As you move from Jajpur town towards Sukinda in Jajpur district of Odisha, the fields turn parched and infertile. Rusty, dust-laden leaves wilt silently from dying trees. Trucks pass by, leaving a trail of chromite dust that never seems to settle down. The working classes are busy going to or returning from work; mining ores, lifting weights, occasionally taking long breaths to inhale the air that could kill them.

A board outside the chromite mines owned by TATA Steel, records and displays real time air quality monitoring. It’s difficult to read the figures through the haze but a research study published in May this year found 10-400 parts per million (ppm) total chromium in the air of Sukinda, way above the permissible limits of 0.1 ppm.

The graffiti on the front gate says “Welcome to Swachh Sukinda”. It’s ironic, because in 2007, US-based Blacksmith Institute’s report declared Sukinda as one of the most polluted places in the entire world, alongside Chernobyl in Ukraine. Odisha State Pollution Control Board had dismissed the report, claiming that the overall management is reasonably satisfactory and the situation is not as bleak as was reported. The mining must go on, despite the people.

Chromite mining in Odisha

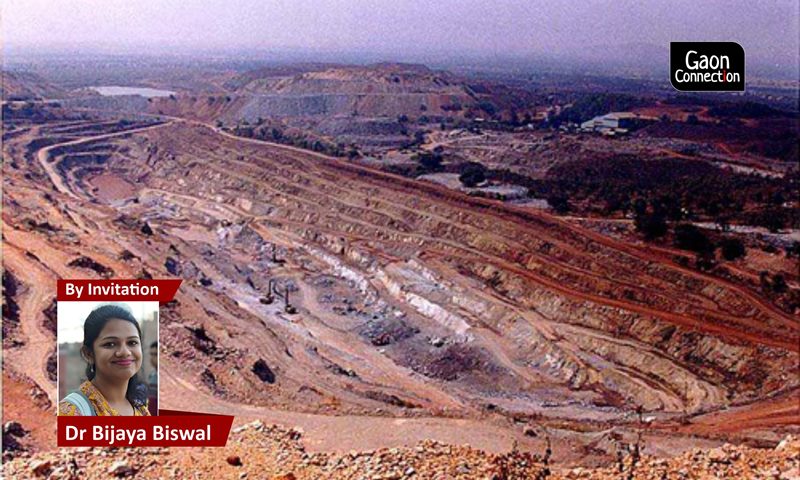

Of the total chromite reserve in India, 98.6 per cent is found in the Sukinda region of Odisha. The area has around 12-14 mines currently in operation which includes government owned Odisha Mining Corporation (OMC), TATA owned Sukinda Chromite Mines, IMFA (Indian Metal and Ferro Alloys Limited), etc.

These mines use the opencast mining methods for extraction of chromite ore which generates huge volumes of seepage water. The water seeps into the ground of the quarry, dissolving the chromium to produce hexavalent chromium, contaminating the groundwater table.

Also Read: Powder keg in Karnataka: The Chikkaballapur and Shivamogga gelatin blasts tip of the iceberg

This leaching of heavy metals and the effluent discharge from mines after ore-washing inevitably finds its way into the stream water of Damsala Nalla, the principal drainage channel of the valley which serves as the surface water source for 2.6 million people in 75 villages.

People of the valley, primarily local tribes like Sabara, Munda, Santhals, Juanga, depend on this water for drinking, washing and agriculture. Chromium hexavalent is not only more easily absorbed by the body but is also carcinogenic, teratogenic and has been recognised as a priority pollutant.

Poison in water and disease burden

Surface water and groundwater in the Sukinda region contain peak hexavalent chromium levels of 2.5 ppm, which is 50 times higher than the permissible limits of 0.05 ppm.

Just to put into perspective, in the well-known Hinkley Groundwater Contamination Case of California, investigated by legal clerk Erin Brockovich (made into a Hollywood movie with Julia Roberts as Brockovich), peak hexavalent chromium level was 0.02 ppm and average levels were 0.001 ppm.

Also Read: The Bloody World of India’s Illegal Sand Mining: At least 193 killed since Jan 2019

The 2018 Annual Report of ICAR-Indian Institute of Water Management shows 70 per cent of water and 28 per cent of soil in Sukinda were found to be unsuitable for agricultural purposes due to the high toxicity level.

Drinking hexavalent chromium on a daily basis would mean a range of diseases such as gastro-intestinal bleeding, ulcers, allergies, brain damage, premature deaths and liver/kidney ailments.

A survey conducted between 1994-1997 by Odisha Voluntary Health Association had reported that annually 84.75 per cent of deaths in the mining areas and 86.42 per cent of deaths in the nearby villages occurred due to chromite mine-related diseases. It also discovered that villages less than one km from the mining sites were the worst affected, with almost 25 per cent of the inhabitants suffering from pollution-induced diseases. It is common to come across anecdotes among locals about a relative they lost because of rectal (gastro-intestinal) bleeding.

A number of more recent research studies confirm how people in mining areas have a much higher disease burden than the general population of India. In Sukinda, this disease burden is further aggravated because of the perpetually low nutrition status among local people, which was highlighted in 2017 by the malnutrition deaths among Juangs residing in the Nagada village.

Rich Lands, Poor People

Since independence, the annual production of minerals in Odisha has increased more than sixty-fold, yet 46 per cent of families in the state live below the poverty line, earning less than Rs 15,100 in a year. Seventy three per cent of Adivasis and 53 per cent of Dalits in the state live below the poverty line.

The National Mineral Policy 2019 defines minerals as shared inheritance by citizens of a state and mentions that the government is only a trustee on behalf of the people. This means, governments don’t own mines. Exploration companies (PSUs or private) don’t own mines. People own mines. Why then, are the Adivasis turned into starving, diseased, daily wage labourers on the mines discovered under their very own lands?

The Mines and Minerals Amendment Act in 2015, directed that a District Mineral Foundation (DMF) be formed in every state that will act as a welfare fund, to be used for development of people and regions affected by mining operation. It mentioned that the high priority areas of spending will be drinking water supply, healthcare, environmental protection, education, welfare of women and children among others.

Also Read: The dark secret of Jharkhand’s shiny mineral mica

The collection of the fund would be 10 per cent of royalty from auctioned mines (leases granted on or after 12.01.2015) and 30 per cent of royalty from mines allocated prior to 12.01.2015.

Odisha has collected the highest amount in the entire country in its District Mineral Foundation, almost 12 billion rupees. However, the areas of spending of DMF are extremely problematic.

Misuse of DMF

The Odisha Cabinet recently approved Rs 266 crores to be taken from DMF Sundergarh for the construction of an international hockey stadium in Rourkela ahead of the Men’s Hockey World Cup in 2023. A recreational facility that would cost Rs 30.42 crore (funded from the DMF) and would have a musical fountain, amphitheatre, jogging track, children’s play area, gazebo, cluster sitting, etc, is being built in Sundergarh as well.

Also Read: Jharkhand has Rs 4,718 crore fund for mining-affected communities. But more than half is unspent

Previously, in the Jharsuguda district, the district administration sanctioned works related to the power supply for the Jharsuguda airport from the DMF funds. Sundargarh district administration has also purchased 25 police patrolling vehicles and constructed boundary walls of the circuit house using DMF in the past.

DMF fund of Keonjhar district was utilised to create a patient facilitation centre in Cuttack, handball stadiums and playgrounds. In Sukinda, they are using Rs 10 crores to grow guava trees over 500 acres of land even as a proper road remains to be built for the connectivity of Nagada village, where the hunger deaths happened in 2017.

The expenditure from another fund that should be ideally utilised to improve the conditions of local people in Sukinda, namely the Odisha Mineral Bearing Areas Development Corporation (OMBADC), also remains questionable.

OMBADC was formed as a Section 25 company in 2014 as per the directive of Supreme Court for “undertaking specific tribal welfare and area development works so as to ensure inclusive growth of the mineral bearing areas” but according to information gathered by RTI Activist Pradip Pradhan, only one per cent of total fund has been utilised for development of tribal people in the mineral bearing districts within four years. The remaining 99 per cent of the amount has been withdrawn and invested without legislative sanction.

Also Read: Conflict in Odisha’s forests leaves both elephants and humans in grief

TATA Steel’s township and steel plant “Kalinganagar ” has been built on the blood and soil of Adivasis in Sukinda, with the backing of the state government. The trauma and wounds caused by the ruthless shooting of 13 protestors in January 2006 by the state machinery while protesting against the acquisition of their land for the plant, are not only open and bleeding, but were recently dug up again when the government accepted the enquiry commission’s stand on the issue, justifying the shooting.

“In my considered opinion, there was no option for the Executive Magistrate than to pass orders for opening of live firing on the riotous mob when all deterrent measures i.e. firing of Tear Gas shells, Stinger shells, Stun shells and then firing of Rubber 88 bullets and the firing to air failed to scare away and disperse the mob,” the original report said.

Neoliberalism is well understood in the context of mining backed up by governments. “Our wealth has always generated our poverty by nourishing the prosperity of others,” wrote Eduardo Galeano in Open Veins of Latin America, “In the colonial and neocolonial alchemy, gold changes into scrap metal and food into poison.”

While one ponders upon these sentences in the context of Sukinda, Tata Steel is launching a Green School Project to ‘teach’ the malnourished children of Sukinda about sustainability and environmental degradation, even as chromium flows in their water bodies and inside their tiny bodies in their veins.

Bijaya Biswal is a medical doctor and public health researcher, currently exploring the causes and implications of health inequity across Odisha. Views are personal.