Bhaiyya Lal had a close encounter with the tigress of Sapat, which he survived, but which left him with a fear of the animal so much so he couldn’t even stand to hear the word ‘tiger’ mentioned in his presence. It was a life-threatening experience, that often leads to a phobia. Though he never discussed his fear of tigers, I came to learn about it the hard way during one of my field excursions. The incident that I am going to narrate now cured him of that phobia to a great extent.

It was August of 1987. Plenty of rain had already satiated the land, and the work of reclaiming the habitats for wild animals lost to an exotic weed was on. In the Tikari beat (a beat is an area in the forest that is the smallest unit of management), lantana had spread everywhere, and there was hardly anything for the grass-eaters to graze on. Pench had this shortcoming – it had no natural grassy blanks, and whatever open patches might have existed earlier, were all encroached by the weed – lantana.

In our training, we had heard some experts on wildlife management who spoke against eliminating lantana completely as this exotic from tropical America and Africa has more or less naturalized in this country, and many frugivorous birds now depend on it for berries. Besides, the deer, antelope, small mammals, reptiles and the carnivores use it for resting, breeding, ambush and escape cover. So, our work was based on that principle.

As I had narrated to you in my previous stories about Pench, my staff were greenhorns; they needed supervision and guidance, and therefore my frequent presence in the field became necessary.

That wet August morning, I was in the field to inspect the progress of the weed removal work. With me was my brother-in-law, Hemant, who was visiting a jungle for the first time. As usual Bhaiyya lal was manoeuvring the Mahindra Jeep deftly through the serpentine dirt roads of Karmajhiri. After crossing the nala behind Karmajhiri forest rest-house, we were on the Kumbha Baba road. After about three kilometers we reached the guard’s camp (a thatch hut where the beat guard resided) in the middle of the jungle amidst deer, leopards, and tigers. We stopped there, and I took Hemant with me to the foothill of Khairvan Matta (hill). To make water available to wild animals and birds we had created a small watering point in the valley by channelling water from a spring located on the upper reaches of this hill.

This contraption was an innovation worth the effort. Earlier that small trickle of water from the rock-face used to disappear into the soil without becoming available to animals and birds. The only visible creatures then were the butterflies and bees that hovered over the puddle to suck up the mineral-rich water which they relished. The mineral-rich turbid water from this spring looked like diluted milk. The locals called it Pandry Aier (Safed-Paani). A small earthen bund was built around the seepage point to impound the water gushing out from the rocks at the top of the hill. The impounded water was siphoned down through a PVC pipeline down to the valley where a small cemented trough was built to hold the water for wildlife. As the water ran down uninterrupted, the overflow had created a wallow. This wallow had added value to the habitat as for the sambar, and wild pig this became a favourite spot to take mud baths to their heart’s content.

We wished to watch some of them at the wallow so we inched towards the water hole cautiously and silently, a sambar stag that was busy wallowing in the mud sensed our presence, it stood up, raised its tails and cocked its ears. And next moment, giving a blaring honk sprinted up the slope into the woodland. This uncanny sense of animals keeps them alive in the jungle.

We climbed up the hill to the mouth of the spring, cleaned the leaf litter and walked down towards Tikari to oversee the work in progress. We spent about an hour with the staff. The work had progressed well. The method which we used then was to gird the lantana clumps together with a strong rope and then two to three labourers were deployed to pull the rope to uproot the clumps. We did this work in the rainy season as the soaked soil made the uprooting simple and easy.

After the inspection, we began walking back to Kumbha Baba camp where Bhaiyya Lal was waiting for us. On our way back, just about a hundred metres from the camp, on the soft ground I came across the pug marks of a tiger. They looked fresh. My brother-in-law was enthralled and to impress him more, I decided to mimic tiger’s vocalization, which I had learned some months ago, of course after a yearlong practice, and had tested its effect on a group of my staff at Alikatta, It had worked well.

That incident had turned out to be hilarious – one summer morning I along with the range officer Thankan and three guards and some villagers from the forest village of Alikatta were patrolling the bank of the Pench river that meanders through the central part of the National Park. In those days, that is before the entire area of around seventy-five square kilometres got submerged under the reservoir created by the interstate Totaladoh dam built on the border of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, there were many small water bodies known as Kasa or Doh as well as big and small sand dunes all along the river bed.

This area was a favourite resting spot for tigers. As I approached one of the dunes and looked back, I saw that my team was 50 meters away slogging towards me on the wet sand. This was an ideal place to test my newly acquired skill of making a tiger call, so I vanished behind the sand dune and began vocalising like a tiger, soon I began hearing shouts from my team which was coming closer and closer, then I revealed myself smiling from ear to ear. It was a most comical scene- I saw a huffing and puffing Thankan, who usually was a slow person, running full speed towards the dune followed by some villagers and guards. When they saw me out of harm’s way they slowed down and walked to me panting all the way. They began asking where the tiger went? Then I told him that the fake tiger was standing before them, they all began to smiling too though some of them must have been thoroughly annoyed by my prank.

Coming back to the story at Tikari beat – So, I began mimicking the tiger’s call for a few minutes and then I heard the diesel jeep’s engine roar. I told Hemant that Bhaiyya Lal had heard me and he was coming to pick us up. But I was wrong. We were out of the forest patch and were walking on the murram road to the camp. We could now see the forest guard’s hut, but to my utter surprise Bhaiyya Lal was not driving his jeep towards us but in the opposite direction towards Karmajhiri. I couldn’t understand his motive and shouted to him to come our way. But the noise of the Jeep was too loud for him to hear my shouts.

As the jeep was already gone, we decided to walk the three kilometres to the rest house. We ambled along enjoying the jungle, its smells – both fragrant and musty at different places- listened to the orioles, tree pies, drongos and the long drawn kutroo-kutroo of the brown-headed barbet and occasionally the alarm calls of chital and half an hour later reached the stream behind the rest house. From there we saw the jeep coming towards us. Bhaiyya lal arrived; with him were three watchers with machete and sticks. Then everything began to fall into place, and I could understand the reason why Bhaiyya Lal had suddenly fled the scene. Still, I asked him to explain, and as expected he uttered “Sir, as I was waiting for you in the camp I heard a tiger calling from the Tikari side. As you were on foot, I feared for your life. I didn’t know what to do, so I came here to get help.”

Before the Sapat incident, Bhaiyya Lal was a different man. Had he been the original Bhaiyya Lal he would have rushed with his jeep towards the source of the tiger’s call and wouldn’t have fled to fetch reinforcement. But fear didn’t make Bhaiyya Lal a coward, it made him cautious and brave for he was coming back for me with reinforcement to rescue us. Thanks, Bhaiyya Lal.

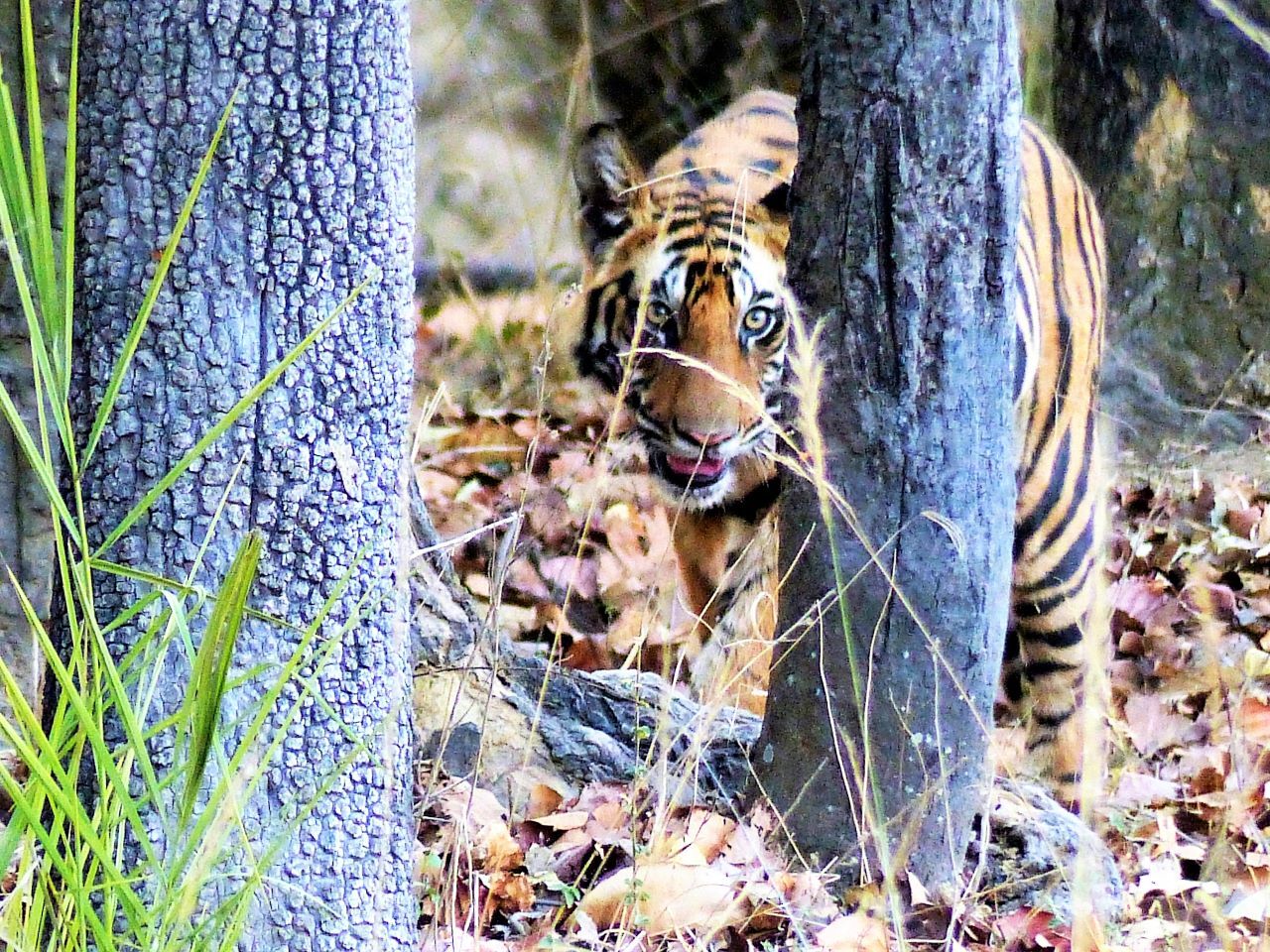

Photo: Suhas Kumar