Dusk is approaching. And Aparna Sarkar, an ASHA (accredited social health activist) worker, is in a hurry. Draped in a light blue saree with a leaf motif, and wearing the symbolic red-and-white bangles on her wrists, and a thick streak of sindoor (vermillion) on her hair parting, Sarkar picks up a large bell and steps out.

She will be walking around Khairapali village in Mathili block of Malkangiri district in Odisha, ringing the bell till 8 pm to remind the villagers to set up their new mosquito nets — officially known as long-lasting insecticidal nets, or LLINs — distributed to them last year.

The net fabric is pre-treated with an insecticide and remains effective for three years. Sleeping inside these nets means protection from mosquitoes and vector-borne diseases such as malaria, which is a serious public health concern in the district.

Malkangiri, a predominantly tribal district, affected by Naxalism and infamous for poverty and malnutrition, is a hotbed of malaria. Odisha carries more than 40 per cent of India’s total malaria burden. Malkangiri, a very high-risk district, reports about half of the total malaria cases in the state.

However, with various interventions, the malaria burden in the district, and also the state, has come down. The district administration is leaving no stone unturned in its war against malaria, which killed 7,700 people in the country in 2019.

WhatsApp groups, IEC (information, education and communication) materials, mic announcements, training of frontline health workers, active participation of local teachers and schools, mass screening, patient cards, sanitation drives, behaviour change and promoting the use of LLINs are some of the measures undertaken.

“In January 2020, Malkangiri district had a malaria case load of 1,272. But, this January, the district has reported only 235 cases, a decline of 81 per cent,” Dhaneshwar Mohapatra, head of malaria division, and additional district public health officer, Malkangiri, told Gaon Connection.

ASHA workers like Sarkar form the backbone of the eastern state’s malaria eradication programme. Also, based on inter-departmental convergence, 14 line departments in the district are now working in tandem to make Malkangiri malaria-free.

Malaria-free Malkangiri Campaign

Making Malkangiri malaria-free is a daunting task. Malaria is endemic to the district whose 57.83 per cent population is tribal/indigenous people. Several ecological conditions, such as hilly areas, stagnated water, high humid temperature and an annual rainfall of 1,700 millimeter, enable mosquitoes to breed. The district reports high malnutrition in children. As per the National Family Health Survey-4 of 2015-16, slightly more than half of under-five kids in the district were underweight. More than 47 per cent under-five kids were stunted (height-for-age).

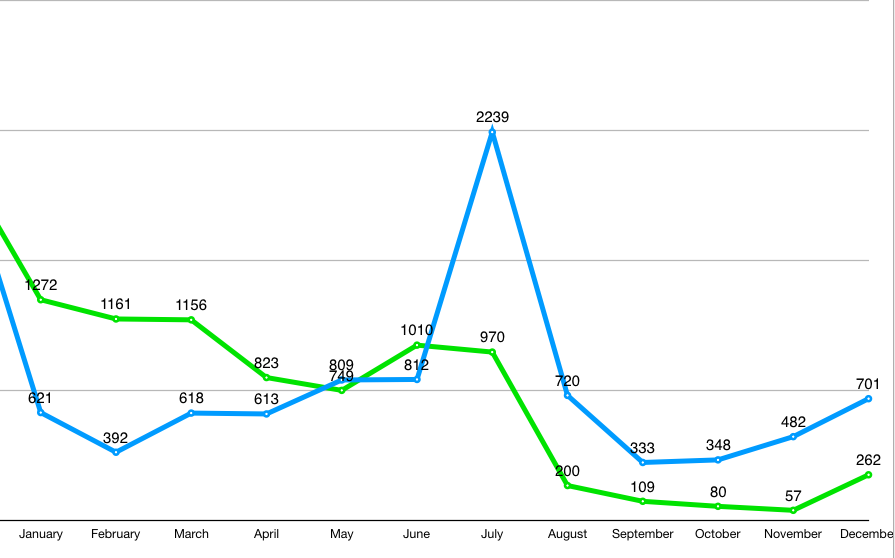

Till June last year, the district was reporting a very high case load of malaria. The number of cases in January last year was 1,272, a steep jump from 621 in January 2019. A rising trend was observed till June 2020 (see graph).

Graph: Malaria case load in Malkangiri, Odisha: 2019 (blue line) vs 2020 (green line)

The district administration was intrigued by the surge in malaria cases. “In December 2019, we received the long-lasting insecticidal nets from the Central government. We distributed four lakh and twenty nine thousand nets among villagers in January, February and March 2020. However, the malaria case load continued to show a rising trend,” said Mohapatra.

In April and May last year, amid the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, a survey was conducted to know how many rural households in the district were using the new pre-treated nets. Panchayat members and local teachers were roped in for the door-to-door survey.

The survey showed only 30 per cent of the households given the new nets were actually using them at night, informed Mohapatra.

On June 11 last year, Manish Agarwal, the then collector of Malkangiri, initiated the process for the interdepartmental convergence to launch the Malaria-free Malkangiri Campaign. It was decided that officials and workers from all 14 line departments will work together to control and eradicate malaria. This campaign has borne fruits and has now emerged as the Malkangiri model.

Monitoring, surveillance & reporting

The Malkangiri model is based on three tier interdepartmental convergence — district, block and panchayat — strengthened by a transparent monitoring, surveillance and reporting system. For instance, 70 forest guards attached with the forest department and 100 forest committees have also been roped in to raise awareness about malaria control and use of the pre-treated nets in forest villages.

Malkangiri district has a total of seven blocks, and the district administration has purchased 30 microphones (mics), one for each sub-centre to hold mass awareness programmes on malaria. The plan is to ensure one mic per village in the coming years (the district has 192 villages as per Census 2011).

Role of ASHA workers

Frontline health workers are the backbone of Malkangiri’s anti-malaria programme. They undertake daily house visits entailing health related updates, night supervision, bell ringing, announcements over the mic and awareness regarding use of new nets.

ASHAs of Malkangiri district have proven their dedication towards wiping off #Malaria from their district through this unique move – each ASHA residence has been declared as Malaria Treatment Center where blood collection for testing Malaria is being done. #Health4All pic.twitter.com/shZhBZLVVW

— H & FW Dept Odisha (@HFWOdisha) September 7, 2018

“Our main job is to raise awareness about malaria, its symptoms, and the precautions to be followed by villagers. Initially, we held meetings with village-level self-help groups to educate them about malaria and the importance of using the nets,” Sarkar told Gaon Connection.

“Apart from this, each ASHA worker daily visits at least 10 households to screen people for malaria. We check if the family is using their nets. We have made patient cards with all health details,” she informed. “We also carry rapid malaria testing kits with us, which can confirm malaria infection within 20 minutes,” she added.

The daily house visits have not only raised awareness about malaria among people, but have also helped frontline workers get acquainted with real-time incidence of malaria and the extent of precautionary measures adopted at the household levels.

Each block of Malkangiri has formed its own WhatsApp group on which ASHA and anganwadi workers share information every day about their home visits and patient records. Photographs are also shared.

If a person has malaria, he/she is administered medicine in front of the ASHA worker. Thereafter, contact tracing is done in the neighbouring four to five households and fever surveillance done in the entire village.

“The only secret to making Malkangiri malaria-free is hundred per cent usage of LLINs [long-lasting insecticidal nets], and with our sustained campaign, we will make it happen,” said Mohapatra.

“The past year has been extremely challenging because, apart from the malaria awareness programme, we, the ASHA workers, also had to work day and night on COVID-19. But, there is a great sense of achievement when we get to know that malaria cases are on a decline in our villages,” said Sarkar, who tested positive for COVID-19 last July and has now received both the doses (a month apart) of COVID-19 vaccine.