Kalyanpur (East Bardhaman), West Bengal

Dinonath Ghosh, a farmer for more than four decades believes that this must be the worst paddy farming season he has experienced. The 62-year-old farmer lives in the remote Kalyanpur village in West Bengal’s East Bardhaman district, which is also known as the ‘rice bowl of Bengal’ due to its high paddy production. But this year, the crop is likely to suffer heavy damages.

“The poor monsoon rainfall during the sowing season of aman paddy has hit us badly,” Dinonath told Gaon Connection. The aman paddy variety is sown in June-July and harvested in winter in November-December.

Farmers in East Bardhaman district depend heavily on the water provided by the Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC), a government owned enterprise. But, due to deficient rainfall this monsoon, there is less water in the dam and this has forced DVC to cut short the water supply, the farmer complained.

“Our fields do not have sufficient water and I have sowed paddy in just half of the total area. We are now dependent on groundwater for farming,” the worried farmer said.

Dinonath Ghosh

The DVC supplies irrigation water through its dams in West Bengal and Jharkhand, but poor rainfall has depleted the water levels in the reservoirs. Between June 1 and August 10 this year, West Bengal has reported a rainfall departure of minus 24 per cent and Jharkhand at minus 48 per cent.

According to agriculture department officials in West Bengal, while usually DVC releases 180,000 cusecs of water in July, this year it has released just 70,000 cusecs of water for the month.

“We are already facing a poor monsoon and less water from DVC has added to the crisis. It is difficult to sow the aman paddy in the entire cultivable land due to the water shortage,” Ashis Barui, deputy director, agriculture (admin), East Bardhaman, told Gaon Connection.

Durgapur Barrage built across the Damodar River at Durgapur in Paschim Bardhaman district. Photo: Damodar Valley Corporation

West Bengal is India’s top rice producing state. Deficient monsoon rainfall is likely to affect rice production in the state. Other rice growing states in the Indo-Gangetic plains, such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jhrakhand, have also received deficient rainfall leading to distress among millions of paddy farmers.

As part of our new series – Paddy Pain – Gaon Connection reporters travelled across the key paddy producing states to document the impact of deficient monsoon rainfall on the paddy crop this year. And the reports they have come back with seem worrisome, as paddy farmers are reportedly staring at huge crop losses. And these local crop losses have a global impact as a drop in rice production in the country is likely to disrupt global food supply, as India is the world’s top exporter of rice.

This story from East Bardhaman in West Bengal is the second in the Paddy Pain series. The first story was from Uttar Pradesh that has reported minus 40 per cent rainfall departure this monsoon season so far.

“We get water from DVC that helps us in sowing but the situation is pathetic this year. We have no alternative but to depend heavily on groundwater which is drawn through submersible pumps and supplied to our fields through the network of pipes,” Joseph Marandi, a paddy farmer from Kalyanpur village, told Gaon Connection.

According to Marandi, the pumps run on electricity and the owners charge Rs 100 per hour as rent. “We need at least eight to ten hours of water every day during the sowing season. It takes a huge toll on the sowing cost and hits our income,” the paddy farmer said.

Rice is the most important staple food of the country consumed by about 65 per cent of the population, as noted in a June 2021 paper. It is grown in almost all the states, however, the major rice producing states with respect to their share in total rice production of the country during 2018-19 are West Bengal (13.79 %), Uttar Pradesh (13.34 %), Andhra Pradesh including Telangana (12.84 %), Punjab (11.01 %), Odisha (6.28 %), Chhattisgarh (5.61 %), Tamil Nadu (5.54 %), Bihar (5.19 %), Assam (4.41 %), Haryana (3.88 %) and Madhya Pradesh (3.86 %).

In West Bengal, Bardhaman region is known as the ‘rice bowl of Bengal’. According to officials of the agriculture department, collectively, there are over 400,000 hectares under paddy cultivation in east and west Bardhaman districts, and nearly 550,000 farmers grow paddy. The district produces over two million metric tonnes of paddy annually. West Bengal produces about 15.57 million metric tonnes annually.

East Bardhaman is the major rice producing hub with around 381,000 hectares of land under paddy cultivation and 500,000 farmers involved in paddy farming. The average production per hectare stood at 5.2 metric tonnes last year. The sowing season starts from the third week of June and continues till October 15.

West Bardhaman has around 19,000 hectares under paddy farming and 50,000 farmers are involved in it.

“The rains in June were half of what we received last year. We received about 113 millimetre of rainfall in June while last year in the same month there was 226 millimetre of rainfall. In July this year we received 105 millimetre of rainfall while last year it was around 270 millimetre,” Barui from East Bardhaman said.

According to him (as of August 4), sowing was complete in 141,000 hectares of land as compared to 284,175 hectares last year. Clearly, a sharp decline in paddy acreage in East Bardhaman district this year.

Similar situation prevails in West Bardhaman. “We have got 47 per cent deficit rainfall this year which has limited our sowing area to just 4,000 hectares as compared to 28,000 hectares last year till this time,” Sagar Bandyopadhyay, deputy director, agriculture (admin), West Bardhaman, told Gaon Connection.

He said if the skies continued to remain cloudless, the government would have to resort to a contingency measure. “The farmers may have to plant maize and black gram if the situation deteriorates and there is not enough rain,” Bandyopadhyay added.

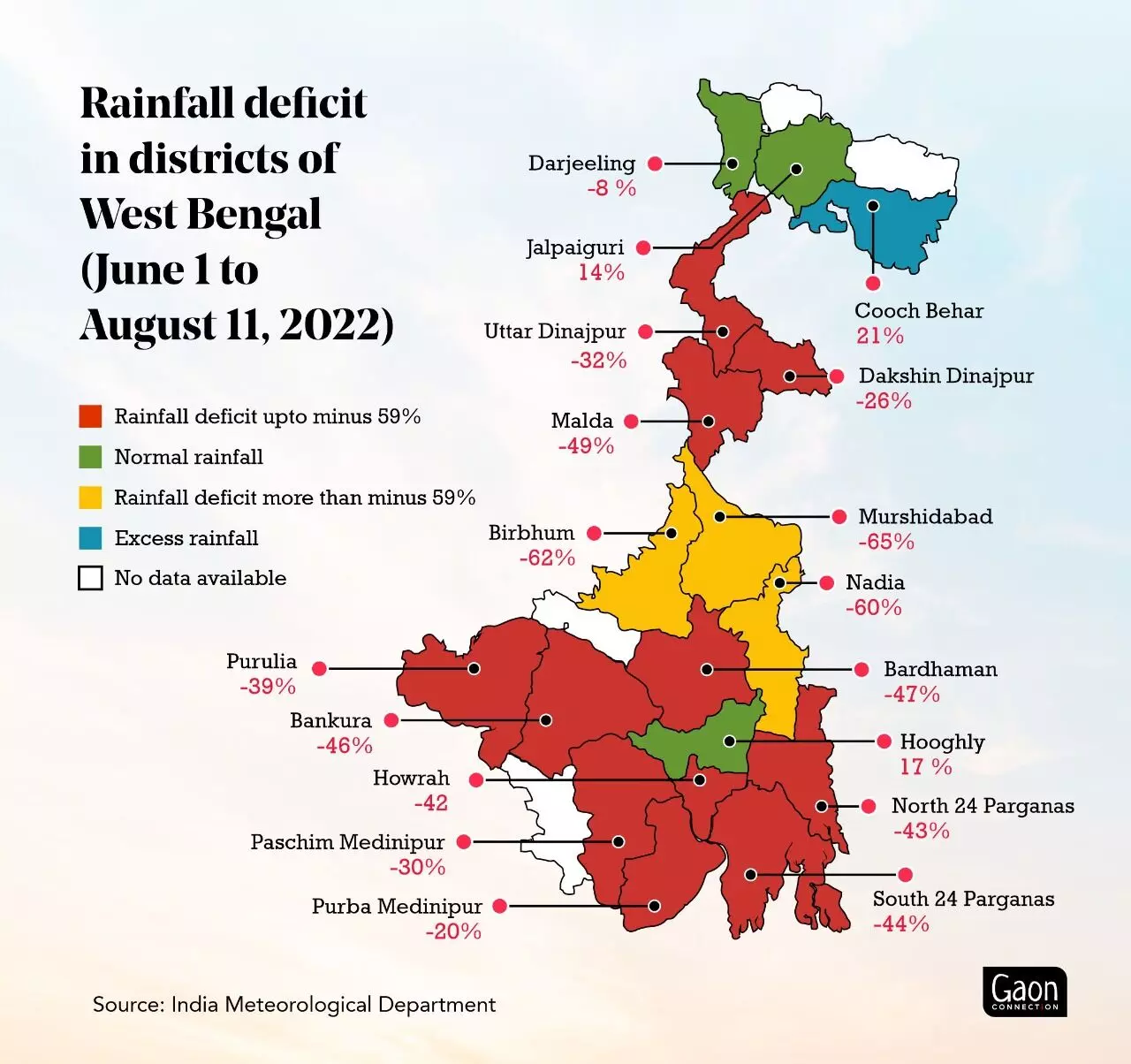

Other districts in the state have also reported deficient rainfall. For instance, Nadia, Murshidabad, Birbhum and Bankura have reported deficient rainfall of minus 60 per cent, minus 65 per cent, minus 62 per cent and minus 46 per cent, respectively.

Deficient rainfall has led to rural distress. “We do not get any loans from the banks and have to depend on moneylenders to give us loans in exchange for the paddy harvest. But if the production takes a hit, it will be very difficult for us to repay the loan,” 45-year-old Samar Ghosh, who cultivates paddy in 0.80 hectares of land in East Bardhaman, told Gaon Connection.

The ramifications of low production of paddy in India can potentially affect the global supply of rice as well.

Not just farmers, the farm labourers have also been hit hard by the lack of rains. “We are usually busy this time as farmers employ us to assist in sowing paddy seeds. But this year, there is hardly any work. I have worked barely ten days in the past month, how will I feed my family,” asked a worried Krishna Baski, a farm labourer.

Submersible pumps and groundwater

Farmers have urged the power department not to cut off the power supply even if there are pending bills, “We are in deep distress due to poor rainfall and depend on submersible pumps for irrigation. The power officials are snapping the power supply of those farmers whose bills are pending,” Alok Biswas, a 53-year-old farmer in East Bardhaman district, told Gaon Connection.

Biswas said the farmers had appealed to the officials to restore power and assured them that they would clear all bills as soon as the situation became normal. “At least we can then run our submersible pumps to save our paddy crop,” he said.

Ashis Barui, deputy director, agriculture (admin), East Bardhaman said that power officials had been directed to restore electricity supply. “We understand the seriousness of the situation. Most of the pumps here run on power and there are hardly any diesel pumps. We have also distributed around 30,000 solar pumps to the farmers in the district,” he added.

Farmers have urged the power department not to cut off the supply even if there are pending bills as they use electricity-operated pumps to irrigate their fields.

Question of food security

Experts say that too much dependence on groundwater might affect the sowing the next season too. “Bardhaman depends on irrigation for farming but the continuous drawing of groundwater without rainfall to recharge the natural aquifers can take its toll on the sowing of the rabi (winter) crops,” Madhab Chandra Dhara, former joint director of agriculture, based in Hooghly, told Gaon Connection.

“The low production of aman paddy might also affect TPDS (Targeted Public Distribution System) through which the government distributes food grains among poor households. The farmers will most likely save the paddy for themselves rather than selling it to the government,” he pointed out.

Global food crisis?

The ramifications of low production of paddy in India can potentially affect the global supply of rice as well. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, India is the largest exporter of rice in the world and contributes 40 per cent to the global supply.

As per a December 16, 2021 press release issued by Press Information Bureau, in 2020-21, India’s rice exports rose by a whopping 87 per cent to 17.72 million tonne (MT) from 9.49 MT achieved in 2019-20. “In terms of value realisation, India’s rice exports rose by 38 per cent to USD [United States Dollar] 8815 million in 2020-21 from USD 6397 million reported in 2019-20. In terms of Rupees, India’s rice export grew by 44 per cent to Rs 65298 crore in 2020-21 from Rs 45379 crore in the previous year,” the press statement mentioned.

The looming crisis on rice exports in India is reminiscent of a similar situation six months ago when early heatwaves reduced the production of wheat which forced the Indian government to call off exports in order to meet the domestic demand.