Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh)

It’s been more than two months since the nationwide lockdown was announced on March 24. During the course of this lockdown, the country has witnessed reverse migration of labourers. Many of those who had moved to big cities to make a living lost their jobs during the lockdown, didn’t receive their salaries or had to struggle to get daily meals. Dejected, they started moving back home – by trains, in trucks, or on foot. These journeys weren’t easy.

These labourers vowed never to go back to the cities again. But after living in villages for a few days, they realised that there are no job opportunities here and some have already started moving back to the towns and cities even though the lockdown hasn’t even ended.

“There is no work. Hunger still looms over us. All our savings have been used up and the expenses remain the same as ever. Where else will we go? We need to find some work, so have come back to the city in order to do that,” said construction worker Shiv Kumar Nirmal, who arrived in Lucknow from Tikariya village in Sultanpur district of Uttar Pradesh despite the lockdown.

Shiv Kumar arrived in Lucknow 10 days ago and now he waits, each day, with other labourers like him, at an intersection – popularly known as addas — to get some work. He said: “We have been here for 10 days, but have not earned a penny. For how many more days can we survive without work?”

Like Shiv Kumar, construction worker Hukumveer has also returned from Hamirpur village in Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh on May 21 in search of work.

He said: “We were told that construction activities would soon start in Lucknow, so four-five people from the village came here on our bikes. No one asked for any pass or permit.”

Like daily wage labourers Shiv Kumar and Hukumvir, Sonu Kumar, who had gone back to Ramkarwa village in the Hardoi district during the lockdown, have now returned to Lucknow looking for some work.

Sonu said: “I came to Lucknow on May 23. Since then I have been coming here every morning, but there is no work. Only a few labourers have been coming here so far who have somehow managed to reach the city.”

When asked why didn’t they undertake jobs under MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) in their respective village, Sonu said: “MGNREGA work has not yet started in my village, so I have come here. I have taken a loan. I still have to repay Rs 9,000-10,000, which I hope to repay over a period of time once I start earning.”

There is a considerably increased load of debt upon these labourers due to the non-availability of ration and loss of employment during the ongoing lockdown. A report was submitted on the basis of interaction with 3,127 workers during the lockdown by Jan Sahas, an institution working on human rights of socially marginalized communities. As per this report, 78.7 per cent of migrant workers are stressed about the inability to repay the loans if they don’t get jobs.

Like Sonu, Mahendra could not go to his house and was trapped in Lucknow due to the lockdown. Mahendra is also looking for work every day for the past six-seven days. In cities like Lucknow, there are many centres, called labour addas, where from people hire them for jobs like construction, painting, digging foundations, carpentry, etc. But nowadays, these addas have fallen quiet.

Mahendra said: “I have incurred a debt of Rs 10,000 so far in the lockdown and not found any work. I am simply managing by borrowing. The rent needs to be paid too. I get Rs 400 as daily wages. I would repay when I will start earning.” He added: “There is hardly any work right now. If at all someone comes, one or two labourers get some job, otherwise everybody returns empty-handed.”

This intersection of Rajajipuram has been thronged by construction workers for years. In the morning, 150 to 200 labourers used to be gathered here in the morning, but these days, hardly 20-25 labourers are seen on the road during the lockdown.

“There is a general atmosphere of fear due to the lockdown. It is difficult to stand at the crossroads. We also worry whether we’d find some work or not. Nevertheless, we have returned to the city in a hope of finding some work,” said Rupesh Kumar, another construction worker, who returned to Lucknow on May 21 from Mawai village, which is in Hardoi district.

“We cannot work with a shovel”

When asked why didn’t they stay back in the village and take up jobs under MGNREGA, Ashok Kumar, another labourer, said: “We are painters. We know painting and that is what we’d do. The MGNREGA jobs involve working with a shovel and carry mounds of dirt. We can’t do that.”

Skill mapping of labourers returning home in Uttar Pradesh is being carried out. Around 24 lakh labourers and workers have returned to their homes in Uttar Pradesh so far. Until May 22, more than nine lakh labourers and workers had also had skill mapping done as to what they do. Under skill mapping, data is being prepared under 64 trades, including construction workers, painters, drivers, nurses, motor mechanics etc.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath said that he is trying to ensure employment within the state in accordance with their skills by creating a migration commission with skill mapping. There is a large number of labour force in the state.

In the country, if one considers the labourers associated with construction activity, it has the highest number of 5.50 crore workers who contribute nine per cent of the country’s GDP. It is their compulsion to return to cities in search of work during the lockdown.

Rakesh Kumar, an elderly labourer, who is looking for work at the same intersection of Rajajipuram in Lucknow, is from Bilwa village in Etawah. On the question of getting work in the village, Rakesh said: “I have left the village for good. I have to earn and live here. I have no farming land, so have to work here to support myself.” Rakesh, like all other labourers, has been coming and standing at the same intersection for the past six or seven days.

The state government had announced an economic relief package on March 20 for these labourers who had lost employment due to the lockdown. It had announced an allowance of Rs 1,000 per month to each of the 20.37 lakh construction workers and 15 lakh daily wage workers to meet their daily needs. The state government has also appealed to the labourers on May 27 to activate their bank accounts immediately if they had become inactive so that such workers can withdraw their maintenance allowance.

“I would have got Rs 1,000 if the card was renewed”

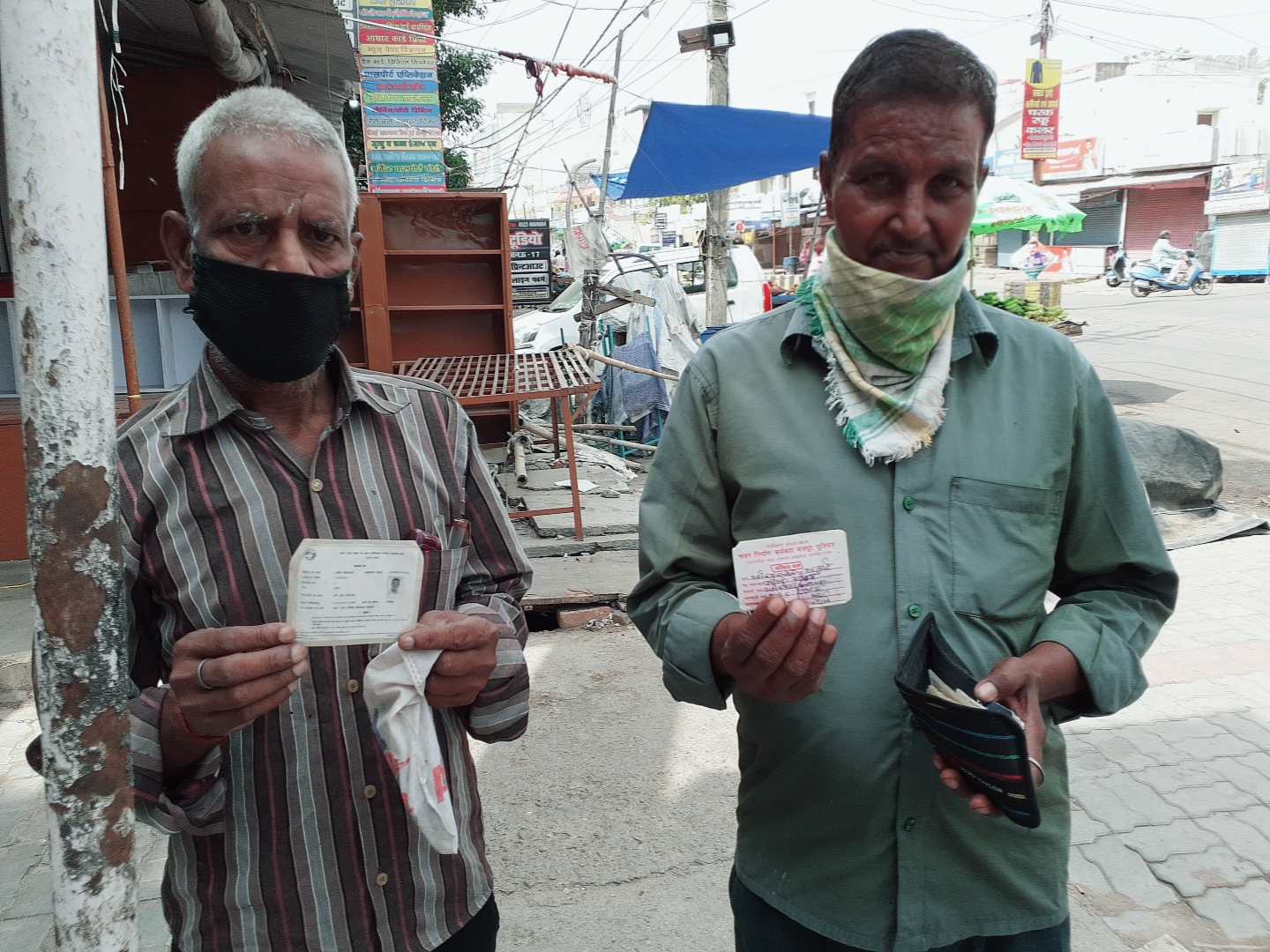

Did you get any help from the state government during this lockdown? Ashok Kumar showed his organized workers’ card and replied: “I had got this card made, but did not renew it for a year or two, so we did not get any help. It was indeed foolish of me not to renew the card. Today I could have benefited had I done so.”

Rakesh, who was standing next to him, said: “We did get the government ration twice, based on the number of people in the family. At least, this much we got.”

Lockdown-4 is now going to end on May 31. Work has also resumed with some guidelines. However, employment has now become the biggest necessity for the labourers who had been feeding themselves and their families by earning daily wages and had borne the biggest direct brunt of the lockdown.

Many labourers stranded in other states will not come back

There are many migrant labourers who were trapped in other states and had registered for a ticket to return home by train. They are now staying put due to the commencement of work there.

Guptchand, who was trapped in Kullur in Karnataka, is one of them. Guptchand, a resident of Maharajganj’s Atta Bazar in Uttar Pradesh, decided not to return home when work began in Karnataka.

“Slowly, the work has been started in Kullur since May 4 and I too have got a job, so what will I do now by going to village. This is why I have decided to stay and work here now,” he said.