India’s new National Education Policy: Welcomed, but not without apprehensions

India’s New Education Policy, coming after a gap of 34 years, has been widely welcomed by experts and academicians but, not without certain apprehensions.

On July 29, 2020, Wednesday, the Union Cabinet cleared a new National Education Policy (NEP), one that proposed drastic changes in school and higher education. Union Education Minister Ramesh Pokhriyal ‘Nishank’, while announcing the NEP, described it as the beginning of a new era in the field of education and said it will be uniformly implemented across all Indian schools keeping ‘diversity’ in mind.

The new education policy has come after a long gap of 34 years; India has been following the National Education Policy, 1986 until now. In 2016, the Narendra Modi-led NDA government at the centre shifted gears to bring in the new education policy. The government constituted a nine-member committee, headed by K Kasturirangan, a senior educationist and former Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) Chancellor. The Centre sought suggestions from the public once the Kasturirangan Committee submitted a draft for the new education policy.

Pokhriyal said the draft received suggestions from millions of people, including students, parents, teachers, educationists, experts, former education ministers and leaders of political parties. MPs, the Standing Committee of Parliament, and many people across political parties were also consulted in this regard. Then, NEP of about 66 pages in English, and 117 pages in Hindi, was approved.

Here are some of the major changes proposed in the NEP:

School Education

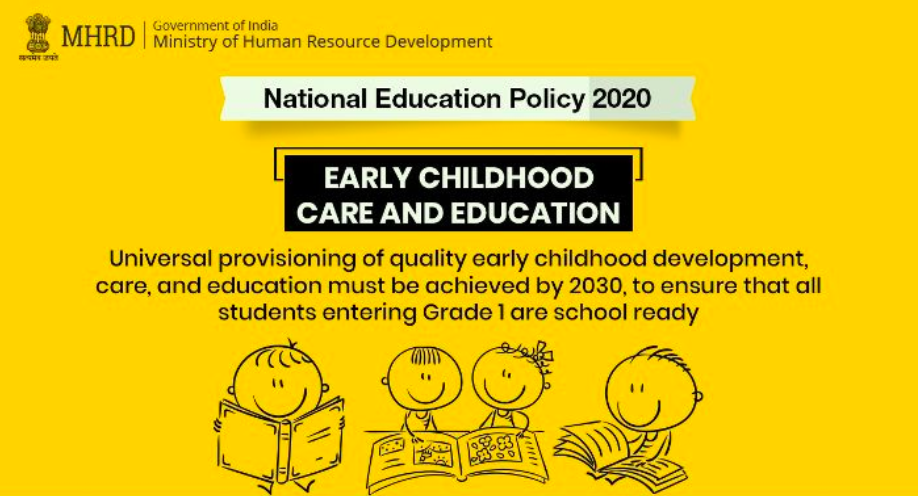

The new education policy believes Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) to have a strong impact on the development of children in the future and has, therefore, included it as a vital foundation.

The scope of Right to Education (RTE) has been widened. It was earlier for children from six to 14 years of age. Now, it has been expanded to include children from three to 18 years of age, making way for compulsory primary, secondary and senior secondary education. Anganwadi system for pre-schooling of young children is in place already, this structure will be strengthened.

Under early childhood policy, the first five years will be of early schooling. It means that children from three to six years of age are also brought under the school education. At present, children between the ages of three to five years are not included in the school education system and the children of five or six years are admitted to class one or enter the primary classes.

A major shift in the basic pattern of school education – from the current system based on 10+2 to a 5 + 3 + 3 + 4 system – has been proposed. Under the new 5 + 3 + 3 + 4 pattern, the first five years of education will be undertaken in pre-school and classes I and II together with five years. At the age of eight to 11 years, the next three classes will be classes III, IV and V. This will be followed by classes VI, VII and VIII at the age of 11 to 14 years and classes IX to XII at the age of 14 to 18 years. The studies for classes IX to XII will be board-based, NEP has simplified it to a great extent.

The government has also set a target of 100 per cent gross enrolment ratio (GER) in school education by 2030 and 50 per cent in higher education. According to a survey conducted by the All India Survey on Higher Education, India’s higher education GER in 2017-18 was 27.4 per cent, targeted to be doubled in the coming 15 years.

Anita Karwal, principal secretary of the department of school education in the Education Ministry informed that it has also been proposed to bifurcate the board examinations wherein the board examinations may be held biannually. This will reduce the burden of studies for examination on children and they will be encouraged to focus on learning and assessment instead of rote memorisation.

Use of mother tongue

As per the new education policy, children will now receive instruction in classes I to V, and possibly up to class VIII, in their mother tongue. It has also been recommended for further classes. The Education Ministry stated that children understand things better in its mother tongue, so early education should be in the medium of its mother tongue. This has become a majorly-contested move.

Anita Rampal, former head and dean of the faculty of education at the University of Delhi, noted that almost every education policy reform called for mother tongue being the medium of instruction in primary education but it was never fully implemented.

However, many are questioning the feasibility of this move citing that when children move to higher classes, the medium of instruction will change to English, they will find it hard to cope. The other concern is whether adequate teaching material is available in local languages.

On this, Anita Rampal told Gaon Connection, over the phone, that the government will have to ensure adequate, quality teaching material in local languages. She noted that governments in the past have also paid lip service to children being instructed in their mother tongue but, had not done enough in this direction.

Senior journalist Urmilesh supported primary education in mother tongue but, argued that the governments will have to ensure its implementation in both the government primary schools as well as ‘elite schools’ in the bigger cities. He called for revoking English as the medium of schooling in private schools because he believed it to be a sheer injustice to the poor, Dalits, and other backward and oppressed sections of the country.

The new education policy also emphasised on children completing the first phase of education, that is, up to Class XII, having at least one skill that can be used to earn a livelihood. The government said that internships will be provided in all schools and children will be able to go to local establishments and learn any skill of their choice.

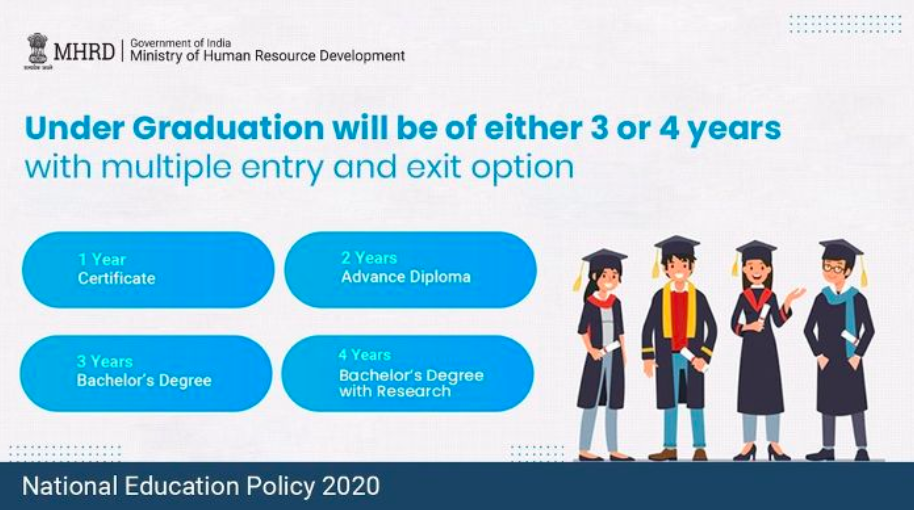

A flexible higher education system

The NEP called for a flexible higher education system, the most prominent feature of which is a multiple entry-exit system. For instance, if a student completes only one year of a course, a certificate will be given, those completing two years of higher education will be given a diploma, and graduation degrees would be awarded to those who complete three years.

Amit Khare, secretary of Higher Education informed that a student wishing to work after graduation can opt for a three-year course. Students who wish to pursue higher education and research will take the fourth-year course. With this, the present three-year graduation course will be expanded to four years. MA will now be only a one-year course while the students opting for research will be able to do PhD directly, without doing the two-year M Phil course.

The MPhil course is currently limited to the central universities, while in most state universities, students, after MA, are eligible to sit directly for PhD entrance exams. In many central universities too, students enter PhD directly after qualifying NET. Gaon Connection spoke to a number of students who questioned the rationale behind the MPhil course.

However, Rohit Datta Roy, an MPhil holder from JNU and currently pursuing a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge, does not agree. Rohit, a resident of Kolkata, told Gaon Connection over the phone that MPhil course has its own significance and it cannot be ruled out. “The government, by eliminating it (MPhil course), is moving towards the American education system, where education is a commodity and business,” he rued.

“PhD in the American system takes a minimum of seven years old because a person can take admission in PhD directly after four years of graduation. India is also moving along the same path,” he said. “Doing away with MPhil and making MA optional and reducing its duration would seriously affect the quality of research because it is only through these courses that people prepare themselves for the research activity,” added Rohit.

“While the government is talking about multi-entry-exit in graduation, it is actually going to prolong the PhD process. It will not be possible for any student in Indian context to pursue a seven-year PhD. It will actually be a waste of time and resources,” concluded Rohit, pointing out that Europeian universities chose to not adopt the American system due to this reason.

Multi-disciplinary Education

The new education policy talked about multi-disciplinary education, that is, a student may choose science as well as subjects of humanities and social sciences in classes X-XII and for graduation. One stream would be a major and another will be a minor under this system.

Khare stated there are many students who wish to take up music or arts besides science subjects and such a system would be very beneficial for them. Besides, various educational institutions will also be multi-disciplinary, which means that IITs and IIMs can also offer subjects other than engineering and management. Many argued against this move.

Graded autonomy

As per the new education policy, under graded autonomy, the burden on the universities would be reduced and the colleges would be provided academic, administrative, and economic autonomy. Many teachers and academic experts, however, are opposing this move.

Under graded autonomy, an administrative unit or the board of governors would be instituted in every higher educational institution and it would have academic, administrative, and economic powers. The teachers’ unions of Delhi University (DU) and JNU have opposed this board system. They allege that the government wants to clamp down on higher educational institutions in the name of autonomy through the board of governors.

“The government, through the board of governors, seeks control over the fixation of fees, salaries and appointments of teachers, courses and other academic programmes in higher educational institutions, which is a hoax and deception in the name of autonomy,” Laxman Yadav, an assistant professor at Zakir Hussain College, DU, told Gaon Connection.

Quality in higher education

The NEP conveyed the government’s commitment to spare no expense to promote quality in higher education. The government talked about spending six per cent of the GDP on education in NEP. NEP also discusses fee fixation and capping (limiting).

To further centralise higher education, institutions like University Grants Commission (UGC), All India Council for Trade Education (AICTE) and National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE) will be brought under one institution and there will be only one regulatory body for higher education with the exception of medical and law educational institutions. In addition, the National Research Foundation has also been set up to promote research. To promote uniformity in higher education, central, state and deemed universities will be reviewed on the basis of the same standard. NEP has also asked to conduct a common entrance test for the entire country.

To promote the quality of education, NEP directed that posts like shikshamitra, ad-hoc, guest teacher, etc. be gradually abolished and regular and permanent teachers to be appointed in both school and higher education by constituting a better selection process.

About this, Dr Laxman Yadav informed Gaon Connection that the appointment process in educational institutions has already been stalled, and by further eliminating the system of ad-hoc and guest teachers, the government wants to appoint teachers on a contractual basis, who will get paid on per class basis only, devoid of any social security like insurance, leave, pension, etc. As per him, the government appointing the regular teachers would have been a positive step but, in his tenure so far, no such indication was provided by the government.

Datta pointed out that Modi government had consistently shrunk the education budget and at present, it is even below four per cent of the GDP. How then can the present government be relied upon, he wondered.

Rampal said it would have been good had the government reviewed the older education policies in this one and seen what was accomplished, what is implemented, and what is still untouched. But the review of the old education policies has been hastily done in one paragraph and some old and some new announcements have been made.

“It remains to be seen, how much the governments will be able to actualise it. I say ‘governments’ because school education is a state subject and the Centre will also have to coordinate with the state governments to make this education policy a success,” she said.

Former UGC member Yogendra Yadav seemed pretty satisfied with the new education policy. He said it was feared of the present government to promote saffronisation and privatisation in the new education policy, but none of it was seen in the seventy-page document. “The right to education, which was earlier for six to 14 years, has now been for three to 18 years, it is a welcome step. Besides, the early childhood policy is noteworthy for it would bring children of three to five years of age, the actual age when the learning begins, under the purview of government care,” he said in a Facebook live.

He, however, harboured certain apprehensions about the NEP. He questioned whether the government will be able to accord that much importance to education to spend six per cent of the GDP on it. Moreover, NEP did not address the problem of rampant privatisation of education from school education to higher education. He sought the government’s plans to save the public education system and to ensure uniform education to all, especially higher education, which is becoming increasingly costly even in government educational institutions. Finally, he questioned whether NEP will be able to be implemented in full.

Ambreesh Rai, convener of the Right to Education Forum (RTE Forum) found NEP to be largely acceptable but lacking the clarity as to how and in which direction RTE would be expanded. “RTE has been expanded from six to 18 years but is still not made legally binding. That is why, after RTE, the enrolment rate in education may have increased but, the drop out rate has not gone down effectively. Had the NEP addressed these issues, it would have been better,” he said.