Bhusara (Muzaffarpur), Bihar

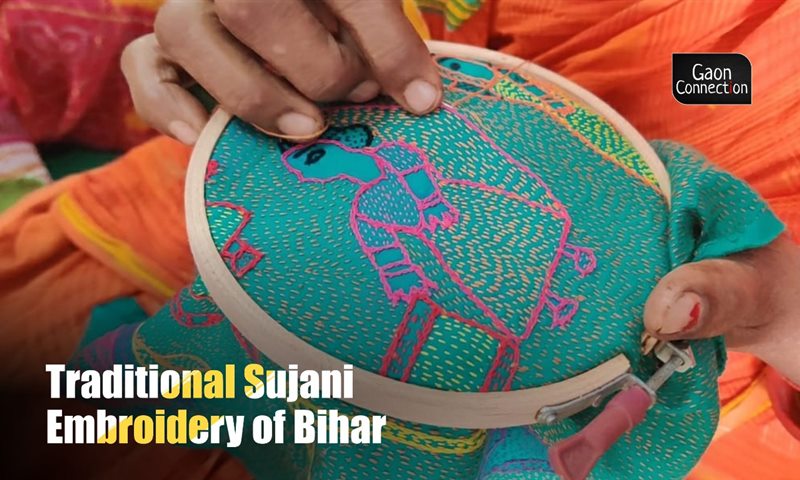

It is needlework that originated in necessity. Where patches from old saris, dhotis and outgrown clothes were joined together to make swaddling cloths for newborn babies. The well worn, soft and comforting old fabrics were perfect to wrap the little one in. Sujani embroidery (su means facilitating and jani means birth), as it is known, enhanced the labour of love even more.

Sanju Devi sat on a bright orange mat, surrounded by pieces of cloth, head bent and focussed on her needle and thread. The 45-year-old is director, Sujani Mahila Jeevan Foundation, formerly known as Mahila Vikas Sahyog Samithi, at Bhusara village, in Bihar’s Muzaffarnagar district, about 85 kilometres away from the state capital of Patna.

The Foundation nurtures and promotes the traditional sujani embroidery, which is prevalent in north Bihar, and this craft practised by the rural women got a GI (geographical indication) tag in 2006. GI is a sign used on products – handicrafts, agricultural produce, etc – that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities that are due to that origin.

“There are about 600 women in and around Bhusara who do the sujani embroidery,” Sanju Devi told Gaon Connection. In 2014, Sanju Devi got the ‘World Craft Council Award of Excellence’ from UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), for handicraft.

Also Read: For many women artisans, traditional embroidery is a passport to self-empowerment

Sujani work that was common to village households as they created swaddling for newborn babies, has now been extended to making other products such as cushion covers, letter holders, embroidered patches to embellish kurtas, sarees, etc. The embroidered products are usually sold in art and craft melas and exhibitions.

Along with Sanju Devi, several other women wield their needle and colourful threads over motifs traced onto the cloth, and using chain stitch and a straight running stitch, create works of art. Layers of soft cloth are stitched together using simple chain stitch and running stitch to make baby quilts, and now other products.

The tradition of sujani

Traditionally, the embroidery that the mother of the baby or women of the household did on the sujani was representative of the dreams and hopes they had for the new baby.

“In fact sujani is considered a cousin of Mithila painting,” Ashok Kumar Sinha, director, Upendra Maharathi Shilp Anusandhan Sansthan, in Patna that promotes craft in the state, told Gaon Connection. It also resembles the kantha work of West Bengal, he pointed out. Kantha also emerged from making baby quilts out of old discarded fabric.

Also Read: To beat the lockdown blues, traditional artisans of Kachchh in Gujarat go online

Initially there were three women from Bhusara village, but now there are 600 women from more than 20 villages who practise the craft, under the umbrella of Sujani Mahila Jeevan Foundation.

“The work would have remained within our four walls, had not Viji Srinivasan of ADITHI, and Nirmala Devi of the Sujani Mahila Jeevan Foundation, revived it in Bhusara village in the eighties,” Sanju Devi, said. Srinivasan (who died in 2005) from a non-profit called ADITHI along with a group of women from Bhusura village in Muzaffarpur district of Bihar, in 1988, began the revival of sujani embroidery. The non-profit works with rural women to empower them and provide them a source of livelihood.

One of the first to join ADITHI from Bhusara village was 68-year-old Nirmala Devi. “In 1988, we were only three women who were trained by Viji Srinivasan. But gradually, a little bit of money began trickling in, not more than twenty rupees a day,” recalled Nirmala Devi. But, she said ever since, sujani embroidery got a place in the sun and it began to be noticed and appreciated even outside their village.

“I worked with Chennai-based activist Viji Srinivasan,” Asita Maldahiyar, of ADITHI, told Gaon Connection. ADITHI took the initiative to popularise sujani and take it outside the boundaries of the state, Maldahiyar, who is based in Patna, added.

Also Read: The whisper of the world-famous Banka silk from Bihar is being silenced

Social and financial empowerment

The embroidery has given the women a sense of purpose and independence. “We do not have to depend on anyone. Now we are self-reliant and can step out of our homes with confidence,” Lakshmi Devi from the Bhusara declared to Gaon Connection.

“I love being a part of Sujani Mahila Jeevan Foundation,” Saraswati Devi, told Gaon Connection. “We have developed a sense of community, and we have an income as well. Doing embroidery along with others is much better than working as a daily wage labourer,” 52-year-old Saraswati Devi said.

According to Sanju Devi, their products were exhibited and sold in several fairs in Muzaffarpur, Patna and in Delhi. The women have also worked on pieces commissioned by students and designers from National Institute of Fashion Technology, Delhi.

In 2014, textile and fashion designer Swati Kalsi had organised a workshop for the Sujani embroiderers at Delhi, Sanju Devi told Gaon Connection. But, there are no structured marketing systems in place, she said.

“Our income is not fixed. There are times we earn anything upto five thousand rupees a month, but then again there are days we earn nothing. It’s my dream that one day our embroidery will earn worldwide appreciation,” 25-year-old Rani said.

While the motifs for sujani were traditionally inspired by nature with clouds, birds, fishes, fertility symbols and so on being embroidered on the colourful pieces of fabric, it has taken on another dimension now, with more contemporary social issues, both the good and the bad becoming the subject matter of the embroidery.

“With the transformation of society, motifs have changed with the course of time. Now the work represents the evils of society, the problems women face, such as child marriage, domestic violence and the tradition of ghungat (where women are expected to cover their heads and faces with a veil),” said Rani.

But the pandemic has applied the brakes on their work, like it has with any other profession. “We are at home doing nothing but hope that after the third wave, we will get work,” said Nirmala Devi.

Training so many women in a small congested space in her home is not possible on account of the pandemic and Nirmala Devi said there were efforts to see if they could get a bigger space to do the work.

According to Ashok Kumar Sinha, director Upendra Maharathi Shilp Anusandhan Sansthan, the infrastructure at Muzaffarpur district still awaits approval. “It is probably held up on account of the pandemic,” he told Gaon Connection.