India’s demographic landscape is transitioning towards a young population, with an average age of 27 years. Given this, it is critical that we recognise the needs and aspirations of this young population and invest in them, particularly when it comes to policy. Only then will we be able to realise the true potential of this demographic.

Till date, Indian policymakers (government, corporates, and civil society) have proactively brought in strategies around education, skilling and entrepreneurship, to reap this demographic’s potential. However, they’ve had mixed success. This can, in part, be attributed to the fact that they have not accounted for the aspirations of young people in their policymaking.

Currently, there are three lenses that define youth development at a policy level.

1. Economic lens: Employment, entrepreneurship, skilling, and education

This lens focuses on young people’s contribution in enhancing the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It views the youth demography as economic capital and thus addresses them as workers and consumers.

In this regard, the National Youth Policy (NYP), 2014 strove to create awareness about job opportunities and financial packages available to young people. The NYP also sought to improve the quality of skilling institutions and promote higher education, as well as boost entrepreneurship through customised programmes for different ages. For the latter, some of the steps recommended by the policy include: scaling up existing training programmes, and working with civil society and private players to include marginalised youth; running programmes for young entrepreneurs that provide support on business planning and execution; and implementing monitoring and evaluation systems for them.

So far, we have had some successes on the efforts taken under the economic lens, such as the 85 lakh new jobs created between 2016-19 under the Pradhan Mantri Rozgar Protsahan Yojana; 50 lakh young people trained with a placement rate of 57 percent between 2016-20 under the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY); and the INR 8.93 lakh crore worth of loans sanctioned under the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY) between 2015-19.

However, gaps persist. And these have only been exacerbated by the pandemic. While the unemployment rate peaked in May 2020 at 23.5 per cent, for the first week of July, it settled at 8.9 per cent, which is still higher than the pre-COVID-19 levels. More recently, in September, it was 7.3 per cent.

The Indian economy was already slowing down by mid-2019, and while the quantity of jobs available was a problem, we also saw more positions lying vacant. Several policy questions are thrown up by this paradox: Has the Indian youth become more discerning about their career needs? Have passion and interest and therefore the ‘right vocation’ become more important than before? Could that also explain the low skilling rates—only 6.25 per cent of the overall skilling targets under various government schemes has been achieved? Could the low rates of higher education enrolment be possibly due to the same reason—that we don’t equip students to solve real life problems? India’s Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) in the 18-23 age group was 27.4 per cent for 2017-18, against the comparable global average of 38 per cent.

2. Protection lens: General, mental, and sexual and reproductive health

Due to COVID-19, millions of adolescents in India are now unsure about their financial futures, with a lack of personal space, separated from their friends. They are exposed to widespread fear, compounded by constant news about death and disease which creates uncertainty and apprehension. There has also been a rise in cases of domestic violence and sexual abuse. Even prior to the pandemic, research has found that the onset of most mental and substance abuse disorders (MSUDs) occur at a young age or during adolescence.

At a policy level, the NYP 2014 advocates for improving service delivery to remote areas and providing adequate healthcare access, especially to women. It also calls for generating awareness on preventive healthcare and healthy lifestyles, and of the effects of drug and substance abuse, through inclusion in school curricula. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare had launched Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) in 2014 to reach out to 253 million adolescents, with a special focus on those from marginalised communities. It sought to shift from existing clinic-based curative approaches to focus on a more holistic model based on a continuum of care, including the provision of information, counselling, and health-related services.

Despite the promise of RKSK, which is yet to be realised, and increase in health outlay—though at below 1.2 per cent of GDP, it is much below global average of six per cent. We’ve seen how the pandemic has further exposed the gaps in our public health infrastructure. Given these shortcomings, steps that policymakers could take to strengthen efforts under the protection lens include:

- Providing access to quality health services, especially in remote and conflict-ridden areas, while upholding the dignity and choice of young people

- Standardising preventive mental health practices in educational establishments

- Embedding comprehensive sexuality education in school curricula

- Encouraging public and private healthcare spaces to set aside budgets and undertake research on youth-related issues

- Enabling young people to take charge of their lives and have them address practices like child marriage and gender-based violence in their communities

3. Social dividend lens: Social entrepreneurs, nonprofits, volunteers

The NYP 2014 envisioned young people to become proactive citizens by instilling social values through school curricula, community engagement through schemes such as the National Service Scheme (NSS) and the Nehru Yuva Kendra Sangathan (NYKS), and by prompting social entrepreneurship. The NYP also incentivises youth to participate in politics by promoting youth participation in civic and social justice issues. Some ways to achieve greater political participation by the youth, as highlighted by the NYP, are:

- The Rajiv Gandhi Panchayat Sashaktikaran Abhiyan (RGPSA), run by the Ministry of Panchayati Raj, which focusses on building the capacities of members of the Panchayati Raj Institutions, including youth and first-time elected representatives

- The Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellowship (PMRDF) run by the Ministry of Rural Development, which gives young people an opportunity to work on programme implementation in certain districts of the country

A UN study titled State of Youth Volunteering in India (2017) shows that volunteerism for social work among youth is on the rise in India. Yet, these activities are not often perceived as legitimate career options, especially when pitted against the pay scale of the corporate sector, or the status and security afforded by government jobs.

There is a lot more that policymakers need to do to pull young people towards volunteering, change-making, and social entrepreneurship. Steps that can be taken include:

- Ensuring that the Ministry of Youth Affairs sees to it that youth-related concerns are reflected in other departments and ministries as well

- Creating a system of rewards to incentivize youth to engage with political institutions

- Encouraging companies with a youth-heavy workforce to promote volunteerism

We need for a fourth lens for youth development

While the intent of policymakers may be positive towards engaging the young, a key element might have been missed: The changing aspirations and psychological developmental of young people.

Today, a lot of young people are engaging with questions of identity, the self, and society at large. Along with questions such as ‘Who am I?’ are questions such as ‘Who are we?’.

We need a psycho-social-economic lens that not only caters to what society from young people, but is centred around the needs, aspirations, and anxieties of young people. Instead of focusing on the young transforming the world, the focus under this lens would be on helping them reflect on how the world is changing them—a subtle but important shift in the viewing point.

Strategies under this psycho-social-economic lens will have to be co-developed with the youth. For this, policy makers will have to ensure proportionate representation for youth in decision-making bodies. We should enable young people to share power with adults. Without this, policies will continue to be vertical, top-down affairs, with little or no impact on the young.

We, at vartaLeap, have initiated the concept of a Jagrik, or Jagruk Nagrik—a self-awakened, proactive, young citizen who is enabled to invest in their own self-discovery and development through social action. To develop the idea of a Jagrik, we are promoting and nurturing a broad-based coalition of corporates, civil society organisations, and government institutions to co-create an ecosystem for youth leadership. Members of this coalition work across diverse issues that have impact on young people, their needs, and their potential. We want to enable young people to invest in their own self-discovery and development through social action.

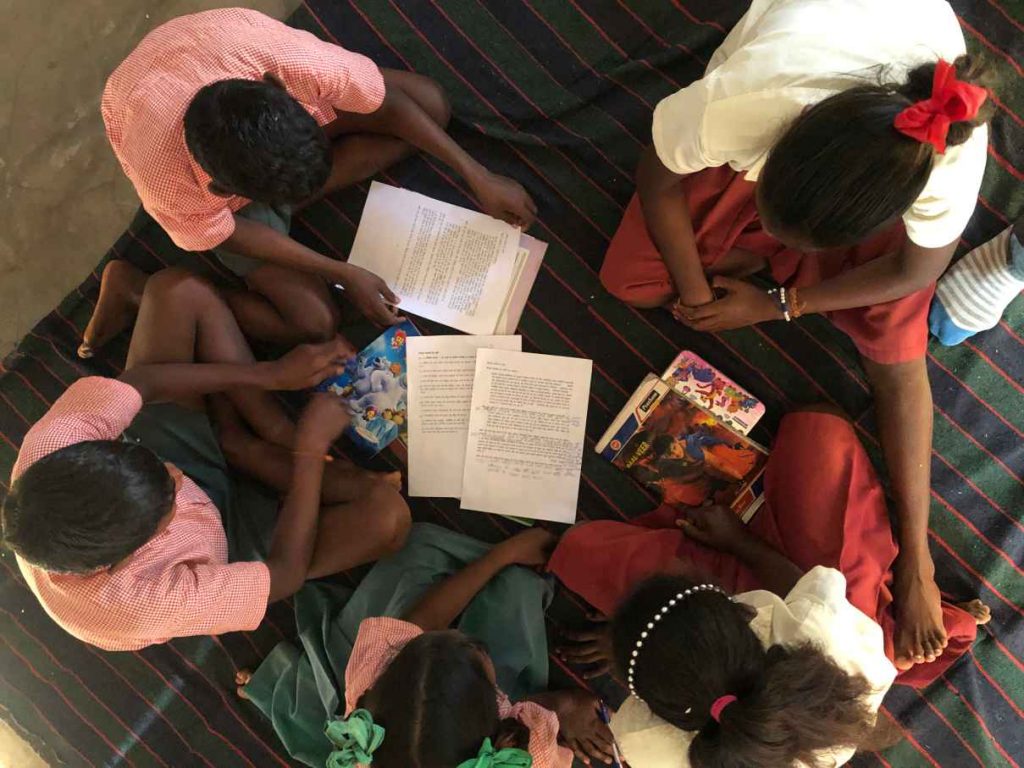

This journey is facilitated through educational games that enable young people to work on projects on issues such as constitutional literacy, health, child rights, and so on. They engage with relevant duty bearers to put forth their opinions and demands, and perform their duties as citizens. Jagriks carve out their own leadership journeys by mainstreaming school drop-outs, making efforts at protecting the environment, enabling access of disabled adolescents to school services, spreading awareness on the need to educate girls, and more.

The world over, younger heads of state are becoming the norm. For instance, Justin Trudeau (Canada), Jacinda Ardern (New Zealand), Sanna Marin (Finland), Sebastian Kurz (Austria), Katrín Jakobsdóttir (Iceland), and Leo Varadkar (Ireland) are all under the age of 50. But to make this happen, we need the youth to gain experience in governance and learn the complex art and science of decision-making early on. Only then will India see its first head of state under the age of 50.

This story has been sourced from India Development Review. You can read the original story here.