Marihan (Mirzapur), Uttar Pradesh

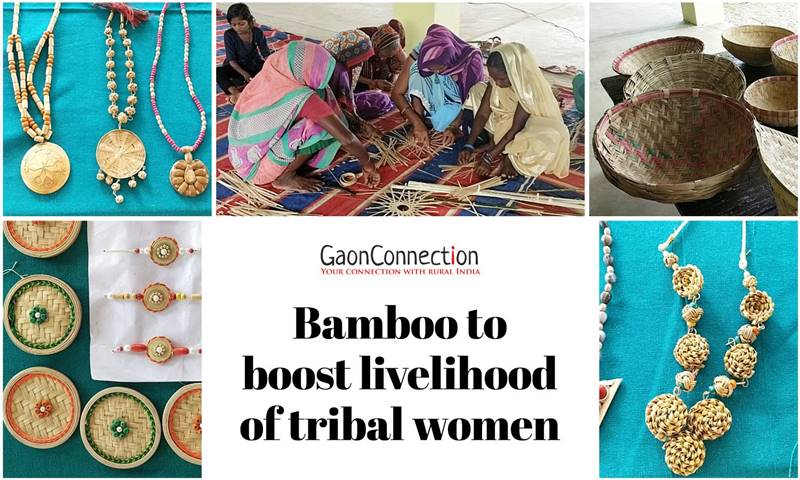

On a bright morning at the Marihan’s common service center, a cool monsoon breeze brushes past the smiling faces of tribal women huddled together on a dhari (flat mattress) and surrounded by pieces of bamboo cut into various shapes and sizes. On a table nearby, jewellery, flower pots, show pieces, mugs and plates, lamp shades are spread out. At first glance it is hard to imagine all these products have been created out of a grass — bamboo — by the women of the Dharkaar tribe, many of whom are illiterate.

Seventy-year-old Ramna Devi, a resident of Bharuhana village of Mirzapur, about 300 kilometres from the state capital Lucknow, has been coming to the common service center at Marihan since August 4 when a training programme was launched by the Mirzapur forest department to train adivasi women in making a variety of items from bamboo, which abound the area.

Ramna Devi is hopeful that her earnings will increase as she now has a wide variety of products to sell in the market as well as to the wholesale traders.

“A single bamboo shaft costs about two hundred rupees. We usually made hand-fans from the fans. A single shaft can be used to make around a hundred fans,” she told Gaon Connection. “Earlier we used to get fifty rupees per fan, but now we have learnt to make mats out of bamboo. It takes longer to make mats but we can sell them at a far greater price than fans,” the confident villager said.

This training camp is a unique initiative of the district forest department to increase the income of local villagers by providing them free training in making products out of bamboo for sale. A number of tribal people in Marihan tehsil of Mirzapur do not own land, or barely have an acre of land, and have no other income source. They either work as agricultural labourers or practice subsistence farming. The COVID19 pandemic has made matters worse.

Also Read: Tribal communities dependent on forest produce seem to have fared better in the pandemic

The 15-day long bamboo handicraft training camp, which kicked off on August 4, will come to an end tomorrow August 18. On an average, 25 tribal villagers participate in the training in a day for which a design consultant, Neera Sharma, has come all the way from Assam in northeast India.

Bamboo-based handicraft training for tribal women

Neera Sharma, a resident of Tezpur district in Assam, is an expert in bamboo-based handicraft and has come all the way from 1,300 kilometres away to train the tribal people. She has been invited by the Uttar Pradesh government to hone the skills of the Dharkaar adivasi community in Mirzapur.

Talking to Gaon Connection, she said: “I basically focus on finding ways in which we all can live our lives in sync with nature. I visit villages across India and try to teach people the skills by which they can improve their living conditions by making use of the natural resources in the area.”

According to Sharma, bamboo is one resource that can help build rural livelihoods. “Bamboo is an excellent opportunity for eco-friendly handicrafts. By utilising the natural resources like bamboo and developing skills to make it lucrative for the markets, the villagers can earn a regular income,” the consultant said. She went on to add that rural women have a good grasping power and they are naturally blessed with a talent for handicrafts.

Also Read: Archery then and now – How tribal communities in Tripura used one of the oldest known weapons

Meera, a 45-year-old trainee at the camp thanked the consultant for the training received and stated that she is hopeful that her profit margins would rise exponentially.

“The training is focused on exploiting the maximum profit from a bamboo shaft as the previous items that we produced hardly amounted to fifty rupees per bamboo product but now, having learnt to make things like bangles, earrings and other small products, we can now earn almost two hundred rupees per item. The quantity of bamboo needed is also lesser as these items are small in size,” she told Gaon Connection.

Village men also join in

Meanwhile, some local men have also joined the handicrafts training programme. Ashok Kumar, a 35-year-old from the Bharuhana village of Mirzapur, is one of the three men present at the training camp which has a majority of women (22 women, 3 men). He told Gaon Connection that the number of items that he can now make from bamboo have nearly tripled and is eager to take his products to the market and earn better profits.

Also Read: 35 needles, black sesame dye and a prayer for the tiger god — the Baiga tribe’s godna art

“Earlier we used to make simple things out of bamboo like a basket, a hand-fan, jhunjhuna (a rattle toy for kids) or a sieve. But now I know how to make jewellery, ornamental products like carved animal figures,

dolls and other things. I am sure these things will get better prices and my income would increase,” said a happy Kumar.

“Free me sikhaya ja raha hai, jab seekh jayenge aur prabhu ki iccha hogi to aage kaaryakram achha rahega,” the 35-year-old trainee added. (The training here is for free, god willing, things will be better in life when I completely learn these things and earn better)

Meanwhile, PS Tripathi, the district forest officer (DFO) told Gaon Connection that the training camp is very popular among the villagers.

“It’s been a successful workshop. They are getting to learn to make so many products that they are more confident about themselves now. The products that they are making will fetch them better prices and their livelihoods will get better,” Tripathi said.

Camp organised under National Bamboo Mission

The training camp at Mirzapur has been organised with support from the Union Agriculture Ministry’s National Bamboo Mission which was launched by the central government in 2006.

However, the mission was restructured in 2o19 to include initiatives so as to enable the local artisans to utilise bamboo and get better prices for their products.

The restructuring was accompanied by an amendment of the Indian Forest Act in 2017, which removed bamboo from the definition of trees, hence bamboo grown outside forests no longer needed felling and transit permissions.

Also Read: Villagers in Bangladesh build ‘jungla dams’ using wood and bamboo to prevent land erosion