Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

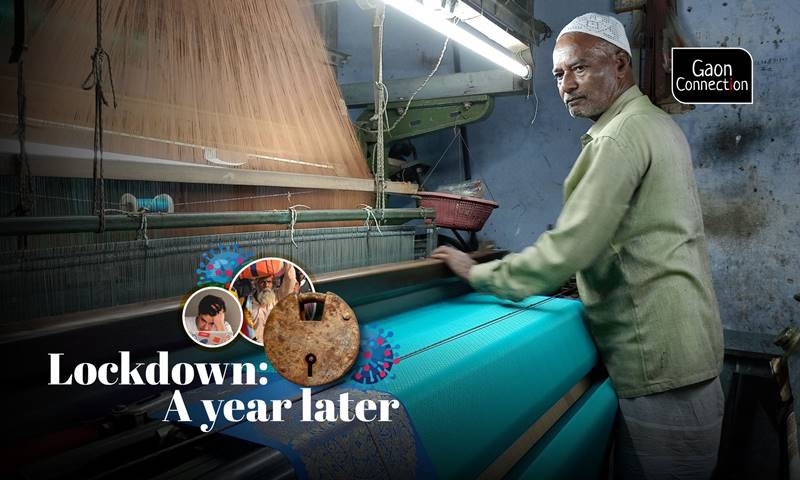

Varanasi is home to densely populated, congested lanes and bylanes that criss-cross each other like the warp and weft of fabric. Quite fitting then, that these are the sites of the city’s venerated textile industry that supports lakhs of weavers who produce the famous Banarasi sari and the other quality fabrics ubiquitous to the city.

But weavers in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Lok Sabha constituency have been worried for quite some time. The lockdown announced effective the midnight of March 24 last year continues to impact their livelihoods.

The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the physical distancing rules and the lockdown meant that the workers could no longer work in cramped spaces, like they did. This damaged the livelihoods of lakhs of weavers who have been in this trade for generations.

“Every two out of four handloom units are shut. Lockdown has been lifted, but there is hardly any demand in the market. Raw materials have become expensive, but there has been no support from the government. Due to lack of opportunity here, my brother Riyaz has now moved to Surat,” 45-year-old Gulzar Ahmed, a weaver in Varanasi’s Alaipur area told Gaon Connection.

Thirty five-year-old-Riyaz used to live and work with his elder brother before the trade was disrupted by the lockdown. He now works at a textile factory in Surat – the city in Gujarat known for its large-scale textile industry, and dubbed India’s Manchester.

Varanasi, 322 kilometres from Uttar Pradesh capital Lucknow, has witnessed the crippling economic effect of the pandemic. There are thousands of weavers like Riyaz, who have no option but to leave their own business and work for a much larger enterprise in states such as Gujarat and Maharashtra.

No one leaves happily. “Business did not pick up even after lockdown was relaxed. Demand has fallen and input costs and the price of yarn have risen. It wasn’t feasible for me to stay back home and work with my brother,” Riyaz told Gaon Connection over the phone.

“I had no option but to leave for Surat with my family. Here, I earn around six hundred to seven hundred rupees every day. If things had returned to normal in Varanasi, I could have earned a lot more than this. Coming to Surat has not resulted in a higher income, but what choice did I have when even living costs could not be earned in Benaras?,” he asked.

According to Power Loom Weavers Association, there are around 30,000 handloom weavers and 150,000 power loom weavers in Varanasi. Forty-year-old Faizul Rahman operates a power loom. Explaining his problems in running the business, he told Gaon Connection: “During the total lockdown, the condition was grim. People borrowed money to sustain themselves. Gradually, when the restrictions were relaxed, demand rose and we started getting orders in the wedding season. But that changed in November, when the cost of yarn suddenly rose,” he said.

From Rs 200 a kg, it shot up to Rs 280 a kilogramme in November. A single sari needs 300-400 grams of this thread. “Hence, the input cost increased by thirty to forty per cent,” Rahman added.

Power woes

Apart from the rising input costs, another factor has troubled Varanasi’s weavers — a hike in electricity prices.

In 2006, the Uttar Pradesh government had taken cognisance of the economic status of the weavers in Varanasi and fixed a flat rate of Rs 75 for a month for a single power loom. That changed in September last year — it was hiked multiple-fold to Rs 1,500 per power-loom per month.

The Yogi Adityanath-led Uttar Pradesh government faced protests from weavers’ associations across the state. Finally, after talks with the representatives from the industry, the government decided to provide electricity at a flat rate. But no government order has been issued till date.

“The inability of some weavers to pay the increased electricity bills saw them leave the trade. Many switched to operating tea shops or setting up small shacks to sell betel leaves and cigarettes,” Rahman told Gaon Connection.

Ramzan Ali, a local market councillor, stated that due to the government’s decision to do away with the relaxation in electricity prices, dozens of weavers in Alaipur also migrated to other cities to work as labourers.

“A lot of demand for our products comes from offshore locations such as Sri Lanka, Australia, the US and Canada. Due to international flight restrictions, we have not been getting orders,” Ali said.

Silk saris — the prime attraction in the array of textile products from Varanasi — require silk yarn to be imported from China. “The cost of silk yarn has risen sharply. It has gone up from two thousand seven hundred rupees to four thousand two hundred rupees a kilogramme,” Ashok Dhawan, patron, Banarasi Textile Industries Association, told Gaon Connection.

With such challenges thrown at them by the pandemic and the ruthless market conditions, it seems an uphill task for these weavers to ensure their age-old craft, and they survive.