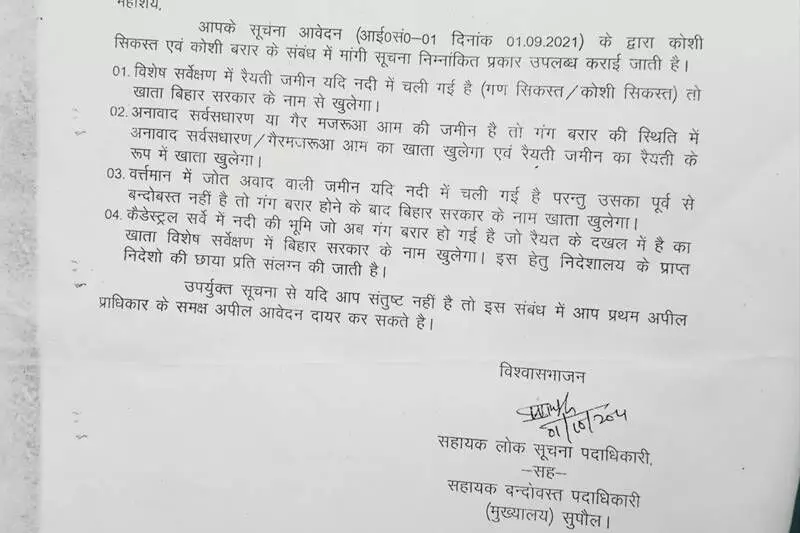

Further, on April 4, 2021, while replying to a Right to Information (RTI) petition, the Assistant Settlement Officer of Supaul, had explained the rules of land settlement.

The official stated in the reply to the RTI that if the river is flowing through farmland, the land in question will be legally in possession of the state government. In addition, he also stated that those tracts of land which were submerged by the river in the cadastral survey but were later modified into farmland also belong to the government.

As per the RTI reply, following are the rules of conducting the survey of land along the flow of the rivers in the state:

* Any cultivable land that has submerged within the river will be surveyed as government land.

* Any non-cultivable land that surfaces from the river after the water recedes will be counted as community land without the proprietorship of any individual.

* If any disputed land is submerged by the river then it will be taken over by the government after the river waters recede.

* The cultivable land which has been surveyed before in the last cadastral survey will be surveyed as government land.

While replying to a Right to Information (RTI) petition, the Assistant Settlement Officer of Supaul, had explained the rules of land settlement.

These survey rules have become a bone of contention leading to suspension of the land survey between the embankments of the Kosi.

Administration and farmers at odds

Mahendra Yadav, president of the Kosi Navnirman Manch — an organisation protesting against the survey — told Gaon Connection that the entire attempt to survey the land along the river is ambiguous as the river keeps changing its course.

“The river doesn’t flow as per the maps followed by the government. It has always changed course and will continue to do so. There are many villages where only one-third or two-third of the agricultural land would remain if the government follows the survey rules,” Yadav told Gaon Connection.

“If the government wants to take over the land, it should draft a rule under which farmers would own the land if the river changes its course in future,” he added.

The protesting organisation’s leader also said that the protests would continue unless the government accepts the farmers’ demands.

Also Read: Uttarakhand: Lohari village goes under water, displaced villagers demand land for resettlement

The curious case of Kosi river

Having worked on the construction of the Kosi Barrage in the past, Amod Kumar Jha, an engineer from the state government’s Road Construction Department told Gaon Connection that Kosi river is perhaps the most unpredictable river in the world.

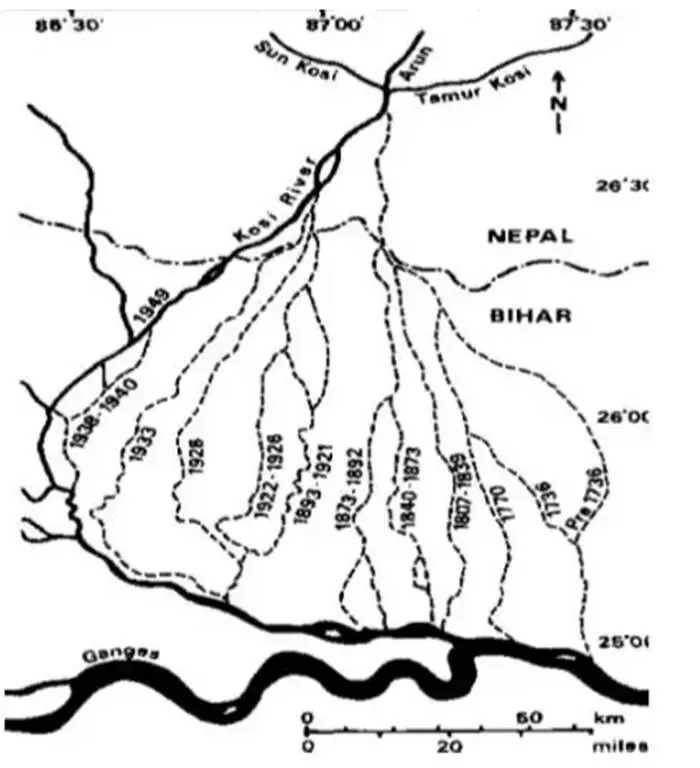

“Kosi, which is a tributary of the Ganga river, shifts its course by great distances. In 1731, the river used to flow near Forbesganj and Poornia, then in 1892, it began flowing from Murliganj, in 1922, it flowed from Madhepura while in 1936, it began flowing from Saharsa and Darbhanga. Likewise, it has drifted about 110 kilometres in almost 200 years,” Jha said.

Photo credit: Water Resources Department Bihar

Also, the Water Resources Information System — a database prepared by the Union government, the Kosi is well known for its tendency to change its course generally in westward direction.

“During the last 200 years, the river has shifted westwards for a distance of about 112 km and has laid waste large tracts of agricultural land in Darbhanga, Saharsa and Purnea districts. The total catchments area upto its outfall in the River Ganga is 100800 sq.km [square kilometres],” the database mentions.

In such a scenario when the river keeps changing its course, submering new lands, who does the land belong to – this is a question for which there are going to be no easy answers.