Sitapur/Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh

At around 4 pm on June 15 last week, 22-year-old Jaydayal Yadav left home to irrigate the bajra (pearl millet) crop on his half a hectare land in Bangarha village, along with a few members of his family. Little did he know then that he would not return alive. The 22-year-old was shot dead.

“There was a feud over who would irrigate the field first, and that led to the killing of my brother,” Amit Yadav, Jaydayal’s 20-year-old brother, who was with him at the time of the shooting, told Gaon Connection.

“The pipe [for irrigation] was spread over the field and we were ready to water the crop. But, just then another group of farmers started to quarrel as they wanted to irrigate their sugarcane crop first. One of them brought a bandook (gun) and shot my brother. He died instantly,” Amit recounted.

“We had brought our own engine (a diesel-operated water pump to extract groundwater) from the tubewell… the conflict was over who would use the tubewell water first,” Amit, who along with two other relatives also sustained injuries during the clash, said.

Also Read: A Midsummer Pipe Dream: Pipelines laid down and taps installed, but where is the water?

Something similar unfolded the following day, about 100 kilometres away from Sitapur. In the neighbouring district of Barabanki, violent clashes over water left four farmers injured and one of them is battling for his life at a government hospital in the state capital, Lucknow.

“Ashish Yadav was shot at in a clash over the issue of irrigating fields while another person who was a bystander was injured too. At least six individuals have been detained in this case,” Dinesh Kumar Dubey, the circle officer of Ramnagar of the Uttar Pradesh Police told the press on June 16.

As per sources in the Irrigation and Water Resources Department, as much as Rs 25 million is annually spent on the repair, maintenance and desilting of the canal network in Sitapur district alone.

Conflicts over water in rural India are commonplace but gun battles over irrigation water shows the growing and worrisome nature of the crisis.

With the early arrival of heatwaves in the country, farmers in Uttar Pradesh are still waiting for the monsoon that is yet to arrive. Crops such as sugarcane and mentha (peppermint) are wilting due to lack of water.

Almost 78 per cent of irrigation needs in the state are met by groundwater sources like tubewells and dug wells, notes the Ground Water Year Book Uttar Pradesh 2018-2019. But, due to over-dependence on groundwater, water tables in several districts of the state are dipping fast, which is adding fuel to the distress of farmers.

Frequent power cuts and skyrocketing prices of diesel are adding to their misery.

“The way we are irrigating fields with groundwater is absolutely unsustainable. The groundwater reserves are not infinite and it will pose a serious threat to us in the coming decades,” Venkatesh Dutta, Lucknow-based professor at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University, told Gaon Connection.

When canals run dry

The canal irrigation network in Uttar Pradesh measures upto 74,660 kilometres and includes rajbaha (smaller canals) and drains which help in transferring water from the main canals to the agricultural fields.

माननीय मुख्यमंत्री श्री @myogiadityanath जी के मार्गदर्शन में सिंचाई एवं जल संसाधन विभाग द्वारा 143.32 लाख हे० भूमि सिंचित की जा रही है। #JalShakti4UP pic.twitter.com/PPsTOr3m4w

— . (@UPIrrigationDep) April 6, 2022

“Canal irrigation is the cheapest form of irrigation available to farmers,” Manoj Maurya, a farmer from Bhuta block of Bareilly district, told Gaon Connection. However, this vast canal network in the state is failing to meet the irrigation needs, as either the canals are broken or they have run dry, he said.

“My agricultural fields were once irrigated by the canal which flows almost 250 metres away but for almost 15 years now, I have had to water my crops using an engine on a tubewell. This is because the small drains that brought water from the main canal have all been damaged, encroached upon or have simply worn out,” Maurya said.

Also Read: When disease and deformity are just a sip away

On June 15, when Gaon Connection visited Madhia village in Sitapur’s Maholi block farmers were struggling to irrigate their fields at midnight.

Tucked in your bed to sleep?

But sleepless farmers are spending day & night in their fields under the open sky to irrigate their sugarcane crop. Canals don’t have enough water, water pumping motors don’t work due to long power cuts. Detailed ground report soon!

: @ramji3789 pic.twitter.com/Iny0EMZ3NG

— Gaon Connection English (@GaonConnectionE) June 15, 2022

“People in the nearby villages divert the flow of water from the naala (canal’s drains) during the day so we have to wait the entire day to water our crops,” Guddu, a farmer in his twenties from Madhia village, told Gaon Connection. “We cannot afford to run the pumps as the diesel prices are hitting the roof. We have no option but to wait for the water to flow in the naala to irrigate our fields,” the farmer added.

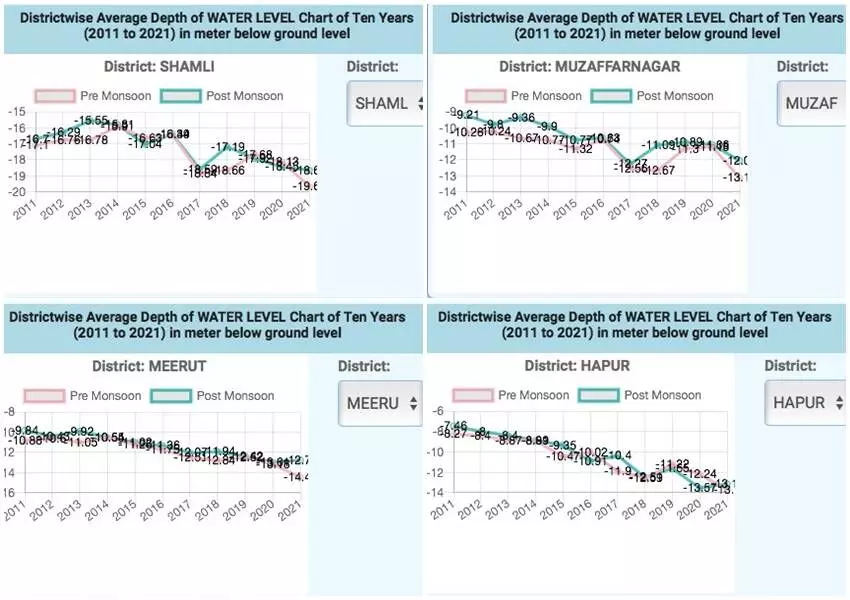

“The old drains that used to bring water from the canals to the fields are nowhere to be found. We ourselves dig these small drains and patiently wait for the water in the canal to flow. Groundwater level is also falling every year,” the worried farmer said.

Another farmer from the Madhia village that encroachment and damage to the canal’s drain by the villagers hampers the irrigating prospects of farmers like him.

“Many people in the village have damaged sections of the drain that emerges from the canal. Some have encroached on it as well,” Dheeraj Tiwari told Gaon Connection.

According to the Union Ministry of Jal Shakti, Uttar Pradesh has the longest network of rivers and canals in the country.

On being contacted, Vishal Porwal, a Sitapur-based executive engineer in the Irrigation and Water Resources Department said: “Canals are definitely the most economical and ecologically friendly method of irrigation. We expect rural inhabitants and farmers to take care of the canals and not encroach or damage them. If someone is found damaging the canals or their small drains, we take legal action against them,” Porwal said.

Maintaining the canal network is expensive. For instance, as per sources in the Irrigation and Water Resources Department, as much as Rs 25 million is annually spent on the repair, maintenance and desilting of the canal network in Sitapur district alone. And Uttar Pradesh has a total of 75 districts!

A government worker called a seenchpal is responsible for maintaining parts of the canals to ensure irrigation is not interrupted, informed an official.

“Each seenchpal looks after an eighteen kilometre stretch of canal. We are facing manpower shortages in looking after the canals at the ground level as a result of which these workers often face tough challenges,” the source, who did not wish to be identified, informed Gaon Connection.

Over-dependence on groundwater

According to the Ground Water Year Book Uttar Pradesh 2018-2019, almost 78 per cent of the irrigation in the state is met by groundwater sources like tubewells and dug wells.

But, groundwater levels are fast falling.

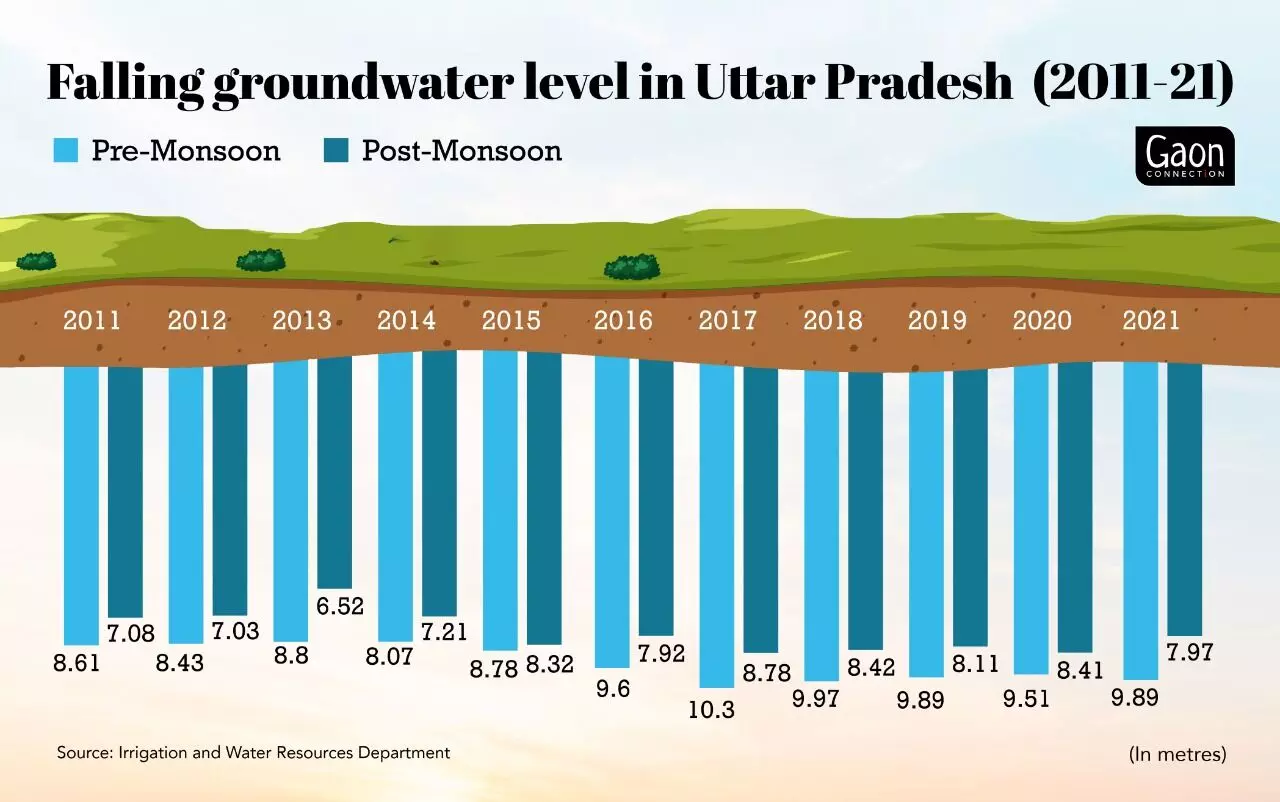

As per the official data, the groundwater level (average for the state) during the pre-monsoon season dropped from 8.6 metres in 2011 to 9.8 metres in 2021 registering an overall decline of 1.2 metres. Similarly, for the post-monsoon season, the groundwater level dipped from 7.08 metres to 7.97 metres from 2011 to 2021.

Source: https://jjmup.org/wq/gwd.php

Dipping groundwater levels means extra time and additional cost to the farmers in extracting water.

“It takes almost twice or thrice as long to irrigate my fields using a water pump. The diesel is being sold at almost Rs 100 per litre. Some years ago, it used to take a litre of diesel to irrigate a bigha of land. But now, it takes almost three litres to do the same,” Anoop Kumar Trivedi, a farmer from Madhia village in Sitapur, said.

“Even if we use bijli (electricity) to run our tubewells, it is not practical. The bijli is available only four to six hours a day, and the timings are irregular,” the farmer added.

Note: On June 15, 2022, violent clashes over irrigation left one farmer dead in Sitapur.

‘Unsustainable’ irrigation practices

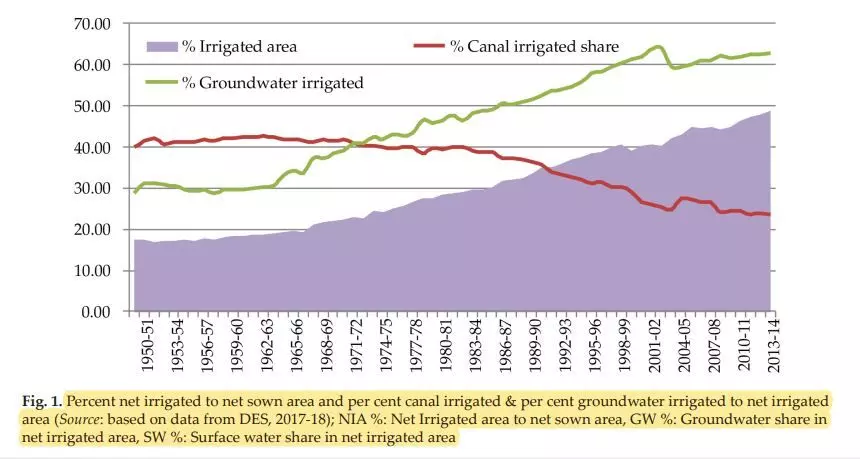

Venkatesh Dutta of Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University said that the manner in which agriculture is being practised across the country needs a major revamp. Groundwater reserves must be protected and conserved. The following graph below shows how the share of groundwater in irrigation has increased in the country.

“There is a popular opinion that constructing ponds can replenish the groundwater reserves. But along with that, we need to be specific about where we build these ponds,” he said. “What I suggest is that ‘water sanctuaries’ should be set up in areas where the rainwater naturally sieves down the ground,” he added.

“A water sanctuary might not look like an attractive tourist destination as it is simply an open field but that is how nature replenishes groundwater. It doesn’t require some super-structure to be built in order to recharge the aquifers,” the professor pointed out.

Source:https://krishi.icar.gov.in/jspui/bitstream/123456789/34362/1/irrigation_rajni_preprint.pdf

Dutta also highlighted that the cultivation of water-guzzling cash crops like sugarcane and mentha one season after another is detrimental not only to the shallow aquifers but also to the soil of the region.

Also Read: Fish farming comes to the rescue of UP farmers who suffer regular crop losses

He stated that the cultivation of sugarcane in western Uttar Pradesh and mentha in Barabanki district might provide good returns to the farmers but growing of a single crop is detrimental to the soil quality at large.

“Mono-cropping can make the soil barren after a while. Nature has not created land for only one type of plant to thrive on it. But unfortunately, temporary gains have lured the farmers to cultivate cash crops no matter how their soil or topography is,” Dutta said.

With inputs from Virendra Singh in Barabanki and Pratyaksh Srivastava in Lucknow.