Katahari and Bilahta (Panna), Madhya Pradesh

It is a dangerous road one has to take to get to the adivasi villages of Katahri and Bilahta located in the buffer area of the Panna Tiger Reserve. They are the last of the habitation after which the core of the tiger reserve in Madhya Pradesh begins.

During the monsoon rains it is almost impossible to get there. No vehicle will venture into the forest area as the rocky roads turn into a slushy bog where any kind of vehicle can get stuck. If they do, there is no way of calling for help as there is no mobile signal available there.

Watch Video

Balancing two plastic containers on her head and one steel pot in her hand, 60-year-old Ramdulaiyya daily walks two kilometres through the thick jungle to fetch water from a jhiriya (a local water source). The resident of Bilahta village trudges down a slippery, rocky, and steep slope to a pool of water below.

Usually it is the women, young, old, infirm and even pregnant whose job it is to fetch water needed for their household needs.

After filling water in multiple pots, she climbs up and walks back two kilometres to her village Bilahta.

“Please do something to get us water in the village itself,” Ramdulaiyya appealed. “We don’t know what wild animals we will encounter when we trek through dense forests to get to the jhiriya; there are tigers, leopards and bears that lurk there,” she told Gaon Connection.

Ramdulaiyya’s village Bilahta and three other villages close by – Katahari, Koni and Majhauli – are adivasi villages that fall under the Katahari-Bilahta gram panchayat, and are located right on the border of the core and the buffer area of the tiger reserve.

These tribal villages not just struggle for drinking water, but being in the buffer zone of the tiger reserve, they are also deprived of basic health facilities, metalled roads, and electricity.

“My father-in-law had dug the place to find water, and even today we come here for it,” Kusum Rani, an 80-year-old inhabitant of Bilahta, told Gaon Connection. She added that whether it was to bathe, wash clothes or collect water for the household, the villagers came there all the way through the forests. Even at her age, she had to go down there, she said.

Earlier this year in May, Gaon Connection, as part of its Paani Yatra series, had visited adivasi villages in Panna Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, where in the blistering heat women trekked for miles to fetch water. The monsoons have come and almost gone and the women continue their struggle as there is still no water in their tribal villages.

Water woes

“There are about 90 households in Bilahta and about 50 in Katahari with a total of 530 people living in them,” Chitrabhan Yadav, the head of the Katahari-Bilahta gram panchayat, told Gaon Connection. These villages rarely have any official visitors, other than forest officials dropping in to enquire about their well being.

The four tribal villages – Bilahta, Katahari, Koni, and Majhauli – have a total population of 1,600. Of these, adivasi inhabitants of Bilahta and Katahari share one jhiriya, whereas Koni residents have another jhiriya (an underground water source) as their water source. Majhauli has handpumps.

Water unavailability is perhaps the biggest woes of the tribal villages in the buffer zone. Usually it is the women, young, old, infirm and even pregnant whose job it is to fetch water needed for their household needs. And each and every day they brave tigers, leopards, bears and snakes in the dense jungles to get to the jhiriya, which is the sole drinking water source of these villagers.

Also, the same source of water downslope is used by the wild animals in the forests and they often come there to quench their thirst.

The jhiriya is the sole drinking water source of these villagers.

Also Read: A Midsummer Pipe Dream: Pipelines laid down and taps installed, but where is the water?

“As far back as I can remember, we have only had this one jhiriya as the source of water for our village. There has been no other source of water here,” Ram Singh Rajgond, a 65-year-old inhabitant of Bilahat, told Gaon Connection. “Politicians visit us only when there are elections round the corner, and we never see them again,” he added.

According to Ram Singh, the forest department had built stone and cement embankments around the jhiriya so that there was water through the year there. “The extra water flows off into a drain and that is where the villagers bathe, wash clothes etc.

“It is also the watering hole for the wild animals coming from within the forests. It is quite usual to see tigers, leopards and bears here…” the 65-year-old said. The animals sometimes linger on and sit by the water after quenching their thirst. “We are fearful of them, but our thirst needs to be quenched too,” he smiled.

Women always come in groups to collect the water. If they see any wild animals, they quietly turn back, Ram Singh said.

“There are handpumps in Katahari and Bilahta, but no water comes out of them, not even in the monsoons,” Chitrabhan Yadav, a panchayat karmi of Katahari-Bilahta gram panchayat, said. The villagers have no other option but to go to the jhiriya, he said.

No vehicles can come to the village as the roads are terrible.

No roads

The tribal villages are remote and even if anyone should fall ill, help is miles away.

For instance, Bilahta is nearly 70 kilometres from the district headquarters at Panna. That is the distance people have to travel if they need to meet government officials or visit the offices there to make any representation. When it rains, everything shuts down, and Katahari, Bilahat, Koni and Majhauli are completely marooned.

“In case of a health emergency, the nearest health centre is at Amanganj, 25 kilometres away,” Deepa Singh Gond, the only girl from Bilahta village to be in college, told Gaon Connection. Her college is 50 kilometres away and she is completing her education through distance learning.

“Even getting to the nearest road head involves a trek of eight to ten kilometres through the forest. No vehicles can come to the village as the roads are terrible,” the 20-year-old said. If one had to make a mobile call, one had to climb up trees in order to get the signal to do so, she added.

No health facilities, high IMR and MMR

There are about 14-15 villages in the buffer area of Panna Tiger Reserve. And of these, ten are tribal villages, including Katahari, Bilahta, Koni and Majhauli. These adivasi villages have a dismal record when it comes to the health of mothers and infants, Nita Rahul, assistant coordinator of Project Koshika, an initiative that works in Panna on maternal and infant health, told Gaon Connection.

“We are trying to bring down infant mortality rates in these villages from 2018-19. These villages are extremely backward,” Rahul told Gaon Connection.

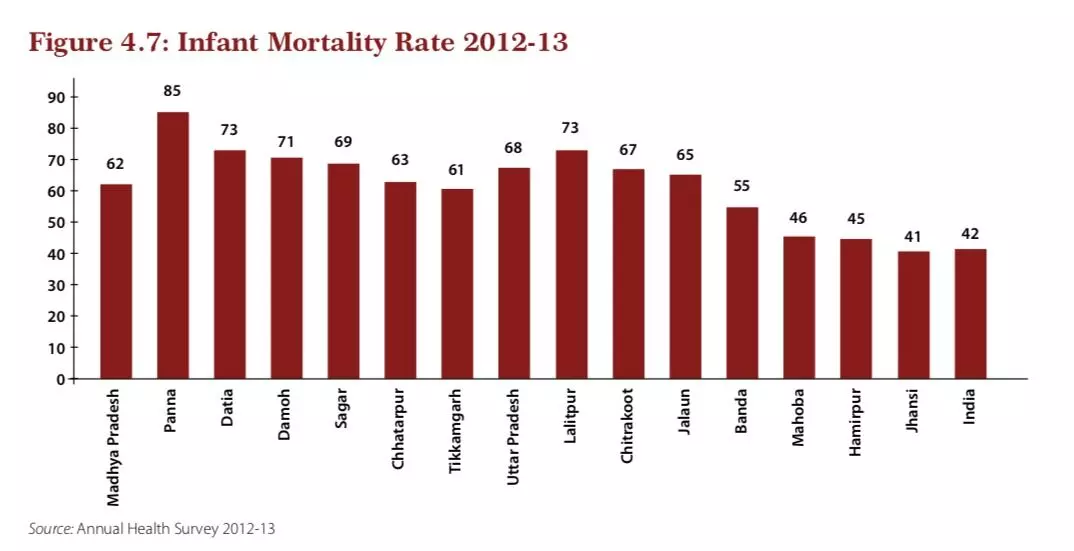

According to the National Family Health Survey-5 (2019-2021) of the Union ministry of health and family welfare, the infant mortality rate in Madhya Pradesh is 41.3 . It was 51.2 in the National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-2016). The infant mortality rate is the number of infant deaths for every 1,000 live births.

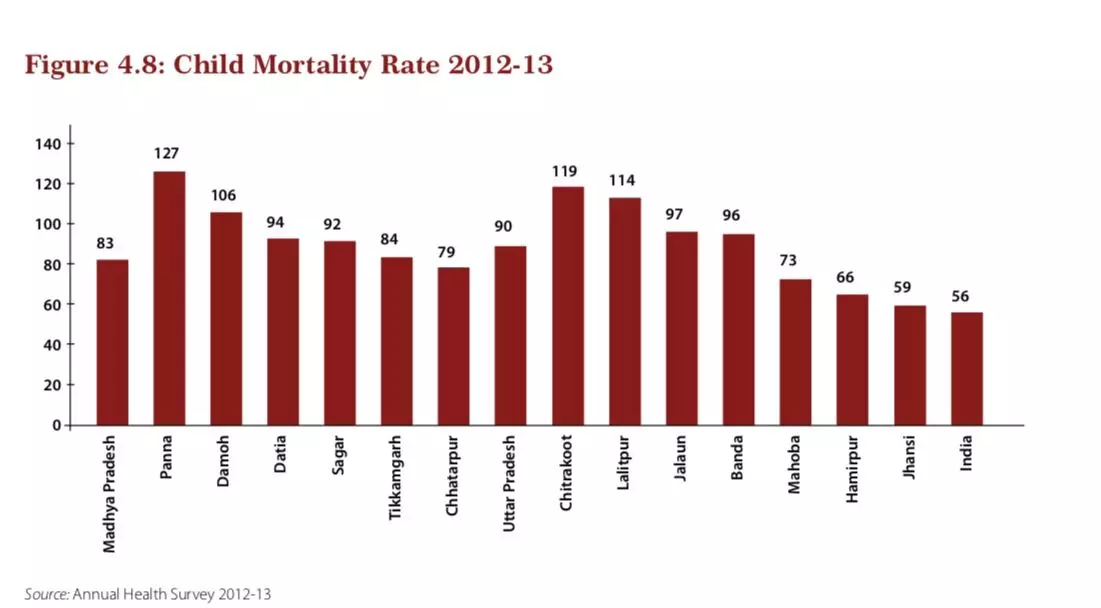

According to the Bundelkhand Human Development Report 2012, published by the NITI Aayog in 2015, the infant mortality rate (2012-13) in Panna was the highest in the state – 85 deaths per 1,000 live births. Similarly, at 127 the child mortality rate in the district was the highest in the state (see bar graph).

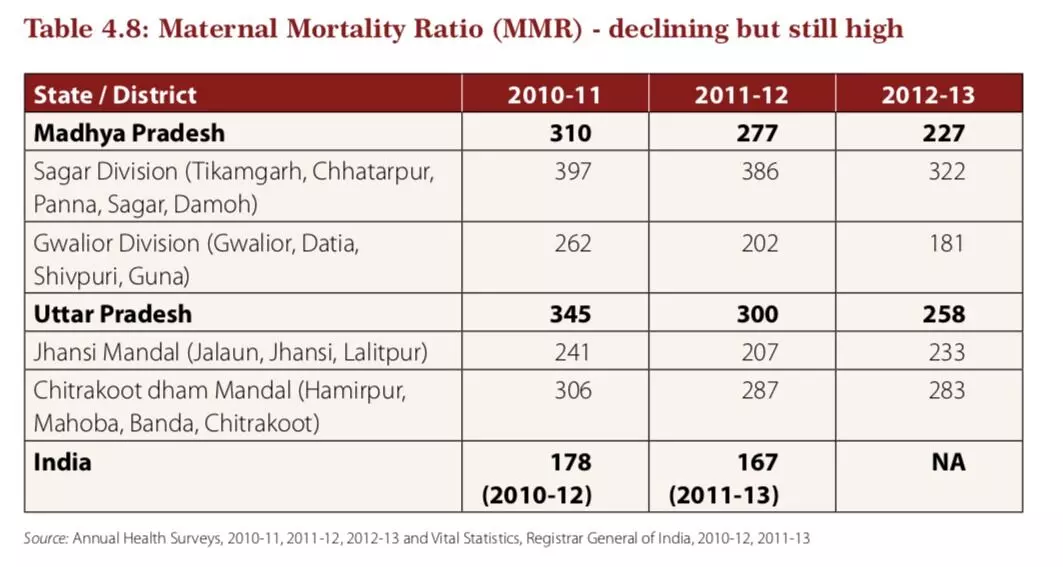

Similarly, the maternal mortality rate (MMR) in the region remains very high. According to the 2012 report, MMR in the Sagar division of Madhya Pradesh, which covers Tikamgarh, Chhatarpur, Panna, Sagar and Damoh districts, the MMR (2012-13) was 322! This was way higher than the average MMR of the state at 227.

Maternal mortality rate is defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births due to pregnancy or termination of pregnancy, regardless of the site or duration of pregnancy. The maternal mortality rate is used to represent the risk associated with pregnancy among women.

The reason for high infant mortality and maternal mortality in this region was the underdeveloped backward adivasi inhabited villages that had no health infrastructure whatsoever.

“The nearest community health centre to Katahari and Bilahta is Amanganj that is 25 kms away, and the district headquarters at Panna is 70 kilometres away,” Rahul pointed out. There are barely any roads and, in the past four years or so, Project Koshika has been working to help the village inhabitants reach Amanganj to get medical help by providing them vehicles, she said.

“Previously there was no organised help when the woman had to deliver her baby. Most deliveries were at home. But now, things are changing and Project Koshika is spreading awareness about maternal and infant health, and helping women with institutionalised birthing,” she said.

On being contacted by Gaon Connection, chief executive officer of Panna district, P L Patel, said that Katahari and Bilahta are revenue villages and should be connected through Pradhan Mantri Sadak Yojana. “But because these villages are surrounded by thick forests, we are unable to get permission from the forest department to build the road,” he said.

Speaking on the water issue, Patel said: “In the past, we had dug borewells, but no water could be found. We have found some points in the panchayat area where there is a possibility of finding water.”

“Since these villages do not have electricity supply, there is a proposal to set up solar water supply systems. For the same, funds have been sent to Akshay Urja office situated in Chhatarpur district,”Patel explained.

While the official files and funds move from one department to the other, 60-year-old Ramdulaiyya continues with her daily walk through the thick jungle to fetch water for her family.