Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the farmers on the importance of natural farming today, December 16, during the valedictory session of the three-day National Summit on Agro and Food Processing in Anand, Gujarat via video-conferencing. Over 5,000 farmers attended this summit, and many more joined it virtually through Krishi Vigyan Kendras and ATMA (Agricultural Technology Management Agency) network in states across the country.

नैचुरल फार्मिंग से जिन्हें सबसे अधिक फायदा होगा, वो हैं देश के 80 प्रतिशत किसान।

— PMO India (@PMOIndia) December 16, 2021

वो छोटे किसान, जिनके पास 2 हेक्टेयर से कम भूमि है।

इनमें से अधिकांश किसानों का काफी खर्च, केमिकल फर्टिलाइजर पर होता है।

अगर वो प्राकृतिक खेती की तरफ मुड़ेंगे तो उनकी स्थिति और बेहतर होगी: PM

“Zero budget natural farming”, which promotes the use of the desi (indigenous breed) cow, its dung and urine for agricultural purposes, is turning out to be a promising tool to minimise the dependence of farmers on purchased inputs, such as chemical fertilisers and pesticides, and reducing the cost of production, thereby making farming profitable.

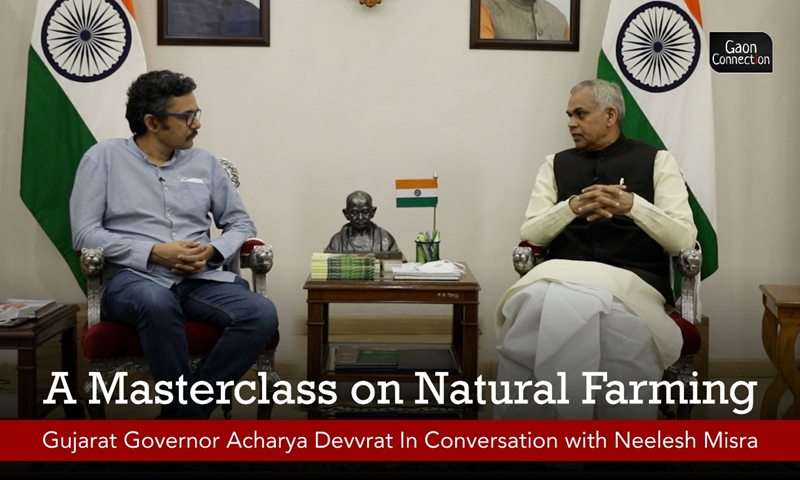

Acharya Devvrat, the 62 year-old Governor of Gujarat, is not only a strong proponent of natural farming, but also its active practitioner.

In a conversation with Neelesh Misra, founder of Gaon Connection, Governor Devvrat builds a strong case for adopting natural farming on a large scale in the country, which, he said, will not only bring profit to the farmers, but also maintain soil health and reduce the growing disease burden due to consumption of chemical- laced food.

Also Read: Non-pesticidal management in agriculture is a win-win for farmers and consumers

What made you adopt natural farming?

I was the pradhan acharya (principal) of a gurukul in Kurukshetra for 35 years. We had residential students from across the country, and we grew our own food on 200 acres (1 acre = 0.4 hectare) of land that belonged to the gurukul.

Like regular farmers, we used chemicals extensively on the 200 acres of land. Once, a farm labourer lost consciousness as he sprayed pesticides on the land. He recovered, but that incident bothered me to no end.

The pesticide was so poisonous that it harmed the sprayer. And, here we were spraying copious amounts of it on the land the produce of which we fed the students.

I realised it was so wrong. I decided to go organic.

The switch from chemical farming to natural farming

I prepared to turn five acres of the land into organic. In the first year, I got next to nothing as yield. In the second year, I got about 50 per cent of what I should have got as yield, and in the third year the yield went up to 80 per cent. However, the cost of farming remained the same and it did not come down.

The expenses were the same and the yield was below par. How would a farmer with say only an acre or two survive going organic?

Also Read: Using indigenous seeds to sustain livelihoods, fight climate change and pay off loans

Just as I contemplated going back to my pre-organic way of farming, I met agriculturist Subhash Palekar (a torchbearer for natural farming who has written several books on the model). Palekar spent five days meeting the farmers involved and, from him, I learnt the nuts and bolts of natural farming.

I began to follow Palekar’s specific instructions on farming on the five acres of land. What happened next was nothing short of a miracle. I got a healthy yield, there were no weeds and my expenses came down.

I decided to go with natural farming on 100 acres of land. I had tried all three kinds of farming, inorganic, organic and natural, and the last one was the most successful.

Why has organic farming not picked up in the country despite the best efforts of the government, agri scientists and farmers?

Hari Om, an agricultural scientist from the Kurukshetra Vigyan Kendra, Hissar, showed me an eye-opener of a report.

To get the best yield of wheat, rice and sugarcane (that are grown the maximum in order to fill up the nation’s silos), each acre of land that is cultivated requires 60 litres of nitrogen and several tonnes of chemical fertilisers.

Also Read: Should cows be declared the national animal of India?

In organic farming, one acre of land would require 300 quintals of gobar (cowdung) and 60 litres of nitrogen. How will the farmer get so much gobar? He will need 15 heads of cattle to produce the required quantity of gobar. How can he afford that? There is also the need of nearly 150 quintals of vermicompost that takes months to get ready and involves a lot of labour and expenses. The organic farmers get earthworms from abroad that are high maintenance and die easily.

Also, the farmer will have to wait for at least three years before his land will start yielding a respectable amount of produce. Which farmer can afford to wait for three years?

What about natural farming?

Natural farming has no such restrictions. It uses nothing that is store-bought. It uses jeevamrut – natural fertilisers made from cow dung and urine of native cattle species.

All that a farmer requires is a healthy native breed of cattle which produces eight to ten kilograms of dung and about the same quantity of urine a day. Jaggery and chickpea flour is mixed with this and stored in a drum in the shade. All the farmer has to do is stir the mixture twice a day, clockwise, and in six days fertiliser enough for one acre of land is ready.

On testing it was found that one gram of dung from native species of cattle contained more than 300 crores (three billion) of useful bacteria in it; it was a treasure trove of minerals.

Also Read: Bringing the desi back into cotton

How is jeevamrut used?

The prepared solution is spread on the field. And like a spoonful of curd can convert a bowl of milk into curd, the jeevamrut does the job of spreading its goodness through the soil. It is a great nitrogen fixer and nourishes the roots of the plant. There is no need for DAP or any other store-bought chemicals.

All the nourishing ingredients are already present in the soil and the jeevamrut just acts as a catalyst to get them working. It does the work of a cook in a kitchen. The ingredients are all present in the kitchen, it requires someone to put them together to produce food.

It is no secret that chemical fertilisers strip the soil of its nutrients over a period of time, and if we do not stop that, we will leave behind barren land to the future generation. Chemicals kill the bad pests, but along with it they also decimate the friendly bacteria that are essential to the plants too. They kill the earthworms in the soil that are our friends.

But, it is still not too late. We still have our good friends in the soil, just waiting to help us. And help us they do, in conserving moisture, water and reducing global warming.

When a farmer unties his or her cow, she wanders around leaving behind dung here and there. If the dung is left where it is and if it is flipped around after a day or two, there will be pores on the underside indicating how bacteria has burrowed into it to be nourished. So, when we put jeevamrut into the soil, the bacteria emerge to the surface to feed, be nourished and in turn nourish the soil and plants.

Protecting and breeding native cattle will be beneficial not just to the community of farmers but will also fortify the soil. So much money is spent by the government on subsidising chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Imagine the savings on that.

What about the earthworms?

Native earthworms are good. They burrow up to eight to ten feet into the soil creating tunnels that allow oxygen to enter the soil. Meanwhile, the earthworm droppings provide rich nutrients to the plants.

I know that in just one acre of my land there are lakhs of earthworms working day and night and softening the soil, turning it, and bringing up minerals to nourish the soil inside out. These same tunnels allow water to seep in when it rains. This does not happen on grounds where chemicals have hardened to such an extent that no water can seep in, and if it does it creates contaminated groundwater.

Mulching is another natural farming method where crop residue is spread out on the land to keep the moisture in. This keeps the soil moist and sometimes that is all that the farmer needs, not excessive water. A lot of water use can be saved this way.

Also Read: A new bioformulation, Halo-MIX, offers hope to restore fallow land and increase crop yield

Earthworms that work in the night in darkness, because in the day they can be easy prey for birds, etc., will also work well under the mulch as it is dark and conducive to them to do their job undisturbed. The jeevamrut draws nutrition from the mulch and works more efficiently to transform the mulch into fertiliser. Mulching also prevents too many weeds from growing.

What works in jungles should work in my field. No one waters the plants in the forests, no one tends to them or fertilises them or sprays pesticides to keep them safe. Yet, they thrive. Nature can work the same way on our lands as she does in forests, if we allow her to.

Have you tried all these methods?

I speak from personal experience. I had leased some land to farmers. Three years ago, they said they could grow nothing on the land. I consulted agricultural scientists who took soil samples from that land to test and the report that came back said the soil quality was very poor.

I decided to use jeevamrut on that land and used five quintals per acre, before sowing paddy. The first crop yielded 21 quintals of paddy per acre and the second crop yielded 28 quintals per acre. A year later the soil of the land was tested again and this time the test reports showed remarkable improvement to the soil that had become most fertile.

This year, the yield from that land has been 33 to 35 quintals per acre. While I was doing chemical farming, I got only up to 30 quintals per acre. My water consumption has reduced too and my cost of farming per acre has come down to Rs 1,000 per quintal while earlier it was between Rs 10,000 to Rs 12, 000 per quintal. All because I stopped using any chemicals on my land.

Scientists collected soil samples from farms that used chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Lab tests revealed that in one gram of the soil there were thirty lakh five thousand (about three million) organisms present in it. A similar test on soil from a land where natural farming was practised, each gram of soil had the presence of 161 crores (1,610 million) of organisms in it.

Just as chemical farming has led to global warming, natural farming can bring an end to global warming.

Natural farming in Himachal Pradesh

When I was the Governor of Himachal Pradesh (2015-2019), we took forward the idea of natural farming and nearly 50,000 farmers decided to follow it. Today, there are one lakh (100,000) farmers and counting who are practising natural farming in the Himalayan state.

In Gujarat, Dang district has been declared a ‘natural’ zilla. It is the first district in the country to be declared so. As many as two lakh (200,000) farmers in Dang district practise natural farming. Chemicals are banned there. The state government gives farmers, who have native cattle, Rs 900 a month for its upkeep. The state also extends a lot of help to natural farmers to encourage them to continue natural farming.

In Andhra Pradesh, Vijay Kumar, a former chief secretary closely associated with the move to push the state into natural farming, has brought many farmers into the fold. More than five lakh (500,000) farmers in Andhra Pradesh are practising natural farming now. Where once the soil was non productive, the farmers are now growing three crops on it.

Even if a farmer has a single desi cow, he or she has enough manure to fertilise an acre of land.

All this has health benefits too

In conclusion, I would like to believe that switching to natural farming can reduce the incidence of cancer. Look at Punjab that is agriculture intensive and uses maximum chemical fertilisers and pesticides. There is a train from Bhatinda to Bikaner in Rajasthan that has come to be known as the ‘cancer train’ as a large percentage of its passengers suffer from cancer, and go to Bikaner for treatment.

We are creating a network of farmers who practise natural farming, not just in Gujarat, but now also in Uttar Pradesh.