Lalitpur district, Bundelkhand, Uttar Pradesh

In time, Independent India has come a long way, pushing many social evils and regressive, exploitative practices away from wider public memory. This doesn’t mean these practices are not alive in different pockets of our country. The ‘affluent’ exploiting the ‘poor’ and the latter finding no redressal – be it in metro cities or in villages – are (un)comfortable truths we live with and not do much about. In rural India, the moneylenders – locally referred to as lala, sahukar, bania or seth – cheating and looting the poor are still rampant.

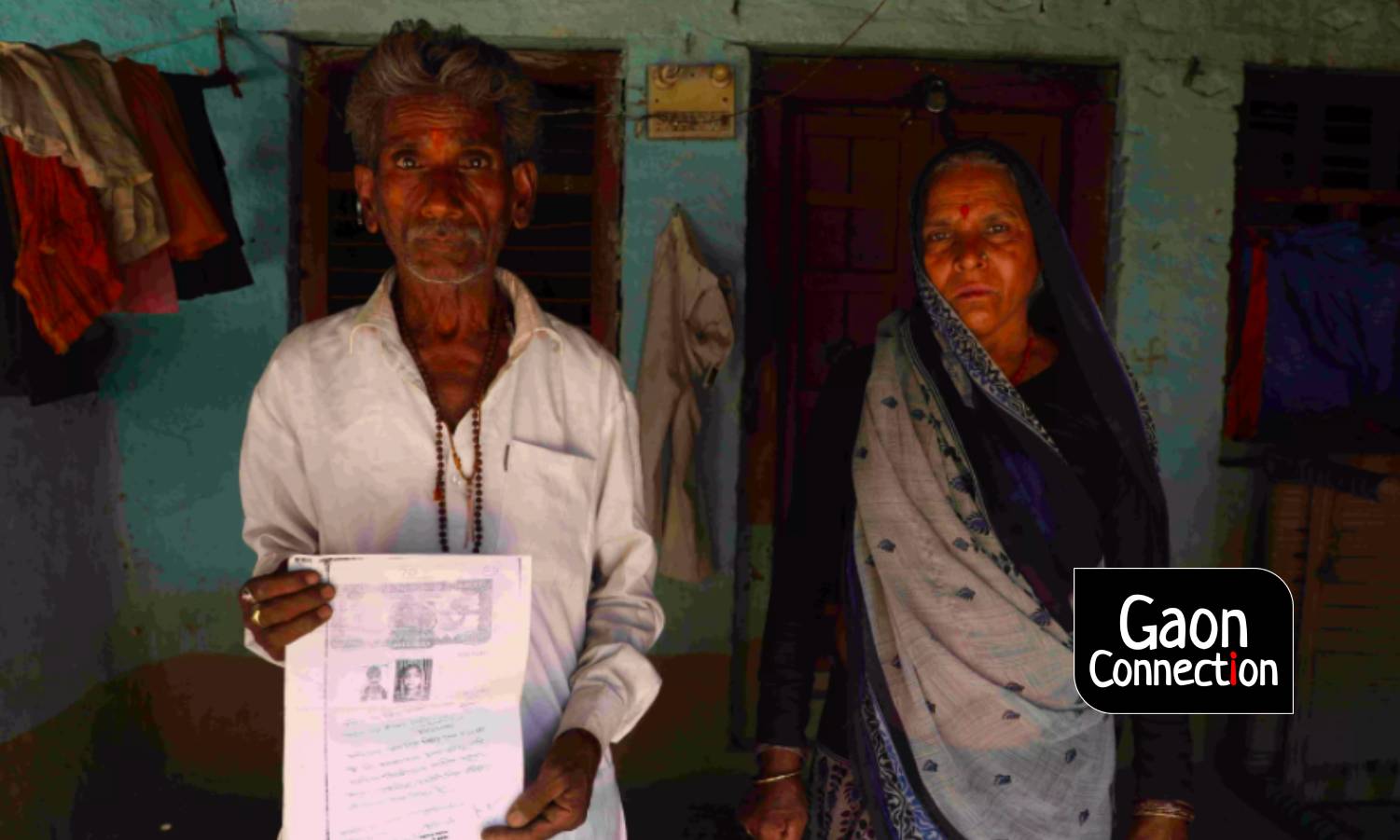

The Gaon Connection team was in conversation with Mathurabai Gadaria and Baghwandas Gadaria of Gagania village of Lalitpur district in Uttar Pradesh’s Bundelkhand region. The conversation was about their legal battle against an affluent man in the village they took a loan from.

“I mortgaged an acre of my farmland for Rs 26,000 to arrange money for my son’s treatment. I had already spent Rs 1,50,000 on it by selling my jewellery and taking other loans,” Mathurabai told Gaon Connection. “The bania was dishonest. He took away my entire four acres of land. Both my son and my land are gone,” she sobbed, burying her face in her pallu (the loose end of a saree).

In one part of the world, man is planning to inhabit Mars, but, in another part, in rural India, the poor are exploited to no end. Mathurabai’s son is no more. This son’s wife chose to live with her parents and left with her children long ago. Their second son is settled with his family in Haryana. The elderly couple is counting their days and cursing the moneylender for their misfortune.

Bundelkhand is infamous for farmer suicides, droughts, and migration. Taking loans is an unfortunate yet unavoidable event in the life of farmers inhabiting the rocky, inhospitable terrain of Bundelkhand and facing frequent drought. Most of the land is not cultivable and the areas under cultivation often suffer ravages of harsh weather. Due to their crops being ruined, farmers are forced to take loans. They are then trapped in the vicious cycle of debt. The mounting debts compel several farmers to commit suicide. Often, debts are also passed on from one generation to the next.

Bhagwandas and Mathurabai belong to the Gadaria (herder) community. The contested land was given to them on lease by gram samaj in 1992 because Mathurabai allowed for tubectomy under the family-planning drive. She grieved the loss of land more because she believes she paid for it using her body.

Bhagwandas, on March 13, 2008, took a loan of Rs 26,000, at two per cent interest, from a moneylender in Mehroni, pledging an acre of land. Later, he took a crop loan from a bank through Kisan Credit Card (KCC) against his remaining three-and-a-half acres of land and repaid Rs 50,000 to the bania.

Bundelkhand reeled from a severe drought in 2015. The following year, land-owning farmers in the area were compensated by the government for the crop loss. All land-owning farmers except Bhagwandas received the relief money. When they checked with the patwari, they learned that, as per records, Bhagwandas had forfeited land rights to the moneylender.

When he confronted the moneylender, the latter rudely dismissed him and threatened him with life, Bhagwandas alleged. “Since the bania threatened my husband again, I tried talking to him, but he did not relent. We sought police intervention, but in vain. Finally, we had to seek legal action,” Mathurabai told Gaon Connection.

After pursuing the bania for two years in vain, Bhagwandas had to procure a court’s order to lodge an FIR at Mehroni police station on April 26, 2018. The police registered a case under sections 420 (Fraud), 120 B (Criminal conspiracy), 467, 468, 406, and 471 (Forgery) of the Indian Penal Code. The matter is presently under consideration in the court.

What the accused say

The Gaon Connection team was not able to talk to the accused during its stay in Bundelkhand but later when contacted on the phone, the accused in Bhagwandas’ case denied all the allegations as baseless and motivated by enmity.

“Firstly, I do not give out money on mortgage or interest. Secondly, the land is not in my name. When Bhagwandas got the land registered, I was there in court as a witness,” the accused said. “The charges are all fake. They have filed two civil cases against me. The court’s judgement will be obeyed by all,” he added.

“Bhagwandas said they would like to continue farming on the land. The registry took place in 2008 and for seven-eight years, these people gave us a share of the produce. Later, however, somebody misled them. Their intentions changed and they moved legally,” the accused said when we asked why his relative, who is now the owner of the contested land, didn’t claim ownership since 2008.

As per the accused, Bhagwandas is a drunkard and a liar. He claimed Bhagwandas’ late son was present at the time of the registration. “Why did he raise the issue only after 10 years?” he asked.

The revenue records show that the ownership of the one-acre land was done on April 15, 2018, 35 days after the registry whereas the remaining three acres of land were filed for mutation seven years later, on July 10, 2015.

A similar story

Like Bhagwandas, Jagannath Pal of Amaura village in Lalitpur district had owned five-and-a-half acres of land. He has three sons. The eldest son Ramkishan had taken up farming. He leased fields of other farmers too, for cultivation. Everything worked well till the day he ran into debt.

“The baniya I used to have frequent dealing with once expressed his desire to cultivate in partnership. We contracted 40 acres of land. “We will take the cost and split into two,” he had told me but he piled all the farming expense on me and mortgaged my land,” Ramkishan told Gaon Connection. “I hoped to reclaim my land, but it did not happen,” he sighed.

As per Ramkishan, such large-scale cultivation would have drawn expenditure in lakhs of rupees towards fertilisers, seeds, and diesel. What he understood was that the moneylender would shoulder the cost of cultivation and would split the net income in two, giving him one half. Ramkishan’s labour had also borne fruit and produced a bumper crop at that time.

“That year, we got 300 quintals of barley on the leased land and 50 quintals of wheat from our fields,” recalled Ramkishan. “There was an expenditure of about Rs 2.5 lakh. However, the bania did not share any of the expense and took the entire yield (300 quintals barley and 50 quintals wheat). I also had to give him Rs 50 thousand as he turned the cost into debt in my name. He had not shared details of the account with me. I had continued to work in good faith,” he said.

Ramkishan’s brother Ramdas is also disillusioned with the system. After what they suffered, he believes that government claims to help the poor are hollow. Ramdas accused the moneylender of intimidation and bemoaned administrative apathy. He works in Indore as a labourer. He returned during the lockdown but will go back to Indore once the pandemic passes.

Ramkishan’s other brother Moti explained how farmers in Bundelkhand fall prey to debts. “No one can function here without loans, and you have to either pawn jewellery or mortgage land to get a bigger sum of money. When the bania gives a loan, he deliberately lets it be until it mounts up to a huge amount. He is then free to confiscate all gold, land, or houses as pledged by the victim,” he said.

The fraud just doesn’t end there. The moneylender bought Ramkishan’s land, in acres, for cheap rates. The bania also made Ramkishan spend on some land in another village. “He advised us to sell the village land that was costly and find land elsewhere with his help. Following his advice, we sold the land, but he connived again to appropriate the new land we bought in another village in his own name. The money was mine but the land became his,” Ramkishan said.

How do the moneylenders operate?

A social worker from Lalitpur, on the condition of anonymity, informed Gaon Connection that Bundelkhand has a flourishing business of moneylending worth crores of rupees. Money lending for up to 20 thousand rupees is common not only in Bundelkhand but across thousands of villages in India. Bigger amounts of money are provided by traders and moneyed people from the cities. These people give money to the farmer against the latter’s assets. The farmer gets the money but is also subjected to overall exploitation.

For example, if a farmer mortgages one acre of farmland for Rs 1 lakh and the registration amount for that is Rs 20, 000, it will have to be borne by the farmer. For this, the borrower will either be given only 80 thousand in cash or his debt would increase to Rs 1,20,000. Sometimes these costs are hidden. Secondly, if the farmer wants to repay and get his land back, he will have to shell out money again for the registration. It is almost impossible to escape from the clutches of moneylenders and the debt, once trapped.

Gaon Connection withheld the names of the accused since the matter is sub judice.

Arvind Singh Parmar contributed to this report.