India is the world’s largest producer of milk, pulses, and jute, and ranks as the second largest producer of rice, wheat, sugarcane, groundnut, vegetables, fruit, and cotton. Despite high levels of food production, the country ranks 94 out of 107 countries on the 2020 Global Hunger Index.

A large chunk of food grown by the Indian farmers fails to reach the consumers due to post-harvest losses. And figures for these losses vary. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has reported an annual loss of 40 per cent of fresh fruits and vegetables worth USD 8.3 billion in India. The central government’s Food Corporation of India pegs these losses at 15 per cent. While the figures for the losses vary, they are still alarming enough to demand urgent action to decrease hunger and malnutrition in the country.

Post-harvest losses translate into huge financial losses to the farmers. According to the Cool Coalition, every year, farmers in India incur nearly USD 12,520 million in post-harvest losses due to inadequate storage facilities and a lack of energy infrastructure. This is worrisome as almost 82 per cent of farmers in the country are small and marginal farmers with land holding of less than two hectares.

NITI Aayog’s Policy Paper – Doubling Farmers’ Income – published in March 2017, notes that an increase in farm output has not always resulted in a commensurate increase in farm incomes. “The experience (in reference to agricultural policy over the years that has focused more on increasing farm output and not as much on improving farmers’ livelihoods) shows that in cases, growth in output brings a similar increase in farmers’ income, but in many cases, farmers’ income did not grow much with an increase in output. The net result has been that farmers’ income remained low, which is evident from the incidence of poverty among farm households,” the report reads.

Post-harvest losses translate into huge financial losses to the farmers.

At the heart of improving farmers’ welfare lies improving their terms of trade – a goal (noted in the March 2017, NITI Aayog report as well) that can be achieved by increasing the country’s cold chain infrastructure as it gives farmers more latitude to bargain and hold back their crops until they are able to secure appropriate prices for it.

At present, between 25 per cent and 35 per cent of cultivated food is wasted due to a lack of proper refrigeration and other supply chain bottlenecks, and only six percent of the food produced in India currently moves through the cold chain.

At the beginning of 2020, there was a shortfall of 12.6 million tonnes of cold storage capacity in the country, as noted by the National Centre for Cold Chain Development (NCCD), an autonomous body set up by the Indian government to establish cold chains for perishable agriculture and horticulture produce.

To reduce post-harvest losses in the country, the Basel Agency for Sustainable Energy (BASE) and Empa (The Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology), are implementing a project – Your Virtual Cold Chain Assistant (Your VCCA). By using data science, digitalisation, and business model innovation, Your VCCA aims to provide smallholder farmers with access to clean, decentralised cold storage facilities as well as post-harvest intelligence.

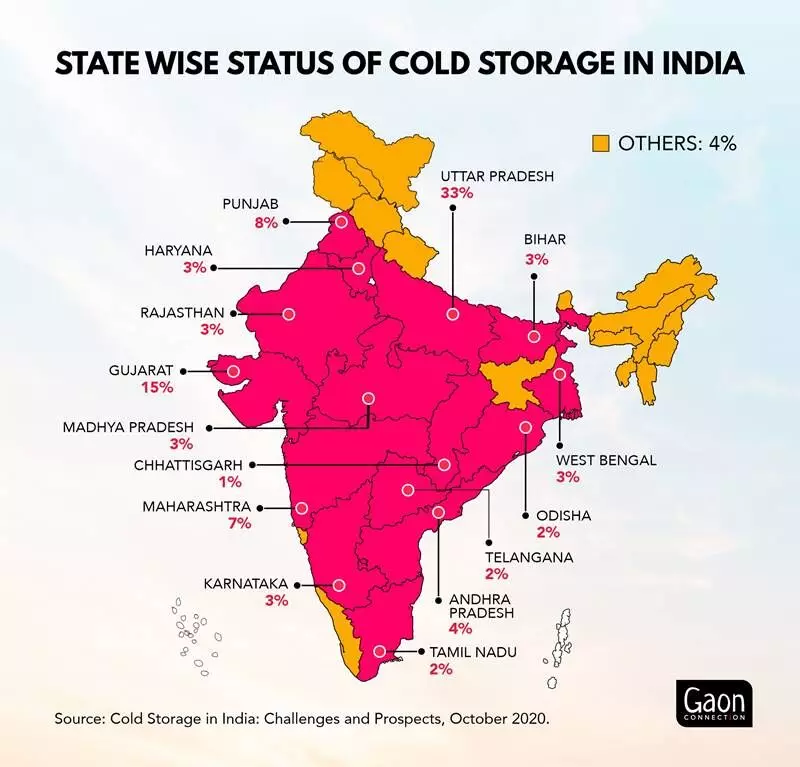

There is a huge imbalance in state-wise distribution of these cold storage facilities. Almost 33 per cent of the national cold storage capacity is located in Uttar Pradesh, but is largely used for storing potatoes.

“Globally, a third of the fresh produce is lost due to gaps in the cold chain infrastructure. Climate friendly cooling technologies are available, but their deployment is limited due to the lack of reliable access to energy, high-upfront costs, unavailability of proper maintenance, and limited financing options and know-how. Innovative business models can help to overcome these barriers,” Thomas Motmans, senior sustainable energy finance specialist at BASE, told Gaon Connection.

BASE and Empa first identify local partners who are willing to offer ‘cooling as a pay-per use model’. Currently, the Your VCCA project is being rolled out at three locations in India – Muzaffarpur in Bihar, Rourkela in Odisha, and Shiladesh (Shimla district) in Himachal Pradesh. These pilots are being implemented in partnership with local clean technology companies with the aim to cut down post-harvest food losses and increase farmers’ income. These include Cool Crop Technologies Private Limited (Himachal Pradesh), Koel Fresh Private Limited (Odisha), and Oorja Development Solutions Limited (Bihar).

Your VCCA project: Minimising post-harvest losses

Your VCCA project was launched in India in January 2021. The aim of the project is to contribute to food security in the country, reduce post-harvest loss, and increase the incomes of smallholder farmers.

The Your VCCA project includes two components: an innovative pay-per-use business model, called Cooling as Service (CaaS) to overcome the market barriers hindering the adoption of cold storage among farmers, and a data-science-based mobile application, called Coldivate, that facilitates the CaaS’ implementation.

Currently, 95 per cent of the cold storages are owned by the private sector, three per cent by cooperatives, and the remaining two per cent by public sector undertakings.

Unlike the traditional selling model, in which farmers purchase a cooling unit from a company, own and maintain it till the end of its life cycle, the servitisation approach on which the Cooling as Service model is based keeps the ownership of the cold room (typically solar-powered and decentralised) in the hands of a local provider. In other words, the operator pays for the cold room’s operations and upkeep in exchange for a nominal fee from the end-users, such as marginal farmers and small-time traders. The servitisation model spares customers the upfront investment of installing expensive equipment, minimises operation and technology risks, and reduces the overall utility costs.

By leaving the responsibility of equipment maintenance, repairs and updates to the technology providers, end-users can pay undivided attention to their core business. The use of servitisation to facilitate access to energy-efficient and sustainable technologies helps countries to address the need for cooling while contributing towards their climate targets.

Coldtivate app

The other component of the Your VCCA project – the Coldtivate app – ensures that once farmers have access to cooling units, they are able to maximise the benefits reaped from its usage. Coldtivate serves this aim by predicting the extended shelf-life of the crops (from cold storage vis-a-vis storing it at ambient temperatures) based on real-time sensor data (temperature and humidity in the cold room) and the initial quality of the produce. By leveraging this information, farmers have an alternative to distress-selling at the end of the day and can store their crops for longer to secure better off-season prices, while still being mindful of selling their produce before its quality deteriorates.

The Coldtivate app ensures that once farmers have access to cooling units, they are able to maximise the benefits reaped from its usage.

“The app is designed keeping the needs of three audiences in mind – the local entrepreneurs offering cold storage facilities, community members operating these rooms and, most importantly, the smallholder farmers and petty traders using the rooms. The app is currently used by the companies offering the cooling services, and it will be made available for the farmers by the end of the year,” informed Simran Singh, capacity building officer at BASE.

“The current version of the app helps accelerate the deployment of the business model through two key features: digitalising the check-in and check-out of crates in the cold room, and predicting the remaining shelf-life of the crops,” explained Roberta Evangelista, data science and digitalisation specialist at BASE.

In addition to predicting the shelf life of the stored crops, the newer versions of the app will include market price forecasting. The app will forecast the price of commodities across different markets in the vicinity of the cold rooms. This information, combined with the remaining time left for pick up, will provide insights to cold room users on when and where to sell the crops in storage.

“In the absence of an app, the room operations are conducted manually by the technology providers, are more prone to error, and cannot be easily monitored by the users. Digitalising the cold room transactions is a very important step to make the business model seamless and generate trust among farmers to use the cold rooms,” Evangelista added.

The Knowledge Hub integrated in Coldtivate contains information about the optimal storage temperature and average storage time for each commodity, and will be regularly expanded and enriched to reflect the best practices in post-harvest management as per latest research. To ensure that cold storage users and operators always have access to this crucial information, the Knowledge Hub will be made available offline as well.

The Knowledge Hub contains information that facilitates the operations and use of cold rooms, allowing operators to ensure that all crops are handled with care and maintain high quality (so that farmers can get fair prices).

12.6 million tonnes shortfall of cold storage capacity

The importance of the Your VCCA project can be gauged from the fact that despite being the world’s largest producer of milk, second largest producer of fruits and vegetables and a substantial production of marine, meat and poultry products that are temperature sensitive and require specific temperature ranges to be stored and transported, India has a huge shortfall in cold storage facilities for these products.

A 2019 Policy Brief No 5 by the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences concluded that storage was the major cause of post-harvest losses for all kinds of food in India. Perishable goods losses are due to surplus stock that exceed storage capacity; usage of improper storage methods; constraints in liquidation of excess stock; and a lack of interest from the private sector in investing in cold storage infrastructure.

In September 2020, the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare under the Government of India released a statement about the country’s cold storage capacity and infrastructure. According to its press release, there are only 8,186 cold storages with a combined capacity of 37.425 million metric tonnes available in the country for storing perishable fruits and vegetables. As noted earlier, at the beginning of 2020, there was a shortfall of 12.6 million tonnes of cold storage capacity in the country

Currently, 95 per cent of the cold storages are owned by the private sector, three per cent by cooperatives, and the remaining two per cent by public sector undertakings.

Sixty-eight per cent of the capacity is used for potatoes while 38 per cent is multi-commodity cold storage capacity. In most rural areas, there is a greater need for multi-commodity rooms as farmers are increasingly engaging in double and multiple cropping. Also, the availability of cold rooms incentivises farmers to move beyond growing single crops (generally cash crops).

The upcoming cold rooms need to be designed for multi-commodity storage. Your VCCA attends to this existing gap in multi-commodity rooms by facilitating the deployment of decentralised rooms to store different types of horticultural crops.

The typical hurdle with running multi-commodity cold rooms is knowing what temperatures to maintain for different combination of crops, which crops not to store together, and gaining expertise in handling different types of fruits and vegetables. To equip cold room operators with this information, Coldtivate’s Knowledge Hub provides information on ideal temperatures to store different combinations of crops on, which crops not to store together, and how to handle different crops in the post-harvest phase.

“Our country needs a massive growth in its cold storage system. As the majority of the cold storages store only potatoes, we require multi-commodity storages and that too in proximity to farmers,” M K Thakur, chairperson, Mithila Union in Darbhanga, Bihar, told Gaon Connection. Mithila Union operates under the Bihar State Vegetable Processing and Marketing Scheme to create an efficient supply chain network.

According to Thakur, it is more difficult to keep a cold storage functional in the country, due to lack of working capital. This problem highlights the need for business model innovation to incentivise and enable the uptake of cold rooms, especially among smallholder farmers. Despite the higher upfront cost of solar-driven cold rooms, these are also less expensive to operate compared to grid-based or generator-driven cold rooms.

The model further aims to integrate forward market linkages (from cold rooms to consumers) to ensure sales for farmers, which is needed to crystallise farmers’ trust in the room and bring in the revenue to keep the rooms running.

Ruchika Singh and Shweta Lamba from World Resource Institute, India analysed post-harvest losses in a paper published in 2021 titled Food Loss and Waste in India: The Knowns and The Unknowns.

“We identified three main reasons for post-harvest losses: poor storage facilities, poor transportation and harvesting techniques,” Singh told Gaon Connection.

Meanwhile, a Canada-based investment management company, Colliers, forecasts a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14 per cent in the Indian cold chain sector by 2023. This upward trend is driven by a surge in online grocery, pharmaceuticals sales and the COVID-19 vaccination drive.

State-wise cold storage network

There is a huge imbalance in state-wise distribution of these cold storage facilities. Almost 33 per cent of the national cold storage capacity is located in Uttar Pradesh, but is largely used for storing potatoes.

About 15 per cent of the cold storage (for horticulture produce) is in Gujarat, notes an October 2020 paper, Cold Storage in India: Challenges and Prospects. This is followed by Punjab, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Odisha where the cold storage capacity is at least more than 100,000 tonnes per horticulture produce of the state. However, states, like Maharashtra and Karnataka with large amounts of exportable produce do not have adequate cold storage capacity. Bihar, Chhattisgarh, and West Bengal fare the worst in terms of cold storage as per horticulture produce.

The rising government interest in the issue of setting up cold storage facilities in the country, and a shift to decentralised cooling can help remedy the imbalance in state-wise distribution of these facilities.

This story, the first in a three-part series, has been done in collaboration with the Basel Agency for Sustainable Energy. The next two stories of the series, focus on the the Your VCCA projects in Muzaffarpur (Bihar) and Rourkela (Odisha).