One of Vidya Devi Soni’s earliest childhood memories is watching her mother make Mandana on the walls and floor of their house. Seeing Vidya intrigued, her mother Sumitra guided her into the world of Mandana, a traditional folk art form. That is how Vidya, from Rajasthan’s Bhilwara, drew her first Mandana on the wall of their village house at the age of 11.

In this fast-changing world where mud houses are rapidly turning into concrete houses in villages, this art form is on a rapid decline. Vidya Soni is one of the very few who still practice Mandana, one of the oldest folk art forms of India.

Mandana art form is unique for another reason as well – it is passed on from mothers to daughters. The reason behind this, said Dinesh Soni, Vidya’s son, is that taking care of the house has traditionally been seen as a woman’s responsibility. Mandana’s beauty lies in its raw and rustic nature that people, mostly women, adorn their houses with. “And so Mandana, which essentially means beautification, was seen as an art form related to women,” he said.

Most art forms, over the ages, break free from the gender barrier. This includes the ones traditionally restricted to men like Phad scroll painting of Rajasthan or Rogan art of Kutch. These are now being encouraged among women as well. Mandana, similarly, did not remain restricted to women alone. Dinesh Soni, for instance, practices Mandana too.

Mandana in everyday life

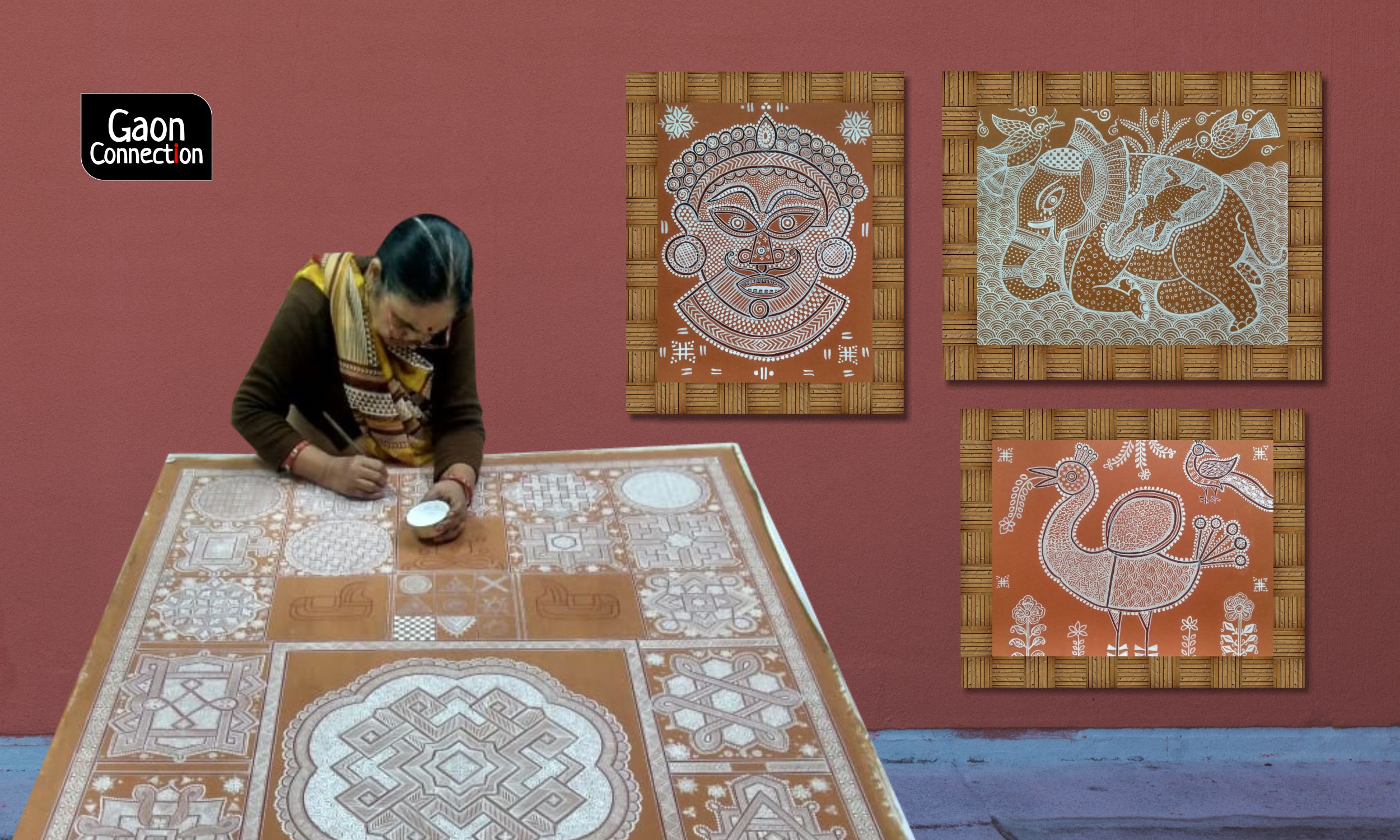

Mandana is drawn on the walls and floors of mud houses. Vidya’s art was inspired by nature and by all that surrounded her. “I had the best teacher – my mother,” Vidya, now 71, told Gaon Connection.

However, Mandana is not just about beautification. Attracting good omen is another of its principal aims. “Cosmic subjects, magic, those related to gods and goddesses, are all important themes of Madana and there are different Mandanas for different occasions,” Dinesh said. Holi, Diwali, and Gangaur, celebrated mainly by women in Rajasthan, have different Mandanas to signify the occasion.

Significant occasions in the family—like a wedding, or the birth of a child—again has a different painting. “Even the art on the walls and the floor are different,” he said. “Most of the nature-inspired art, like trees and birds, kund (pond) and bawri (stepwells) are on the outer walls. On the floor, in the puja room, for instance, will be a diya, or a rangoli,” he explained. A Mandana on the earthen stove (chulha) would be made afresh every week and on the floor, every fortnight. The theme would depend on what inspires the woman.

Vidya remembers a lot of drawings themed around water, like the process of drawing water from wells and water bodies. Peacocks are another favourite theme, signifying its abundance in the landscape.

Elephants, again, are a common feature. “Some of the creatures, however, are hard to decipher from the older drawings,” Dinesh said, suggesting that the mythical and the real often intertwine in the artist’s mind.

Mandana, in a way, documents everyday life.

Mandana, a dying folk art form

Mandana requires just two ingredients: khariya mitti or a chalk solution that is white in colour, and the geru mitti ka lep or clay, and cow-dung plastered walls and floors. Traditionally, twigs or bare fingers were used to make the different shapes but, with time, brushes began to be used instead. Mandana survived the transition from twig to brush but, the disappearance of the mud houses threatened its existence.

This change in landscape is inevitable, believes Vidya. To preserve this age-old art form, she dedicatedly makes a Mandana painting on paperboard every day. Staying as true to the art as possible, she uses the same two natural ingredients which give the white and brown colour.

In another part of Rajasthan, in the Baran city, 68-year-old Koshilya Devi, is on a similar path of keeping alive her connection with Mandana art and conserving it. Like Vidya, she too paints on paperboards and has been making efforts to keep the art form alive.

There are many other art forms similar to Mandana in other parts of India. Chowk Purna of Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, and Warli of Maharashtra are some examples. “Mandana of Rajasthan uses a lot of geometric patterns and that is what sets it apart,” Dinesh said.

Vidya’s work adds to Mandana’s life

What surrounds Vidya, inspire the themes for her work. Most of the paintings she makes are sold, others adorn her home. “Many are given away as gifts,” she said warmly. The septuagenarian has also taken part in exhibitions in cities like Delhi and Mumbai. She has also received many awards at the national level for her work.

One of her recent works was on the pregnant elephant in Kerala that was killed after eating a fruit, filled with explosives, used as a snare for wild boars. “The day I read that news in the morning newspaper, I couldn’t stop thinking about the elephant,” Vidya said. “I was moved by the pain of the mother and wanted to capture it in my painting. I discussed it with Dinesh and then made a Mandana depicting the mother and the baby elephant in her womb, trying to capture their tadap (pain),” she added.

Pictures of the 11 x 14-inch, visually-arresting Mandana immediately invited attention. As people started reaching out to buy it, Vidya decided to auction it. “I wanted to use the money for a good cause, to help other artists,” she said. “And so, with the help of Dastkar (NGO which supports artisans), I auctioned the painting. It was sold for Rs 21,000.”

Vidya has made at least 300 paintings so far and teaches the art form to anyone who is interested. “I have taught many women; the interest level is waning,” she said. Among her five grandchildren, only one is keen on mastering the art form.

However, all hope is not lost. Vidya Devi Soni’s family, in its efforts to keep the art form alive, has joined hands with an Indore-based fine arts academy and has designed a course to learn Mandana art online. The one-month-foundation course is divided into six sections. “Through these efforts, I hope to keep the tradition of Mandana alive and flourishing,” Vidya told Gaon Connection.