Aali village (New Delhi) and Gurugram (Haryana)

Krishna is worried about her three grandchildren. “It has been three months since the anganwadi centres have been shut. The children would get dry ration from the anganwadi centre nearby but nothing now. The anganwadi workers taught the children too but everything has come to a halt since December,” the 65-year-old resident of Ashok Vihar in Gurugram, Haryana, told Gaon Connection.

Her grandchildren – Pratibha, Komal and Ansh – ages ranging between one-and-a-half-year and four-and-a-half-year now, spend all their time at home doing nothing. There is no money to send them to private schools. Worse, with no dry rations coming in, it has become difficult to feed them as well, she worried.

Across the state border, about 40 kilometres away, the residents of Aali village in the national capital New Delhi had similar woes where the anganwadi centres are shut for a month now.

“When the anganwadis were open, we got some rations like gud (jaggery), chana and dalia. Now, that has stopped and our expenses have increased,” lamented Samesh Devi, a 25 year old resident of Aali village in south Delhi. Her four years old child is enrolled at the local anganwadi (government-run early childcare centre)

Anganwadi centres in Delhi and Haryana are closed as the anganwadi workers are striking work, asking the government to address their long pending demands including raising of their honorariums. While anganwadi workers and helpers in Haryana have been protesting since December 8, 2021; in Delhi, the protests began on January 31, 2022 and continue even now.

The government and the protesting workers have failed to find a middle ground, and it is the anganwadi beneficiaries – the under-6 children – who are at the receiving end as dry ration distribution through these centres has taken a hit. These anganwadi centres had opened briefly after remaining shut through the pandemic, but are closed once again due to the ongoing indefinite strike.

Last week, on February 24, the Delhi government announced increasing the monthly payment of anganwadi workers to Rs 12,720 and that of the helpers to Rs 6,810 per month. However, the protesting workers are not ready to accept the offer.

GOOD NEWS FOR DELHI’S ANGANWADI WORKERS!

➡️Kejriwal Govt increases their pay to ₹ 12720 / month

➡️This is the HIGHEST in India

➡️Helpers will now get ₹ 6810 / month

➡️Last week we had met their union & have increased it before the promised time

-Shri @AdvRajendraPal pic.twitter.com/7BzaZLGRFX

— AAP (@AamAadmiParty) February 24, 2022

“With the proposed increment Delhi’s honorarium for Anganwadi workers would be Rs 12,700 for workers and Rs 6,810 for helpers. This includes the communication allowance of Rs 1,500 per month for workers. However, the Anganwadi workers in Delhi have not been getting the communication allowance for the past 2 years! Thus, the real honorarium after the recently proposed increment is only Rs. 11,200,” said Shivani Kaul, president of the Delhi State Anganwadi Workers and Helpers Union, the union leading the ongoing strike of anganwadi workers and helpers in Delhi.

Why are anganwadi workers on an indefinite strike?

Since 2018, anganwadi workers have been demanding that the government make good on the promise made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to raise their honorarium. In Haryana, the demand has been for an increase in the monthly honorarium of the workers and helpers by Rs 1,500 and Rs 750 respectively.

These women frontline workers, who are not treated as an ’employee’, have also been demanding other allowances such as dearness allowances, retirement benefits, regulations of services, etc. Currently, the anganwadi workers and helpers in Haryana are paid Rs 11,811 and Rs 6,045 as monthly honorariums, respectively.

On the other hand, anganwadi workers and helpers in Delhi who are earning Rs 9,678 and Rs 4,839 respectively, are demanding that their honorariums be increased to Rs 25,000 and Rs 20,000 per month.

“Close to 52,000 anganwadi workers and helpers have been on strike for three months,” said Babita, an anganwadi worker from Gurugram in Haryana. “Every time we protest, the government says that it will implement them [our demands] after we call off our protest. This time,we won’t budge unless we get it in writing that our honorariums will be increased from immediate effect,” she told Gaon Connection.

On the closure of anganwadis for three months, and the effect it has had on children, Bharatiya Janata Party’s Haryana spokesperson, Raman Malik said, “This is a service, a service for which there is no salary but an honorarium. You can’t hold children to ransom, that’s wrong. So, our request to the anganwadi workers would be to not hold children to ransom, this is an honorarium given.”

The party spokesperson went on to add: “If I am not wrong Haryana is number two, in India, in the quantum of honorarium given to anganwadi workers… An anganwadi worker is not someone who is too skilled but still they’re getting Rs 12,000-13,000 a month which is not bad.”

Child nutrition suffers

The anganwadi workers and helpers are a part of the Indian government’s Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) for early childhood care and development, which is the world’s largest such programme. The beneficiaries include children between the age of 0-6 years, pregnant women and lactating mothers.

The anganwadi workers provide supplementary nutrition, pre-school non-formal education, nutrition and health education, immunisation, health check-up and referral services. For their duties during the COVID-19 pandemic, they were declared frontline workers by the government. Despite the anganwadis being shut during the pandemic, these workers and helpers distributed dry ration to all the beneficiaries, often by foot.

However, according to Babita, there was no real acknowledgement of the enormous work the anganwadi workers put in during the pandemic. “The government didn’t even provide us with masks and sanitisers. We made masks at home for ourselves and others. We imparted information about the correct COVID-19 protocol to be followed and conducted surveys in villages to provide information to the government. The government is now denying and nullifying the work that we did for its own gains,” she said.

While families of beneficiaries understand the troubles anganwadi workers and helpers have taken to supply dry rations during the pandemic, they are worried that the indefinite strike has led to a stop to such rations.

For Sheela, a resident of Ashok Vihar in Gurugram, the anganwadi was a lifesaver. Her daughter, Shelly, who is now 1.5 years old, weighed less than four kilograms (kg) when she was seven months old. “Had it not been for anganwadi didi, my daughter might not have recovered so soon. Didi gave me tips about the nutrition my daughter needed and the ration she gave me helped Shelly recover,” the 28-year-old mother told Gaon Connection.

But, now there is anxiety all over again as household expenditure has increased and there has been no rations coming in. “We haven’t received any ration since December. Uski wajah se ghar ka kharcha badh gaya hai [household expenditure has increased],” said Sheela, who informed that the children were entitled to milk powder, refined oil, dalia and chana from the anganwadis.

“Initially, when the cases were high, the anganwadi workers would deliver the dry ration packets to our homes,” she said. The anganwadi centres provided take-home ration to the children twice a month. The workers would also ensure delivery of dry ration to the homes of women who didn’t have mobile phones.

Krishna, the grandmother of three, had similar complaints. “Private schools are expensive for us, and now the anganwadis are shut. While we received dry rations from anganwadis during lockdown, now we don’t.”

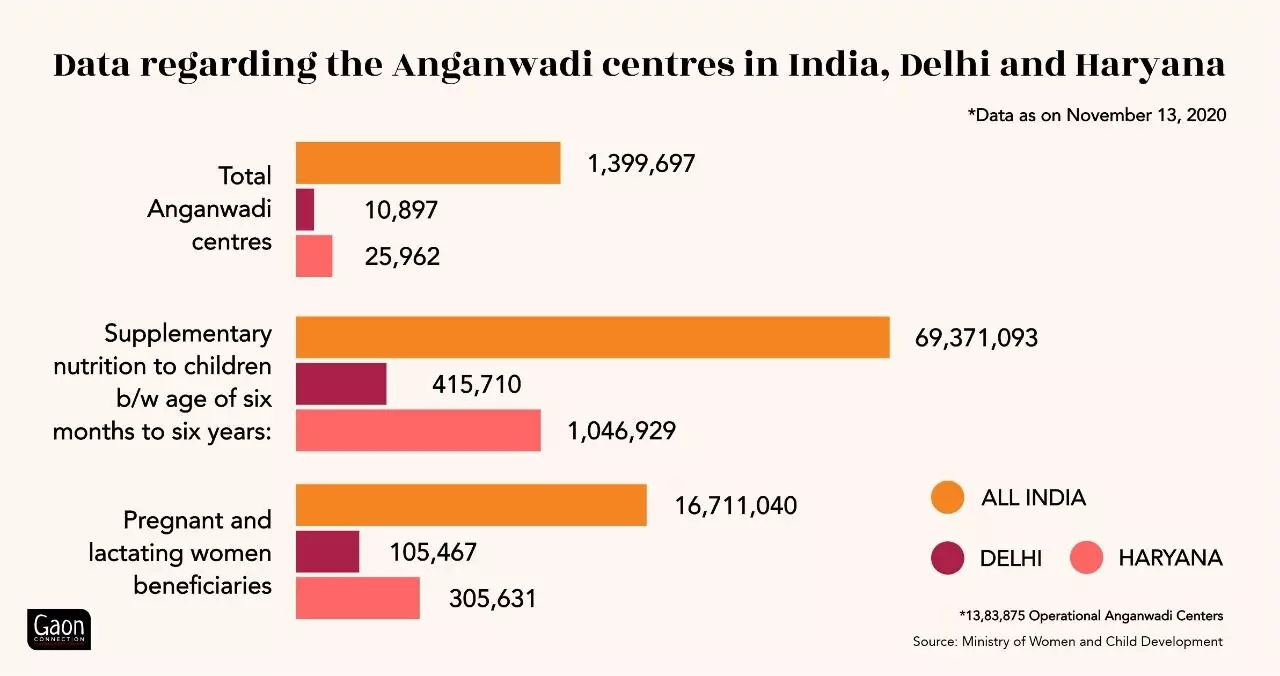

There are 1,320,708 anganwadi workers in India out of which 9,353 workers are in Delhi and 25,152 workers in Haryana. On the other hand, there are 1,182,263 anganwadi helpers across the country out of which Delhi has 10,738 and Haryana 24,485 helpers.

All these millions of beneficiaries have been affected due to the ongoing indefinite strike in Delhi and Haryana.

Anganwadis shut amid rising food insecurity

About eight in 10 surveyed households (79 per cent) have reported some form of food insecurity during the pandemic and an alarmingly high 25 per cent reported severe food insecurity. These are the survey findings of Hunger Watch – II conducted by the Right to Food Campaign and the Centre for Equity Studies between December 21 and January 2022. It was recently released on February 23.

Apart from provision of dry ration, the anganwadi centres also acted like creches for under-6 children and provided early learning.

Samesh Devi, a resident of Delhi’s Aali village told Gaon Connection that sending her four-year-old son to the anganwadi was very convenient for her. “I was free to attend to my household chores, and once I was done, I would go and pick him up,” she said.

Samesh Devi is also struggling to make ends meet since the anganwadis shut down. “I am forced to pay Rs 200 a month for private tuition for my child. It is money I can ill afford, but I have no options,” she said.

Anjana Sirkar, another resident of Aali village, said that anganwadi acted as a bridge to regular schools. She was worried about her three-year-old daughter Isra. “It is difficult for children to adjust straight away in the schools. Anganwadi centres worked like a play school – the children learn how to sit in these schools, draw, count numbers, read alphabets. Now, the kids have nothing to do,” she said.

On February 4, 2022, opposition leader Rahul Gandhi, Congress supremo, posed a question in the Lok Sabha to Smriti Irani, the Minister of Women and Child Development, about the long term impact of closure of anganwadi centres on early childhood care and education and malnutrition.

दिल्ली सरकार जनता के दर्द नहीं समझती। आंगनवाड़ी कार्यकर्ताओं के हक़ की लड़ाई एकदम सही है।

कोविड में अपनी जान की परवाह ना करते हुए इन्होंने जन सेवा की।लेकिन दिल्ली के CM ना तो उन्हें पर्याप्त वेतन दे रहे हैं, ना समय, ना सम्मान।

नाम के आम आदमी!

— Rahul Gandhi (@RahulGandhi) February 16, 2022

In response, Irani said, “Anganwadi Centres are closed due to Covid-19 pandemic. No impact study/survey (to study the impact of pandemic on nutritional status of women and children and on Early Childhood Care and Education) has been planned on ground, as human interaction has been minimised to control the spread of virus.”

Child nutrition may suffer

“If you starve a child of its nutrition, for a length of time, it will lead to a generation of stunted children,” warned Veena Shatrugna, former deputy director, National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad.

“The child will stop putting on weight, stop growing in height – that’s the first thing that happens to children,” she said.

Emphasising how anganwadi was a place where kids interacted with each other, Shatrugna stated: “There are many studies from South America which confirm that stimulation improves the child’s nutritional status. When a child is left alone at home, all that disappears.” Anganwadis were meant to be like creches providing safety, security and stimulation.. with a little bit of teaching, learning. All that has gone, the former deputy director pointed out.

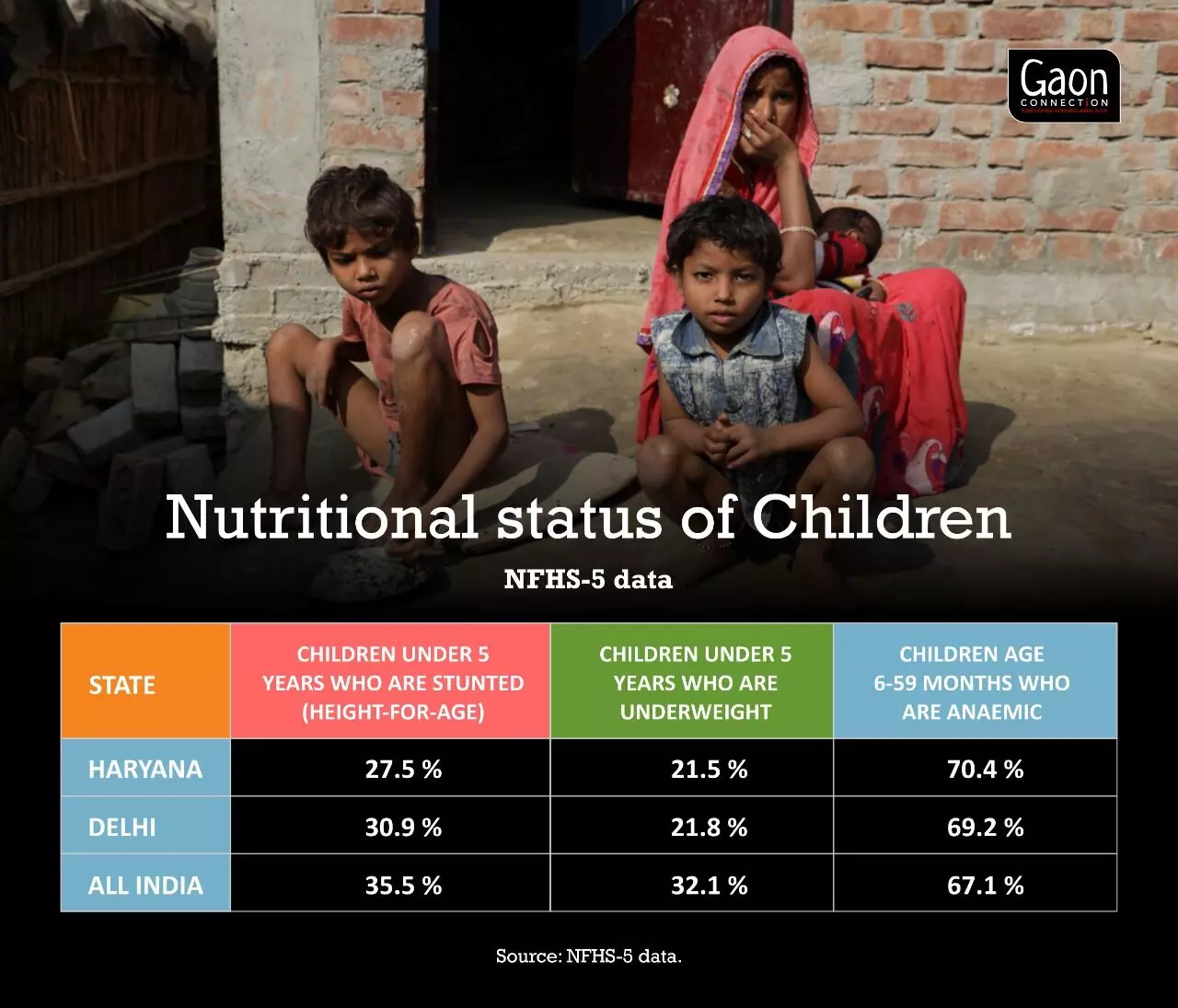

The public health experts also warn of a rise in child health issues. “This generation of children is going to show severe nutrition issues and that’s what NFHS-5 [National Family Health Survey] is also showing with respect to anaemia. The comprehensive nutrition survey [2016-18] is also showing nutrition deficiencies,” Sylvia Karpagam, Bengaluru-based public health expert, told Gaon Connection.

As per the health ministry’s NFHS-5 data released last year, in Haryana, children under five years who were stunted stood at 27.5 per cent. In Delhi it was 30.9 per cent whereas the all India figure was 35.5 per cent.

Children under five years of age who were underweight in Haryana stood at 21.5 per cent, in Delhi it was 21.8 per cent while the all India figure stood at 32.1 per cent.

In Haryana, a worrying 70.4 per cent of children in the age of six to 59 months were anaemic; in Delhi it was 69.2 per cent, and the all India figure stood at 67.1 per cent.

“We are expecting a resurgence of more severe forms of nutrition deficiencies like rickets, night blindness, aggravation of stunting in underweight children, because of which they are more likely to fall sick as they are vulnerable to diseases,” Karpagam warned.

Anganwadi workers say they are suffering too

On February 22 and 24, Gaon Connection visited some anganwadis in Gurugram, Haryana, and south Delhi and found these centres shut. The anganwadis in Ashok Vihar Gurgaon, Haryana were locked. One of them was a rented premise located over a temple, while the second anganwadi centre was a small room in someone’s home.

A local resident, whose twin children once received rations from the anganwadi, told Gaon Connection on condition of anonymity that the family had received no rations in the past three months.

An anganwadi worker who didn’t wish to be named said how parents keep enquiring when the centre will open. “I have told them that as soon as Khattar [chief minister of Haryana] accepts our demands, we will go back to the centres,” she said.

For many of these women workers, the anganwadi honorarium is their only source of income. “I have not earned a paisa for the past three months. I am a widow and have two children who are studying. I earned Rs 10,000 a month for my work at the anganwadi, and it’s difficult to run a family with so little,” Sudhesh Phogat, an anganwadi worker, told Gaon Connection. “We have been on roads, protesting, since December 8. I have to manage by asking others for money,” she added.

Apart from their charter or duties, the anganwadi workers say they have to do extra work for the government. “We have to prepare reports at night, and we are not paid for that. There’s no respect for our time at all,” said Phogat.

The children have already suffered enough in the past two years of the pandemic. And it is high time the government helps end the impasse and ensures that the anganwadi beneficiaries receive their rightful rations.