Kolkata, West Bengal.

Forty-year-old Surojit Saha and his wife Sinjinee Saha own ‘Swasti..’, an invitation card shop on Amherst Street in Kolkata, the capital of West Bengal. The ‘ka’ in the name fell off during Cyclone Amphan in May this year, and they are waiting for the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic to end so that the ‘Swasti’ can go back to being ‘Swastika’. “Anyway, there is no customer to point out the missing letters nor money to fix it. Let it be,” Surojit told Gaon Connection.

Swastika is a small shop that faces the arterial Mahatma Gandhi Road in the city. Like it, there are at least 150 shops, both retail and wholesale, between Sealdah Station and College Square, all of which were shut for almost half a year due to the pandemic. They have only now resumed work. There has been a steep fall in the sale of cards due to the pandemic; few customers are booking cards for the December wedding season, said Surojit.

India’s wedding market is estimated to be US$ 50 billion and was growing rapidly every year till COVID-19 slowed it down. It is estimated that 10 million marriages are held in the country every year and the market for cards is estimated between Rs 8,000 crore and Rs 10,000 crore. But now, from hundreds and thousands of guests, weddings in the pandemic have come down to a small family affair.

On August 29, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs – under Unlock 4.0, allowed an increase in the number of people allowed for a social, cultural or religious gathering from 50 to 100, in areas outside containment zones. The new guidelines came into effect on September 1.

This has provided a ray of hope to the wedding invite market of Kolkata, which is one of the biggest markets for invitation cards in the east and north-east part of India.

The nationwide lockdown began on March 25, pausing businesses across sectors. The wedding industry was one of the worst affected, as the lockdown extended into the ‘lucrative’ wedding season — which extends from March to June. In the wedding industry, the invitation card market can be considered the tip of the iceberg.

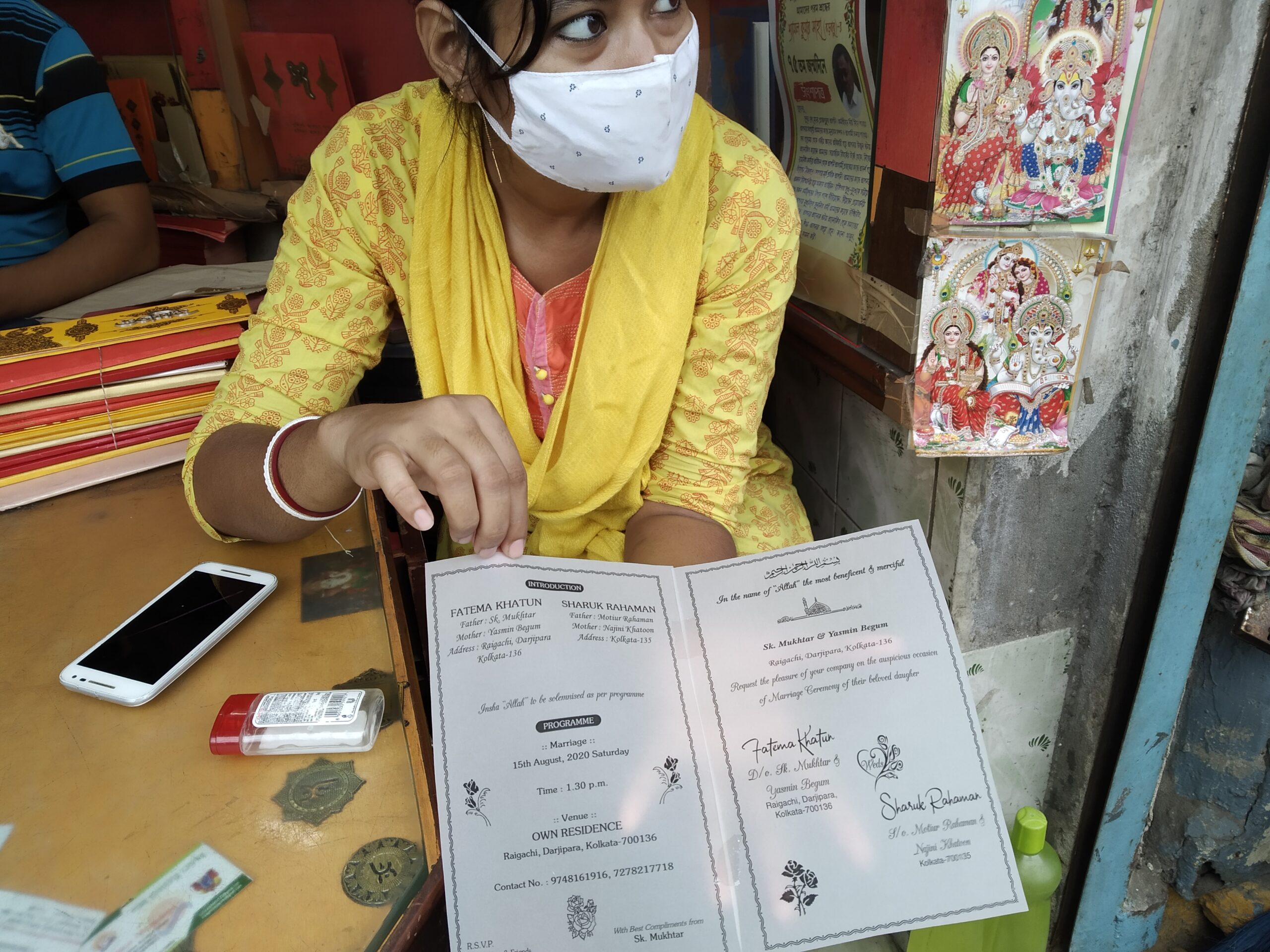

The shop owners continue to lose business and suffer monetary losses, but the fear is palpable on the faces of workers in the sector, who fear job losses. Since the guest count for functions during the pandemic has been brought down to 100, from thousands in some cases, sending digital cards or PDFs of cards over WhatsApp has become the new norm. E-invites are being seen as a safe and economic alternative during the pandemic.

According to Sinjinee, most customers coming to the shop to place orders for invitation cards have been ordering just four or five cards — because registry and temple weddings have become more common.

Kolkata’s wedding invite market

Most invitation card shops in Kolkata are over 70 years old, and come with a historical legacy. Like much of the architecture, the history of calligraphy-based invitation cards are rooted in the city’s colonial past and Victorian tradition.

The more glittery, vermillion palettes can be traced back to Rabindranath Tagore’s wedding on December 9, 1883. The card with these colours and designs were decided by Tagore himself. Since then, styling and designing of cards are considered a timeless trend.

Shops selling invitation cards have set up shop in between Sealdah Station and Mahatma Gandhi Road leading to Howrah Station. Another similar market is at Burra Bazar and Old China Bazar. What sets Amherst Street apart is that it is also known as ‘a printing hub’.

“Every season, a new style sheet is created. The changes relate to font design, colour and prints,” said Bodolochan Maiti, who owns a digital printing outlet on Patwa Tala lane, Amherst Street. “Around 35 digital print shops have set up shop in the area,” said Malay Kumar Paul, a senior sales manager from Konica Minolta, a Japanese printer manufacturing company.

Before the lockdown, most invitation card shops had a cap on the minimum order to be placed — on average, it was between 100 and 150 cards. Right now, they are even willing to print a single card.

Shopkeepers are also being very careful while taking orders; they avoid bulk orders even if it means more money. The reason? People who had ordered cards before the COVID-19 never came to collect them.

“Even after the declaration of Janata Curfew on March 22, no customer came to settle accounts or collect the cards ordered,” said 70-year-old Kagesh Chandra Dey, who owns an invitation card shop on Amherst Street.

Dey re-opened his shop two months ago in July and is still waiting for customers to pick up their order from the heap of ready-to-deliver cards made from different materials — from cloth to expensive paper ordered from Tripura (Agartala), Assam and within Kolkata too.

“Today, you can see a few shops open on either side of the road. A week ago, it was just two or three shops, including mine,” said Sushanta Mukherjee, who sells stationery and lottery tickets. Before COVID-19 struck, and pushed the market into a slump, Mukherjee would witness crazy crowds on the pavement every wedding season. Shops were full of customers desperate to catch the eye of the owner or staff. This year, the silence is deathly.

Printing problems

The cost of screen printing is lesser than digital; it is also labour-intensive and provides more employment. However, according to 40-year-old Rajiv Banerjee, who owns a printing shop on Patwa Tala lane, it’s not just COVID-19 that has destroyed their business.

“Traditional printing has been closely competing with technology for the past two years. I knew that six years later, my business might wind up, and was prepared. Corona has hastened that end. In the last four months, I’ve lost about six lakh rupees,” he said.

Sanjay Printers is one of the many screen printing shops in the narrow lane, opposite to EBAD Construction with a missing ‘E’. The grille gate is locked from inside. It has been this way for the last six months, informed 60-year-old Lakhi Das from inside the shop. “The owner Sanjay lives in Howrah, and has closed the shop because there is no business at all. All the card shops are closed,” Das told customers enquiring about the owner.

There are two other stores with locks on their front gate, and two more fear closure due to lack of working capital. These sectors are closed or heading towards that due to lack of card sales. Since printing orders depend on card orders, outlets whose sole business is printing are directly affected. “Printing doesn’t exist independently; it’s a process that includes binding, designing and packaging,” Banerjee elaborated.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased use of technology to distribute invites, as people follow physical distancing and avoid touching things and surfaces. “E-invitations are fast and safe. They are also less expensive and more eco-friendly,” Shivani Agarwal, a law student based in Noida told Gaon Connection.

Many owners of invitation card shops fear that the majority feels like Agarwal, and they dread a tech takeover. However, Dey, with the wisdom of his 70 years, feels otherwise. WhatsApp and e-invites may turn out to be a new trend, he admitted, but to say that technology will take over the business is misleading, he added. “People will have to print cards because that is a part of tradition. Moreover, it’s a status symbol,” he explained.

Dey is a picture of positivity. Business will resume in mid-November and continue to bloom till February, he insisted. “This is the peak season for weddings and social events, and our business will be back,” he said.