Anyone seeing Hansal Mehta’s Aligarh would have felt the undercurrent of affection between the director and actor Manoj Bajpayee.They go back a long way, but did you know then that the two did not speak for quite a few years in between? If Mehta knew Bajpayee was attending a party, he would not go. If they met in public, they’d look the other way.

And then, when Mehta ran into Bajpayee while working for director-producer Sanjay Gupta, the two looked at each other and burst into laughter, and wondered why they had let the years slip past.

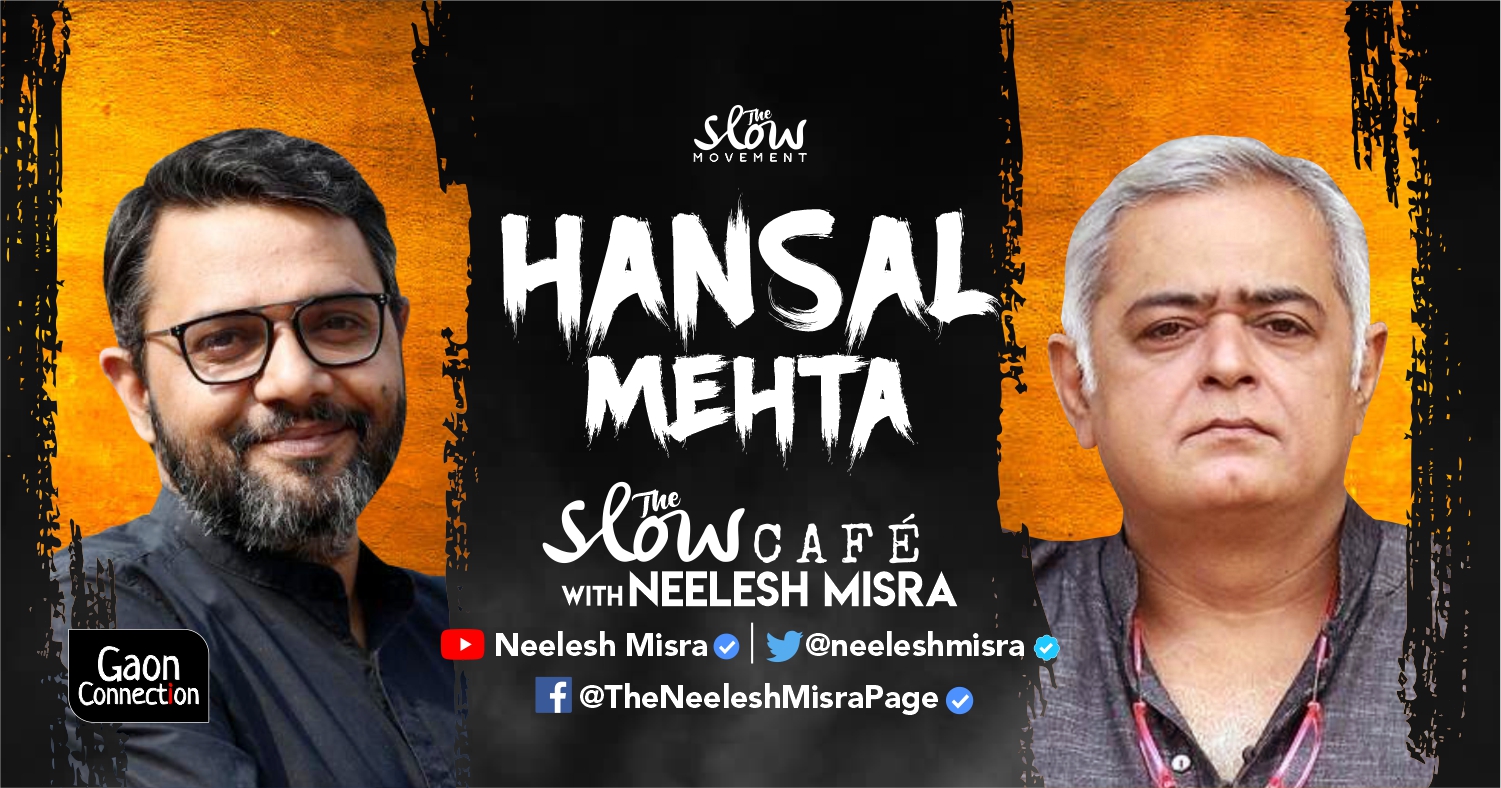

Neelesh Misra’s The Slow Cafe is a sort of happy confessional chamber, where people share things they normally would not dare mention in public. Oh, by the way, Mehta also had a running feud with Vishal Bhardwaj for a long time he said adding that Bhardwaj was his first friend in the industry. But they did patch up and wondered why they had fought in the first place.

Now that the fights are dispensed with, Mehta’s is a saccharine-sweet story, one which speaks of resilience, of human bonds, and the creativity that unites the like-minded.

The director of new-age classics such as Shahid, Aligarh and Omerta, is now revelling in the praise coming his way for Scam 1992 on SonyLIV. The series is on stockbroker Harshad Mehta’s life, and based on the 1993 book The Scam by Sucheta Dalal and Debashis Basu.

“When I first read the book, I was fascinated by the story of this Gujarati boy in Bombay. I was in Australia then, and my friends would tell me about the money they invested in a certain company’s share. And then, I read about what Harshad did. My friends lost their money,” Mehta told Misra. When Harshad died in custody in 2001, Mehta started reading up about him again. “He was the tragic anti-hero. He was neither black or white and I wanted to explore his world, but was not able to for many, many years,” he said on the show.

It did not help that Mehta had made a sex comedy Yeh Kya Ho Raha Hai? in 2002. “I got stereotyped. Where could I make a film about Harshad Mehta? Everyone thought I would turn him into Hugh Hefner,” he laughed. It took him time, and a spate of movies that won critical acclaim before he could begin work on this. “Sameer Nair had bought the rights, and I read the book again and realised it was perfect for a slow series, quite like this conversation. I began work in 2017 and it took three years to make,” he said.

Does a creator feel an emptiness when a film is wrapped up, asked Misra. “I’ve been doing this for long, but maintaining a balance becomes difficult. I’ve just started doing that. You live together with the characters and begin to know them. There is a lot of romance and passion, and then in editing you retain all the good and remove the bad. It’s a strange privilege that you do not get in life. Yes, there is angst, and you try to run from it. At some stage, there is a detachment and you feel the emptiness. The process is beautiful, though.”

Speaking of his initial years in Bombay, Mehta spoke of how making Scam 1992 was a chance to speak Gujarati again, a chance to call Mumbai Bombay again. It was an act of rebellion and nostalgia, all at once. “Like Pankaj Kapur says in Maqbool, ‘Bambai meri mehbooba hai’,” he laughed.

Mehta had a simple childhood in a bungalow where his homeopath grandfather was a tenant. And, he’d sublet a portion to the great playwright Vijay Tendulkar. Among his grandfather’s patients were top actors including Dilip Kumar, Goldie, Dev Anand, Manoj Kumar and Rakhee, who was just beginning her career. His grandfather was assisted by a lady who would go on to become the mother of award-winning actress Shefali (Shah). So, there was a writer, a future actor and a director, all linked to that one person, his grandfather.

“Years later, when Paresh Rawal took me to meet Mr Tendulkar for something, and I mentioned my grandfather, he stopped speaking about work and asked me if I was Deepak’s son. And then, we spoke about how the landlord would not allow him to write at all in that house,” said Mehta.

These connections would continue to grow later in life too. Through Bhardwaj, Mehta met Ashish Vidyarthi, through him Manoj, and through him, Anurag Kashyap. “I was surrounded by this energy,” he said.

In his home in then Bombay, Mehta grew up amid trees that generously bore guava, mangoes and phalsa, enough to share with the entire neighbourhood. But, Mehta’s parents were faced with a difficult problem when he was in his late teens. He was terrified of being alone at home. And so, he accompanied them to movies teens normally did not prefer. So, Shyam Benegal’s Ankur and Manthan, Mahesh Bhatt’s Saaransh… were all watched.

“We would go to Bandra Talkies. The ticket was two rupees and there were balcony and first class seats. For sixty paise, we would get front row seats,” he recalled. This was also when he started attending Hindustani classical concerts at St Xavier’s with his parents, and finally fell in mohabbat with Marathi. “It’s been more than 40 years, but I still try and go every year,” Mehta said. He also tried to learn classical music, and for a be-taal, someone who could not keep beat, he did reasonably well. “My brother Parag, who heard my riyaaz and learnt, continues to sing very well though,” he said.

His idea of being a singer was “wearing a kurta like Amjad Ali Khan and singing like Pandit Jasraj”. He learnt under Ustad Ghulam Mustafa Khan sahab and considers his sons Murtuza Mustafa, Qadir Mustafa, Rabbani Mustafa and Hasan Mustafa his brothers. He learnt for a bit under Pandit Vinayak Rai Nanalal Vora, whose son Neeraj Vora (the late actor and director) would handle classes. “He would single me out for my bad taal, and make me sing songs in Gujarati. I would forget the lyrics,” he recalled.

Years later, when he lived opposite Prithvi theatre, in a house whose landlord was Shashi Kapoor, Mehta watched his first play, in which Naseeruddin Shah played Oedipus. “I was mesmerised and affected by his performance. I became a theatre addict.” There,new links were forged, with Benjamin Gilani, Tom Alter and the like. “It was not a theatre scene as vibrant as Delhi, but it was there,” he said.

What does Mehta do in his spare time? Does he read? Oh yes, but cookbooks. “I have bookshelves full of cookbooks. When I cook, the sur and taal sit very well. Amjad Khan’s son Shadaab Khan gifted me this book by Mirza Jafar Hussain, who translated old recipes from Persian. These are written as stories. The measures are in seer and tola. I read those stories and try to find recipes of korma and nihari.”

Speaking of his bond with Vishal and Rekha Bhardwaj, Mehta recalled how he would drive Rekha around during her pregnancy. “I had a rundown Gypsy and I had a mic and stereo set too. When Vishal would want a demo for a director, I’d take singer KK along, Vishal would do the harmonium and Hitesh Sonik and rhythm programmer Bharat would join us,” he recalled.

And then, Mehta went about making his first short film, starring Shefali. I did not know direction, but everyone told me it was poetic. Zee, for whom I had made Khaana Khazana, asked me to do something for them. I went to Vishal, who directed me to a writer in Delhi, who sent me 10-12 stories. I ended up liking one that was written by Vishal himself. We did not know anything about screenplay, and went and asked Gulzar saab about it. We got scolded, but he also gave us tips. I cast Shefali again in Highway, and chose Ashish. I often saw a boy waiting for Ashish on the bike, and realised that it was Manoj, who was very very angry those days with the world. He was fresh from Bandit Queen, and I had rejected him for Highway. But, when I met him in person, I saw genuineness, and there was mutual love!”

Speaking of his early work, Mehta said Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar was a dark comedy that explored the migrant issue, but was not really understood then. “I later spoke about it again in Citylights.”

In Aligarh, which won Bajpayee plaudits, Mehta said that the picturisation of Madan Mohan’s immortal song, ‘Aap ke nazron’ on Bajpayee “is my love for him on film, an ode to our friendship”. “The music company wanted a lot of money for the rights to use two songs by Madan Mohan in the film, and it was way off our budget. But no other song would have given the film that bhaav (emotion), and so I decided to pay the bhaav (cost),” he smiled.

In many ways, Mehta has made films that serve as cautionary tales for society. It’s a different matter than those warnings were ignored then. “I gave you a warning. Shahid reflects the current state we are in now. Citylights touched upon the plight of migrant workers, which we later saw during lockdown. Aligarh was made when Article 377 was in force. I wish to be a chronicler of our times through stories of the common man,” said Mehta.

Helping him take those stories to the audience now is actor Rajkummar Rao, with whom his seventh collaboration is the rural sports drama Chhalaang, which will release soon on Amazon Prime Video. “After Manoj, I think Raj is my muse. There’s honesty in his face,” said Mehta, narrating how the producer of Shahid finally agreed to Rajkummar’s casting after watching a night show of Ragini MMS. “He said we might not make money, but this boy is good,” said Mehta.

As for Chhalaang, which was shot in Haryana, Mehta said that for a change, unlike his previous films, where Rajkummar either goes to prison or dies, he lives a free man in this. The film is also his first Diwali release. “During the pandemic, and its aftermath, I’ve had two releases [Omerta and Scam 1992] and a third is due for release. This is my seventh film with Raj in as many years. And, I’ve told him that come what may, he has to make a movie with me every year,” smiled Mehta.

Watch Also: