Sugapankh, Mirzapur (UP)

Work-from-home is not an option for them. For, only when they step out and labour for eight hours a day can they feed themselves and their families. What they earn that day, they spend on food. Skipping work a day, or not finding work often translates into going to bed hungry.

The second wave of the COVID19 pandemic has made it worse for them as daily wage labourers have been pushed beyond their capacity to stay afloat in the pandemic.

Between December 2019 and December 2020, around 230 million people across India dived below the minimum wage threshold of Rs 375 per day, informs a recent report, ‘State of Working India 2021 – One Year of Covid-19’, by Bengaluru-based Azim Premji University. The report also highlights that women were worst hit by the job losses last year with 47 per cent of the women workers suffering permanent job loss.

Lack of employment is a major concern in rural India, and more so in the last one year of the pandemic as daily wage earners have lost their income sources.

Also Read: COVID19 impact: 15 million salaried workers lose job permanently, women workers suffer worst

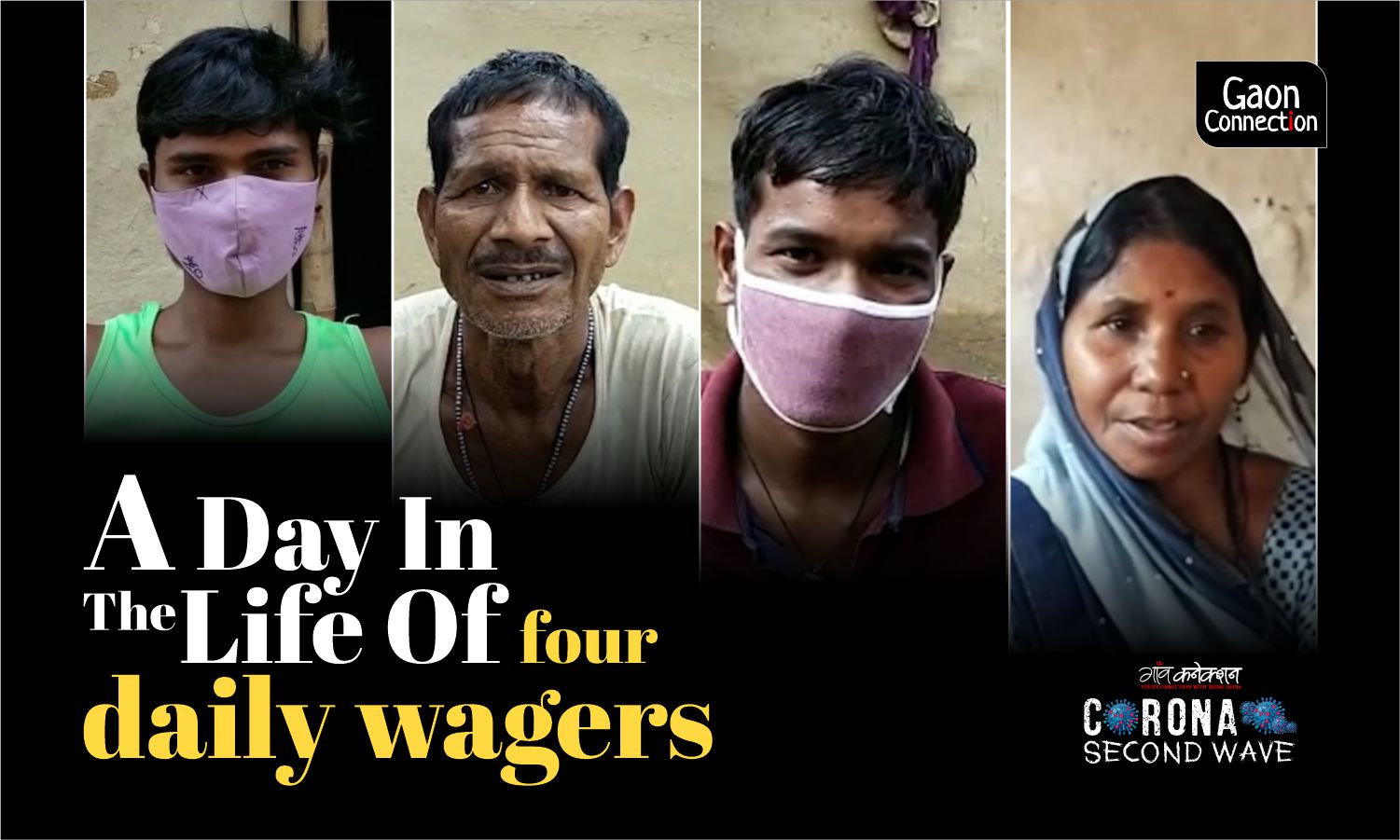

As part of its ‘A Day in the Life of’ series, Gaon Connection travelled to the hilly and predominantly tribal area of Marihan tehsil of Mirzapur district of Uttar Pradesh and spoke to some daily wagers, who have lost their livelihoods in the pandemic and are without any earning source.

Badri (55), farm labourer

Fifty-five-year old Badri Kol is a farm labourer who works in agricultural fields on a daily wage basis. A year back, before the pandemic started, he used to earn up to Rs 200 a day ploughing the fields or harvesting crops for landowners in his village.

But now, a large part of Badri’s day and night is spent sitting idle on the charpai outside his mud-plastered house in village Sugapankh in Marihan tehsil. Worry lines are etched deeply on his forehead.

Badri is aware of the ongoing mahamari (pandemic) and the risks associated with stepping out to work while the virus has spread deep into rural India. But, there is nothing he wants more than to go back to labour in the fields, Badri told Gaon Connection.

“Before the pandemic, I had a fixed routine when I would wake up, bathe, eat something and leave for the fields where I worked as an agricultural labourer and,” he said. “On my way back home I would pick up vegetables and groceries that we would cook and eat at night,” he added. Badri’s family consists of his wife, two children and old parents.

Also Read: Rising hunger stares rural India in the face as the second wave of COVID invades villages

Now there is no work, no money and therefore not much vegetables and groceries either. The family is surviving on meagre government rations. Corona curfew is in place till May 31. “I am tired of sitting around doing nothing, worried and anxious all the time,” Badri lamented.

“We have had no work ever since the wheat harvest. We are sitting home,” Badri said. Most of the breadwinners in the village hope that sooner than later they are able to go back to their earlier lives. “It was a hard life, but we prefer that to sitting home, wondering where our next meal is coming from,” Badri concluded.

Meera Devi (44), farm labourer

Seven out of 10 rural women in India work in the agriculture sector, mostly as daily wage labourers, under highly exploitative working conditions. Meera Devi is one of them.

“I used to work as a farm labourer and earn about hundred and fifty rupees a day. But, all that has stopped now. There is no work in the village,” Meera, sitting amidst her pots and pans and a smokey chulha in her very sparsely stocked kitchen, told Gaon Connection.

Meera, a resident of Sugapankh village, has always worked at home as well as outside in the fields as an agricultural labourer.

“Before the mahamari, I used to wake up early in the morning, cook for the family, wash vessels and finish all household chores and head out to work in the fields. But now I have nowhere to go and there is no income,” the 44-year-old told Gaon Connection.

However, she continues to work at home — pandemic or not. “My morning routine has not changed. I still wake up, cook and do my household chores. I also take my two goats out to graze during the day,” she said.

Unlike Badri, for Meera the work has not completely stopped, but her income has.

Ajay Kumar (22), migrant worker

“I worked in a glass factory in Surat and returned home once lockdown was announced earlier this month,” Ajay Kumar, another resident of Sugapankh village, told Gaon Connection. “I had a good thing going there. I would go to work in the mornings and return home at night and always had enough to eat and send home,” he said.

Ajay Kumar took the decision to return home because the number of COVID19 cases in Surat, Gujarat was rising and he was scared to stay on.

The 22-year-old, who came back to his village on May 13, has stopped trying to go out to look for a job because the police come down heavily on anyone who they see wandering around. He used to earn Rs 10,000 a month back in Surat and said he could support his family of 10 with that. “My factory in Surat is still functioning,” he said wistfully.

Also Read: “We will eat sookhi roti and namak, but at least we will be home”

Shiv Shankar (19), construction labourer

There was a time when 19-year-old Shiv Shankar was earning up to Rs 300 a day as a construction labourer at Mirzapur town, and it ensured his family did not go hungry. “But now there is not a paisa coming in by way of income,” said Shankar as he sat, masked up, idle outside his kaccha house in Sugapankh village.

“We do not want to go back to the big cities any more, but even in the smaller towns there are no jobs for us. And even if there was, how would we get there with no transport,” he asked. He lives with his wife, two children and parents.

Also Read: The trauma of last lockdown still fresh, migrant workers make a beeline for home

It is not for want of trying. But with no jobs and curfew/lockdown restrictions in place, many of the migrant labourers like Shankar who earned on daily wage basis and have returned home are wondering if they did the right thing.

Government response

Authorities are not unaware of the hardships faced by the daily wage workers and other labourers in the unorganised sector.

On April 23, the Indian government announced free food grains (rice or wheat) to the poor under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana. Around 800 million beneficiaries will receive five kgs grain a month in May and June this year. This allocation is over and above the five kgs of food grains per month each beneficiary is entitled to under the National Food Security Act, 2013 (NFSA).

Also Read: Centre announces 5 kg free grains a month to the poor for May-June; experts seek extension

The Uttar Pradesh government has also announced additional free foodgrains to 14.5 million poor beneficiaries for May and June. On May 21, Renuka Kumar, additional chief secretary, Uttar Pradesh, tweeted that the state government would provide an allowance of Rs 1,000 a month to unregistered workers.

The rations may have brought temporary relief, but will they tide over the crisis? “When will things turn around,” is the foremost question in the minds of Meera Devi, Badri, Ajay Kumar, Shiv Shankar and thousands of others like them who are home with their families, but are now anxious about getting back to work.

“Most of us are left with no means of livelihood. We are surviving by borrowing money from relatives and neighbours. But for how long,” Ajay Kumar asked.

Written and edited by Pankaja Srinivasan.