Manjunath Kariyappanavar, like many of his counterparts who were living away from their native villages, was straddling life between his studies and work in Gadak, Karnataka, before the nationwide lockdown was announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on March 24, 2020. He lost his livelihood, returned to his village in Bagalkote, and worked as a daily wager under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (MGNREGA), to support his family of four.

“After a few days, the MGNREGA work stopped and I, again, had no means of earning an income. It was extremely difficult. Now, I am assisting an electrician and earning some money to feed my family. My brother is sitting idle at home as there is no work under MGNREGA or elsewhere,” Kariyappanavar told Gaon Connection.

Kariyappanavar’s story mirrors the experience of several workers across the country who failed to find work, or found limited days of work, under MGNREGA, during the lockdown. This 2005 Act aims to enhance the livelihood security of rural people by guaranteeing them – adults wanting to do unskilled manual works – 100 days of wage-employment a year.

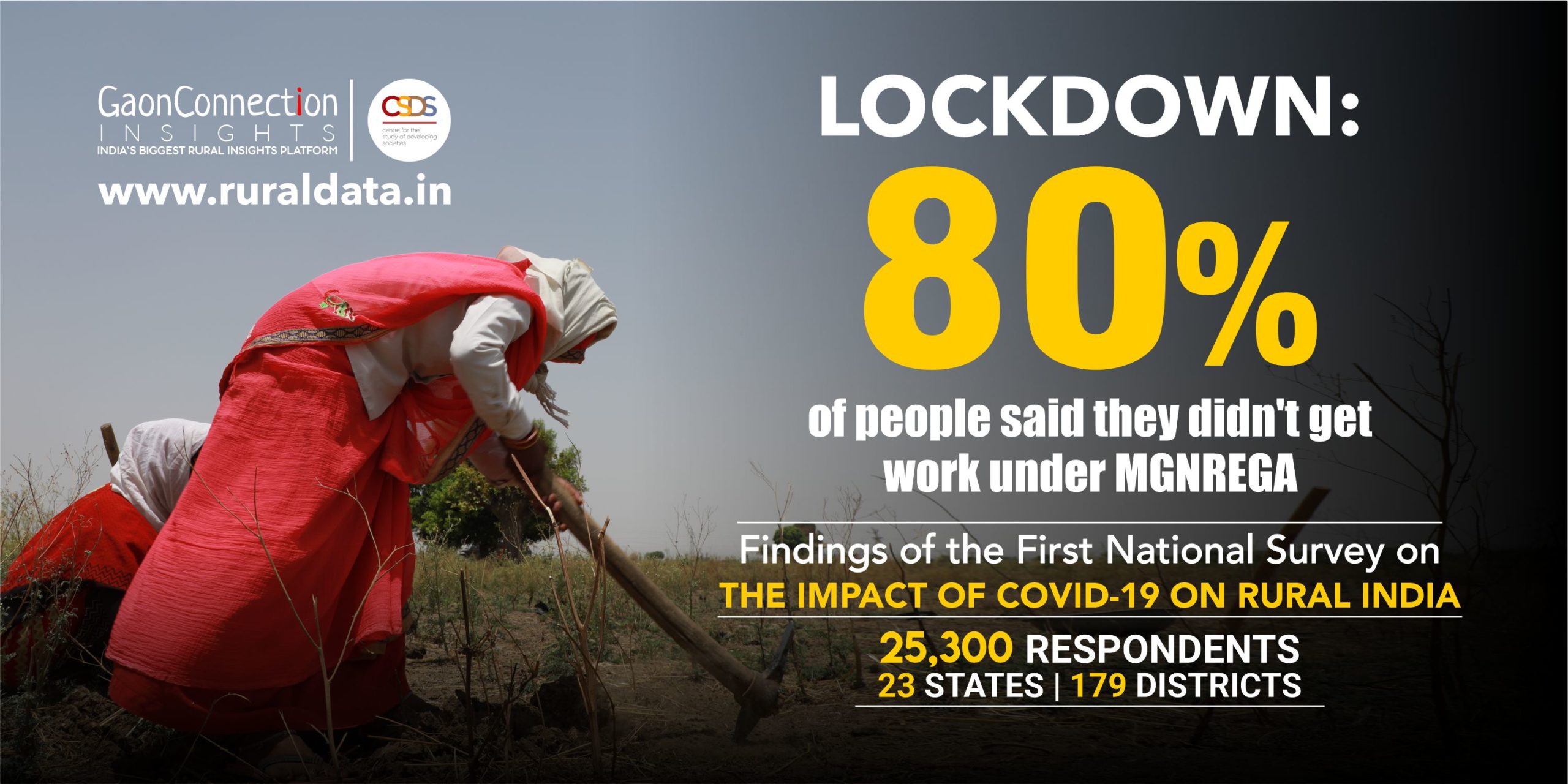

In a first-of-its-kind national rural survey with 25,300 respondents, carried out in 179 districts across 20 states and three union territories by Gaon Connection Insights, the data and insights arm of India’s largest rural media platform, eight out of 10 rural respondents said they failed to find work under MGNREGA. The survey also found that the poorest households were least likely to have benefitted from MGNREGA during the lockdown. For instance, only 17 per cent of the poorest households reportedly got work under MGNREGA during the lockdown, whereas 24 per cent rich households found wage-employment under the rural employment scheme.

Further, the state-wise data shows that well over half the households in Chhattisgarh (70 per cent), Uttarakhand (65 per cent) and Rajasthan (59 per cent) reported of a household member getting MGNREGA work during the lockdown. In sharp contrast, only Jharkhand (9 per cent), Maharashtra (8 per cent), Punjab (7 per cent), Himachal Pradesh (7 per cent), UTs of Jammu & Kashmir-Ladakh (4 per cent), and Gujarat (2 per cent) found employment.

The implementation of the nationwide lockdown from March 25, 2020, affected the work of all sections of the society as most economic activities came to a standstill. Poor families suffered the maximum brunt.

Gaon Connection’s recent survey reveals over two-third (71 per cent) respondents – the main earners of their respective households – reported a drop in the monthly household income during the lockdown months compared to the pre-lockdown period. The survey also found that poor and lower-class households reported the greatest drop in household income and the greatest rise in hardship during the lockdown. Even middle class and rich households bore the brunt and the majority witnessed a drop in income, but they weren’t as adversely affected.

Take the case of Allahuddin, a resident of Ballari district of Karnataka, who used to earn Rs 500-600 per day before the lockdown. But, he was asked to leave by his employer when the lockdown was announced. Now, he is working as a labourer and earning Rs 275 per day wage under MGNREGA. But, he is unwilling to go back to the city to work. “The number of corona cases in the city are on a rise, I don’t wish to risk my health and my life. Despite all the shortcomings, including working on lower wages than what I was earning in the city, I’d prefer to continue to work in the village,” he told Gaon Connection.

The reluctance to go back to the city, especially due to the rise in the number of corona cases, is a popular sentiment being reiterated by the workers. However, they find themselves in the middle of a dual quandary – being unable to find employment under MGNREGA, and risking their health and lives by moving back to the city for work.

The Gaon Connection Survey has made some interesting findings. In the three purely Congress-ruled states where the survey was conducted, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Punjab, Rajasthan (59 per cent) and Chhattisgarh (70 per cent) stood out as a very high proportion of households in these two states reported having done MGNREGA work during the lockdown. The BJP-ruled states, on the whole, did not perform as well as the Congress-ruled states on the MGNREGA front. However, there were some exceptions such as Uttarakhand (65 per cent).

For the few who have been successful in finding employment under MGNREGA, the most common demand is to increase the number of minimum days of employment guarantee from 100 days to 200 days due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2005 Act allows for increasing the number of days of work from 100 days to 150 days a year during a disaster/drought.

“I have no idea what I am supposed to do after the completion of 100 days under MGNREGA,” said Abdul Rahman, a MGNREGA worker. “It would be of great help if the minimum number of days get extended by at least 50 more days,” he added.

The Karnataka government has already written to the Prime Minister’s Office requesting to extend the minimum number of days under MGNREGA by 50 days this year. The letter issued by L.K.Atheeq, Principal Secretary to Karnataka Government, in the month of May, claims, “10 lakh workers are being employed under the scheme across the state and 1.03 lakh fresh works are under implementation,” and has requested to increase the number of days to 150 citing “High demand from the workers.”

However, due to the unprecedented crisis posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, several states including Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu are demanding to provide for an additional 100 days, thus raising the provision for the total number of employment days to 200 days in this financial year.

An analysis of person-days work generated under MGNREGA for the financial years 2019 and 2020 shows that there has been a steep rise in the number of person-days generated this year as compared to the last year.

Between April to July this year, 1,656 million person-days were generated across the country, whereas in 2019, 1312.1 million person-days were generated under MGNREGA.

However, this rise was not witnessed in the month of April 2020, when the first phase of lockdown was in place, but in the months subsequent to it. April 2020 generated 141.4 million person-days in comparison to 270 million person-days generated in April 2019. There has been an upward trend in the months of May and June this year, which generated 560 million and 640 million person-days, respectively, when the state governments initiated the process of easing lockdown restrictions, calling it ‘Unlock’.

Nikhil Dey, social activist and founder of Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan, states that the solution to this problem lies in an urban employment guarantee.

“People are not going back to the cities partly because of coronavirus and partly because the work is yet to resume… An urban employment guarantee scheme, like MGNREGA, will ensure they have a fall back in the city for the days they don’t find work in the urban centres,” said Dey.

In order to respond to the COVID-19 crisis, the Indian government raised the allocation for MGNREGA to Rs 1,00,000 crore for the financial year 2020-21. As per recent news reports, the government has already exhausted 50 per cent (Rs 48,759 crore) of the total.

According to Dey, the money allocated to MGNREGA is insufficient keeping in view the surging unemployment crisis due to COVID-19. “MGNREGA is supposed to be demand-based so depending whatever the demand for work be, the government has to meet it. By law, it shouldn’t be budget-constrained,” he said.

More than half the annual budget has already been spent, and about 80 per cent of the rural development budget has also been spent which is dovetailed with MGNREGA, he added.

According to Dey, the situation is worrisome. “Last year this time, Rajasthan had one million people at MGNREGA works. This year, the figure has jumped to 2.2 million, which is more than double of last year,” he said. “Last month, in July 2020, the state had five million people working under MGNREGA. Only 10 per cent funds are left in the state funds now,” he added.

The central government had announced an allocation of Rs 40,000 crore, but it still hasn’t come through. This is expected to lead to a delay in payment of wages, he warned. “If it weren’t for MGNREGA, people would have starved,” he added.