Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh

“Will there be another lockdown?” asked a worried Vikram Sharma.

Till a year ago, the 30-year-old native of Mirzapur village in Gorakhpur used to work as a painter in Bengaluru, Karnataka. He earned Rs 700 a day. Now he spends time looking for daily wage work in the nearby city.

“I used to work as a painter in Bangalore (sic) before corona and lockdown happened. I have worked there for 13 years. All my savings are gone and I have nothing much to do here in the village,” Sharma told Gaon Connection. “I had planned about going back to Bangalore after Holi (March 29) but rising cases of corona might result in another lockdown.”

The reverse-migration in the aftermath of the nationwide lockdown that was announced in March last year resulted in Uttar Pradesh villages witnessing an influx of the migrant workers back to their homes — many of whom have no source of employment.

It’s been a year since then and these migrant workers have exhausted their savings, grown weary of being unemployed and are hoping to get back to their jobs in far off cities but a looming fear troubles them — another lockdown.

Sharma’s fears are not baseless.

India recorded 62,258 new COVID19 cases in the last 24 hours, the biggest single-day jump since October 17, taking the total caseload to over 11.9 million. Also, 291 deaths in the last 24 hours have increased the country’s total death toll to 1,61,240.

The soaring numbers, being blamed on the second wave of COVID-19, give weight to Sharma’s fears as states like Maharashtra and Gujarat have implemented restrictions in select areas to contain the spread of the coronavirus.

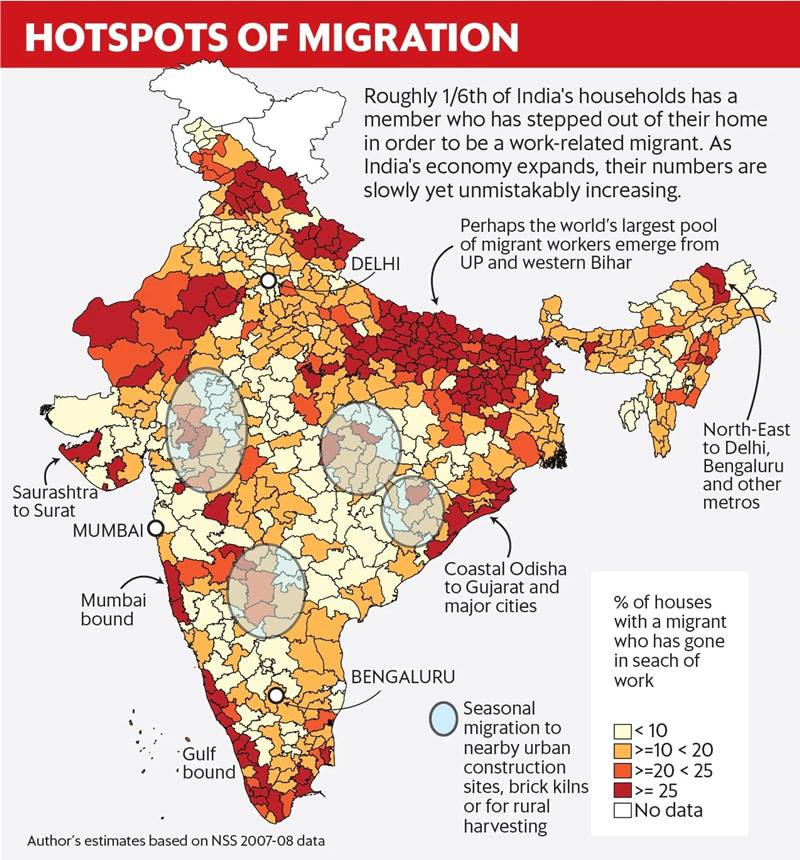

Gorakhpur — 330 kilometres from the state capital — is one of the biggest districts in the Purvanchal region of Uttar Pradesh which is home to lakhs of migrant labourers that work in other states across the country. As per the Uttar Pradesh government, around 4.5 million migrant workers returned home in the state amid the pandemic.

Also Read: Migrant Workers —The Indian government does not know their numbers, dead or alive

In such conditions, lockdowns are not out of question and millions like Sharma may have to wait and postpone their plans of returning to work in cities as they fear being stuck far from their homes like they did a year before.

Twenty-year-old Siraj-ud-Din who lives about 50 metres away from Sharma’s house in Mirzapur agrees with his neighbour. “Since the number of cases (COVID19) had stabilised and the businesses were picking up pace, I had planned about going to Hyderabad where I used to work as a labourer on daily wages. But, that’s not possible now as states have begun announcing lockdowns,” he said.

Also Read: During lockdown, rural India faced insurmountable sufferings; 74% satisfied with government

“In the months of April-May (last year), I was stuck in Hyderabad and all my money was exhausted. My family transferred money to the bank account of my contractor to help me and it was hard to survive the lockdown. I finally boarded a train in June to get back home. I don’t want to take the risk of being stuck again,” the 20-year-old added.

When asked about the financial condition and the employment opportunity within the village itself, 55-year-old Munni Lal, who lives next to Sharma’s house said that due to the large number of people coming back from the cities, there are far too many people to work in the fields and few employment opportunities.

“The only assurance we have in the village is that we will get two square meals a day despite not having money. It is the harvest season and we often work in the fields for which we get about ten kilogrammes of grains per day. So despite not having money, there are ways to survive in the village but it is not possible in the cities,” Lal told Gaon Connection.

“We also get our rations of wheat and rice from the government. That also helps us to sustain the hardship. But often there are delays and our supply is not enough to support my family of six members. But even then, I can think of surviving here in the village but it would be impossible in cities. I don’t fear corona as much as I am anxious about hunger,” he added.

He also informed that his daily wage was Rs 700 a day in Bengaluru and could manage to save Rs 300 a day after cutting the costs of living in the Karnataka capital. “I used to send this money back home and things were a lot better then. Now, we content ourselves if we have eaten for the day,” the disappointed 55-year-old told Gaon Connection.

Also Read: How did India’s most populous state Uttar Pradesh lead the COVID-19 battle?

On the opening day of the Parliament’s monsoon session on September 14, Santosh Kumar Gangwar, Minister of State for Labour and Employment, responded to a question asked by three members of parliament on migrant workers returning to their hometown during the COVID19 lockdown.

In a written reply, the minister informed that the government has no data on the number of migrant workers who lost their lives during their return to their hometowns, and so there was “no question of” compensation. The government, however, said more than 10 million (10,466,152, to be exact) such workers had returned to their hometown in the lockdown.

Presently, there is no credible data on the total number of migrant workers in the country. Estimates by government agencies and academic researchers range from 70 million to 194 million, a difference of over 124 million migrant workers.

Also Read: Almost every fourth migrant worker returned home on foot during the lockdown

In a first-of-its-kind national survey to document the impact of COVID19 lockdown on rural India, Gaon Connection had interviewed 25,371 rural residents, including migrant workers, across 23 states, and released the survey findings in August, last year. The survey found at least 23 per cent migrant workers returned home walking during the lockdown, 18 per cent by bus, and 12 per cent by train. While on their way home from the cities, 12 per cent migrant workers were reportedly beaten by the police.

About 40 per cent of this workforce faced food scarcity during its journey back home. Also, while stranded in cities, migrant workers and their families had to skip meals due to lack of money. For instance, the Gaon Connection survey found 36 per cent of migrant worker respondents skipped an entire day’s meal when stranded. Over 40 per cent reportedly had to skip one meal a day, as they did not have money to arrange for food.